Mars Rover Work Spawns PDF Collaboration Software

NASA Technology

Like satellites in orbit, some spinoffs just keep spinning.

Alliance Spacesystems, founded by a handful of engineers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in 1997, has become a major supplier of satellite flight hardware and other high-tech composite structures. But a tool the company’s engineers designed just to make their own lives easier has successfully spun off into a completely different line of work.

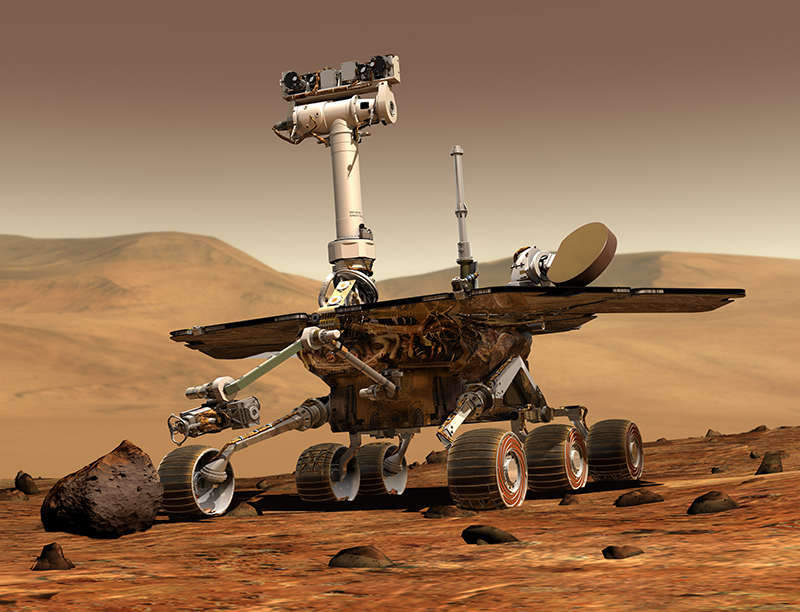

Among Alliance’s first projects were the robotic arms for NASA’s twin Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity. The company, which had fewer than 20 employees at the time, had two years to design, build, and deliver the arms.

“Having engineers coming from JPL who are all very bright and talented, when they’re under a lot of pressure, they get creative,” says Richard Lee, CEO of Bluebeam Software, the company that arose from that creativity.

Alliance wanted to become more efficient in mundane tasks like reviewing, marking up, and circulating documents and drawings, as well as converting information from computer-aided design (CAD) software like AutoCAD into PDF format. This would free up more time for actual engineering.

“We were significantly challenged as a small team trying to get a large amount of work done in a short time,” says Brett Lindenfeld, the former JPL mechanical engineer who was Alliance’s project director for the robotic arms. “We just didn’t have the months to do it and didn’t have the people—that’s the bottom line.”

Lindenfeld is now vice president of operations for Motiv Space Systems, yet another company that spun off from Alliance.

Adobe Reader was already popular in those days, but no one had developed a PDF program to meet engineers’ needs, he says. “We just weren’t happy with the way we had to create those PDFs or the way they came out.” As computer-automated machining became more popular, the machine shops making the parts Alliance designed wanted three-dimensional CAD models, as well as two-dimensional drawings. But these were often degraded when they were converted from one program to another, resulting in models and drawings that didn’t quite match.

So Lindenfeld and some of the company’s other engineers built technology that would later lay the foundation for Bluebeam’s first product, Pushbutton PDF. With the click of a button, the plug-in would convert CAD models into high-resolution, scalable drawings. The evolution of the software has brought enhancements such as the ability to view, manage, and mark up rotatable, three-dimensional models while including data describing parts and materials, any other relevant properties, and hyperlinks for easy document navigation.

“Basically, that PDF is embedding all your data, and you don’t have to worry about it getting separated or lost between the two,” Lindenfeld says.

The creators saw opportunity in what appeared to be a neglected market.

“We were focused on ourselves as engineers, but it looked like there were other markets that could use this,” Lindenfeld says. Lee, a friend, was brought on board to help turn what had begun as a way to meet a NASA product delivery deadline into a product in its own right.

Technology Transfer

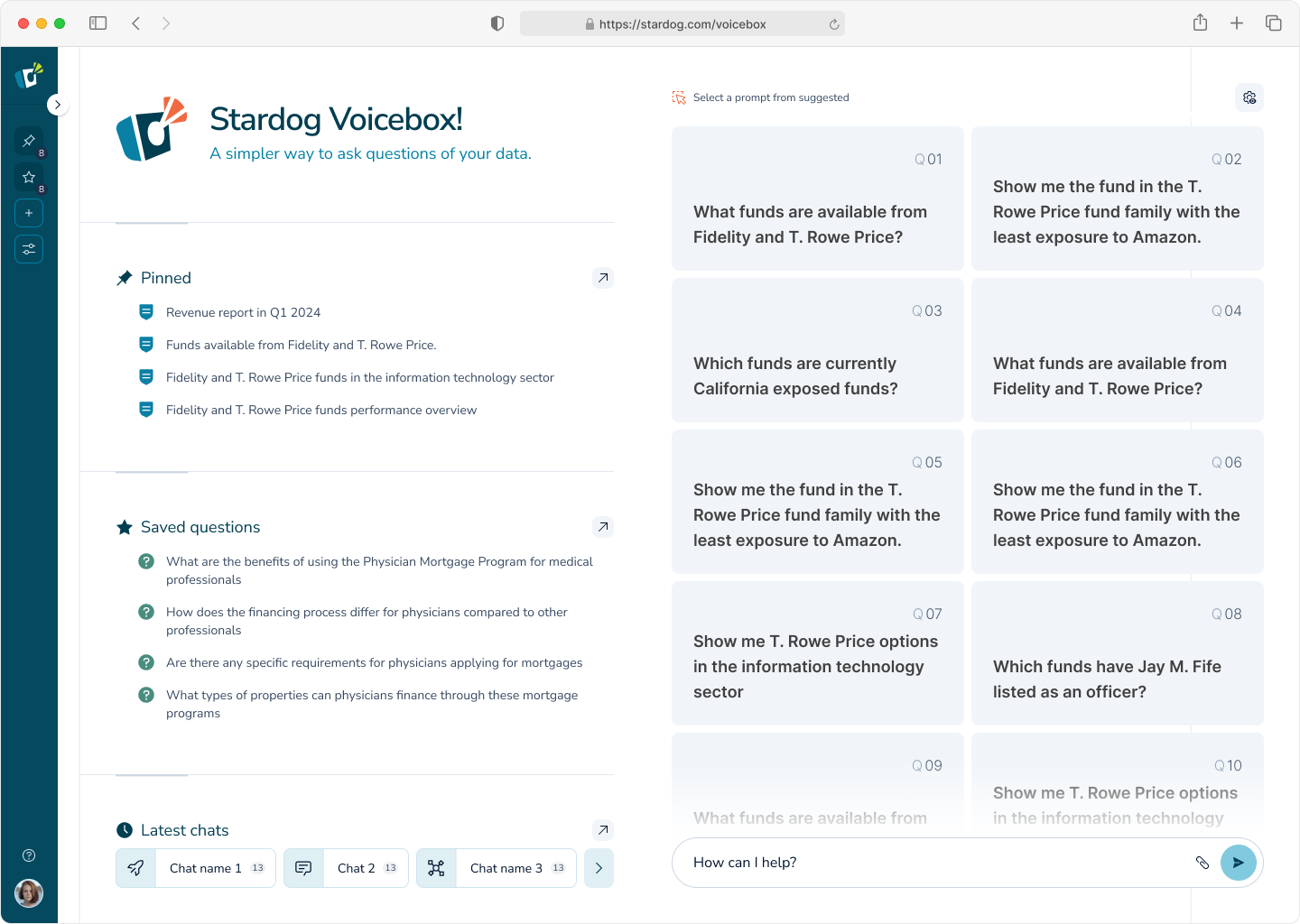

Bluebeam Software Inc. was founded in 2002 and cultivated a customer base not just in engineering but also in industries like architecture, construction, and oil and gas. Pushbutton PDF was followed by Revu, an application focused on the technical review process. Revu allows and tracks symbol-based document markups from multiple parties simultaneously or separately. This allows real-time collaboration between the field and the office, or among multiple offices around the world.

“In the construction business, for example, you have literally hundreds of people running around with iPads and adding comments to drawings,” Lee says.

Bluebeam’s current primary offering, Revu also includes other tools for PDF creation and markup, as well as project management, in one cloud-supported application. Its most advanced edition, eXtreme, allows users to include features like batch processing, PDF form creation, and redaction among other functions. Bluebeam Vu, meanwhile, is a high-speed PDF viewer that the company offers for free download.

Bluebeam Q automates PDF production from source files, bFX is a protocol that allows integration of Revu with document and data management systems as well as third-party software, and Studio Enterprise allows collaboration behind a firewall in a locally hosted environment.

Lee says the company’s largest client base remains in fields where AutoCAD is dominant, but it has also found a place in government and business, where the software reduces paper waste and increases efficiency.

Benefits

Bluebeam has steadily grown by about 50 percent every year, and in October 2014, German software provider Nemetscheck bought the company for an even $100 million. By then, Bluebeam claimed more than 650,000 users in 96 countries, and it employed about 150 people in four office locations. By the company’s numbers, Revu was used by 58 percent of the top international design firms, 64 percent of the top American design firms, and 74 percent of the top American contractors by revenue.

Lee says the 11-year span that the company’s chief technology officer, Don Jacob, spent at JPL helps to inform the software and keep it relevant to the space industry and engineering in general, and JPL is also among Bluebeam’s clients.

There, a group known as the A-Team has found an alternate use for the software. The A-Team is an ad hoc group of specialists from different backgrounds that holds sessions for brainstorming or feasibility studies to address NASA’s priorities. It’s actually a different group with each iteration, depending on the topic at hand. Around mid-2013, systems engineer and space architect Raul Polit-Casillas, an A-Team core member, and A-Team lead John Ziemer were tasked to come up with a better way to facilitate these discussions. Polit-Casillas had seen Revu advertised in a magazine, and it wasn’t until much later that he learned of the software’s NASA origins.

Rather than use Revu to allow collaboration by parties in multiple locations, the A-Team primarily uses it like a sort of endless whiteboard to facilitate meetings. “Bluebeam was not meant to do this, but it’s worked very well, to have many people working on a document in a collaborative way,” Polit-Casillas says. From their tablets, participants can add text, tags, images, links, diagrams, and other material for all to see, and each can flip back or forward through the material. Actual electronic whiteboards and other devices can also be tied in. The team calls this approach “A-Language.”

“With all those things together, it’s kind of like a living document,” Polit-Casillas says.

Lindenfeld says aerospace, where the software originated, is a natural birthplace for such innovation, as it’s a field that constantly requires creativity to overcome complex engineering challenges. He is especially pleased that the software he helped to pioneer has also become a major tool for the construction and architecture industries.

“It’s really neat to see industries that have historically not been able to immediately capitalize on available technology being propelled forward by advancements from an industry that has to innovate,” Lindenfeld says. “I don’t think it was happenstance that this started with NASA work.”

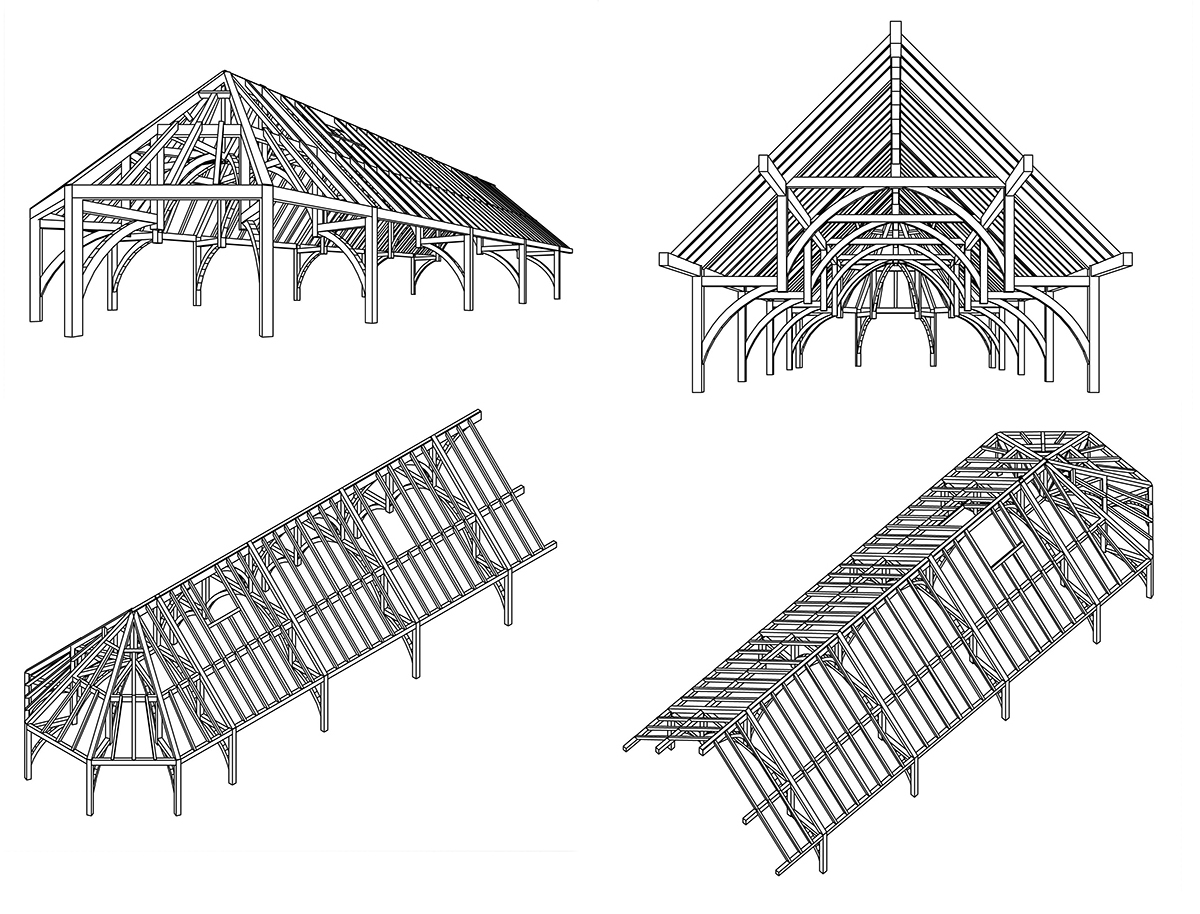

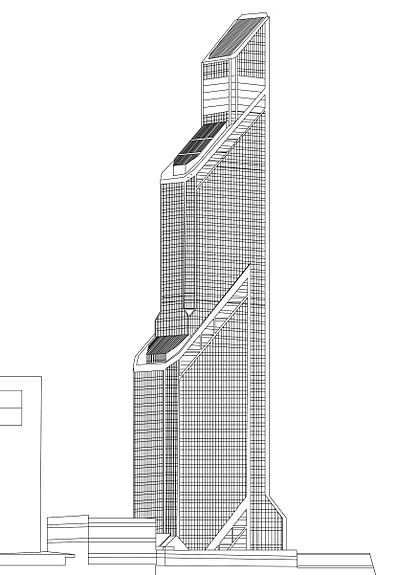

One of Bluebeam’s earliest and most important features is the capacity to convert three-dimensional computer-aided-design models into high-resolution, scalable PDF drawings.

Although Bluebeam was created to meet the needs of engineers, it has become popular in other industries, especially those that also use computer-aided design, such as architecture. This AutoCAD drawing depicts the Mercury City Tower in Moscow. Image courtesy of Edvard Wlodyga, CC BY-SA 3.0

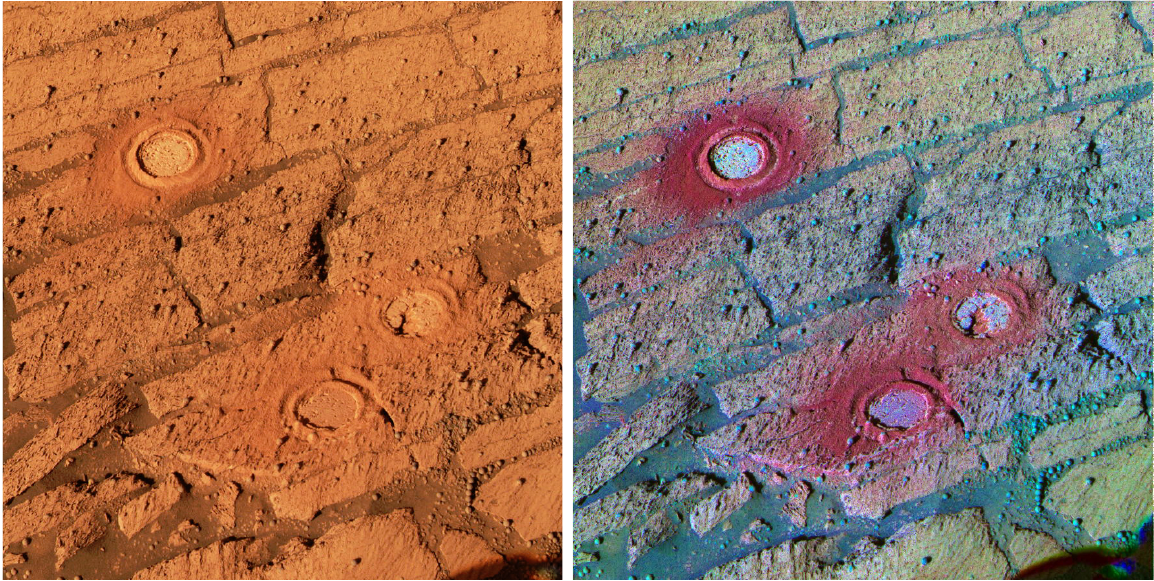

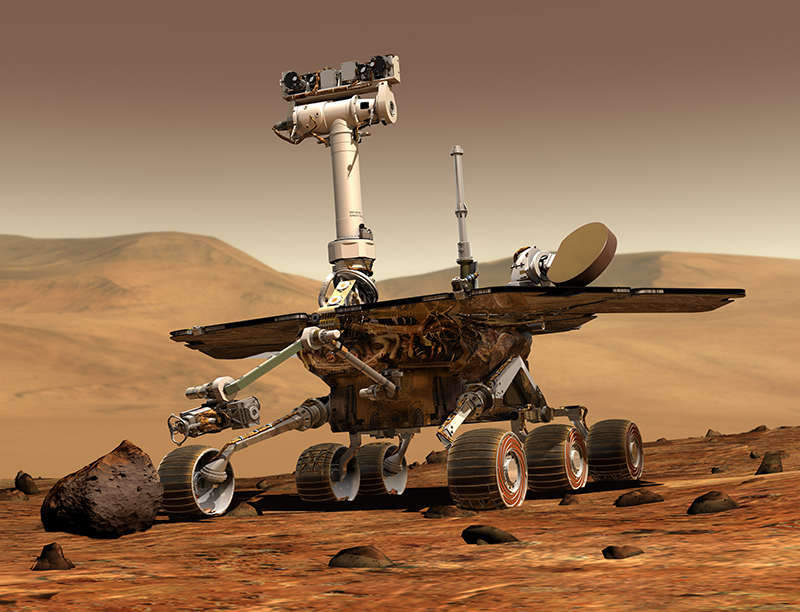

Former Jet Propulsion Laboratory Engineers at Alliance Spacesystems created the first Bluebeam software to help them meet tight deadlines for designing the robotic arm for the twin Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers in the late 1990s. The engineering-geared PDF reader soon spun off into its own company and popular product line.