Zinc-Silicate Coating Blocks Corrosion

NASA Technology

NASA needs materials that are strong and can hold up over time. Sometimes that means the Space Agency designs brand-new, high-tech materials—but sometimes it sticks to industry standards, like steel, and creates a game-changing coating to protect it from the elements.

The good news is that anyone else using that tried and true material can benefit from the new coating too.

That’s just what happened in the 1970s, when a team at Goddard Space Flight Center developed a mixture of zinc powder and potassium-silicate to protect metal surfaces from corrosion.

Zinc had long been used in anti-corrosion coatings, but NASA wanted something that was easier and more cost-effective, so Goddard chemist John Schutt began to play around with the formula. The product he ended up with did more than cover the metal to block sea spray, fog, or other corrosive elements. It actually chemically bonded with the underlying material.

In other words, explains Earl Ramlow, who started using the coating more than 20 years ago as an engineer working for a military contractor, once you apply the coating, “it becomes part of the parent steel.”

The result was an incredibly effective and durable treatment that didn’t even allow water damage or corrosion to seep into protected areas if the coating was scratched or incomplete.

NASA put the coating to use on structures at the seaside Kennedy Space Center, where it protects launch facilities not just from the salty, tropical environment but also from the temperature spikes and high-heat exhaust of rocket launches.

Technology Transfer

But the Space Agency wasn’t the only organization with structures to protect. The coating was soon put to use on a range of metal structures, from bridges to boats to the Statue of Liberty.

To sell the coating in the private sector, NASA had licensed its patent to a company called Inorganic Coatings (Spinoff 1984, 1985, and 1990).

But, explains Ramlow, before the company could produce the coating commercially, it had to perfect the manufacturing of one of the key ingredients, liquid potassium-silicate.

“NASA basically had the recipe on the proverbial napkin,” he says. “Even the patents describe the raw materials with very basic instructions.”

Inorganic Coatings turned for help to another company, Polyset, founded by two former GE chemical engineers. “So they sat down in the basement and tweaked the processing” until they consistently got good results, explains Ramlow. Polyset, based in Mechanicville, New York, then signed an agreement with Inorganic Coatings to provide them the liquid silicate exclusively for the NASA-derived coating.

But when Inorganic Coatings later tried to produce the silicate itself to save on costs, it was unsuccessful, and the faulty product it produced helped put the company out of business.

Ramlow experienced the problem firsthand in around 1989 or 1990, when he was working for a military contractor assigned to build causeways for the U.S. Navy, with Inorganic Coatings supplying the anti-corrosion coating. “Because Inorganic Coatings didn’t manufacture the silicate properly, when we applied the coating, it would look good, but as soon as we would put the causeway modules outside in dew or rain, it turned back into a liquid,” Ramlow says.

Later, other companies began making the coating, using liquid silicate manufactured by Polyset. But then history repeated itself, and once again Ramlow was stuck with a faulty product.

In 2002, he was working on another project, building modular causeway systems for the U.S. Army. But the anti-corrosion coating that was delivered didn’t use the Polyset-made liquid silicate.

“It was déjà vu all over again. The coating was resolubolizing, turning back to liquid,” Ramlow says.

Although Ramlow was able to finish both projects successfully—ultimately by sourcing the coating to one made with Polyset’s liquid silicate—the ‘black eyes’ from incorrectly manufactured batches and advances in other coating technology saw the product start to fall out of use.

But the NASA formula, when manufactured correctly, is still the best product available to prevent corrosion of metals, Ramlow says, and Polyset was the one company that had the ability to produce the key ingredient consistently.

So in 2010, Polyset decided to take the coating directly to market under its own brand name: WB HRZS Single Coat System, where the acronym stands for water-based high-ratio zinc silicate. It created a new protective coatings division and, because of Ramlow’s history with the product, hired him to head it.

“This is a technology that was almost lost by the industry because of its history. It was buried. It was forgotten. Polyset has brought it back to life,” Ramlow says.

Benefits

One of Polyset’s first customers for the coating was Chevron Oil, which is using it to protect its offshore oil rigs.

Ramlow described the benefits to the company, saying a single coat will prevent problems even in the splash zone, which is highly susceptible to corrosion. The Chevron representative was skeptical, he recalls, but agreed to test a small patch on a rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

“He told me, ‘I’ll call you in a month or two, because it’s going to fail,’” Ramlow recounts. But 12 months later, he called with different news: the test area had remained pristine, even though the rest of the metal was corroding all around it.

“That’s a key benefit of this coating: if you’ve got an area of unprotected steel, or the coating is damaged somehow, it will never undercut or blister in the protected area, because the coating is chemically bonded to the steel.”

That chemical bond also adds another benefit: it allows the surface to be electrically conductive, which deters marine critters, like barnacles and mussels, from clinging to the surface, Ramlow says.

Another benefit is that, unlike many other inorganic coatings that must be applied in a single pass or sandblasted off to try again, WB HRZS can bond to itself, so if the first coat is not thick enough, it is simple to go back and fix. And although just a thin coat—Ramlow recommends six- to eight-thousandths of an inch—is required, there is no harm, he says, if some spots end up thicker, unlike with other inorganic zinc coatings that crack when over-applied.

And because it is water-based, it’s a lot safer and more environmentally friendly than coatings that include solvents or thinning agents.

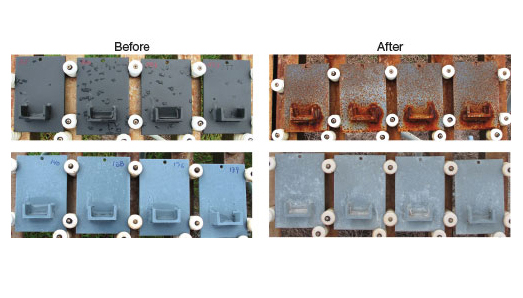

In fact, in a recent study at Kennedy of 21 coatings aimed at identifying environmentally friendly ones that meet NASA’s requirements for launch facilities, the Polyset product was one of just four to pass, says Kurt Kessel, who oversaw the testing. “It made it through all of the testing and it made it to the initial qualified products list,” he says. “It’s been initially accepted under the NASA specifications.”

Not a surprise, perhaps, considering the source of the formula, but Kessel said the testing was necessary since Polyset is a new manufacturer as far as NASA is concerned.

The company is working on expanding its customer base among companies that make ships’ hulls and interiors, as well as rail cars, hydroelectric plants, and bridges, and it is also going through the process to become an approved supplier for the departments of defense and transportation.

“Every year since 2010 we have doubled our revenues,” Ramlow says of Polyset’s coatings division, adding that when he makes his marketing pitch, he always invokes the NASA name, especially when he sees doubt about the performance of the coating. “I always tell people, remember where this product was born: NASA, a collection of the smartest engineers and scientists in the world, who work on spaceflight programs, where lives are at stake.”

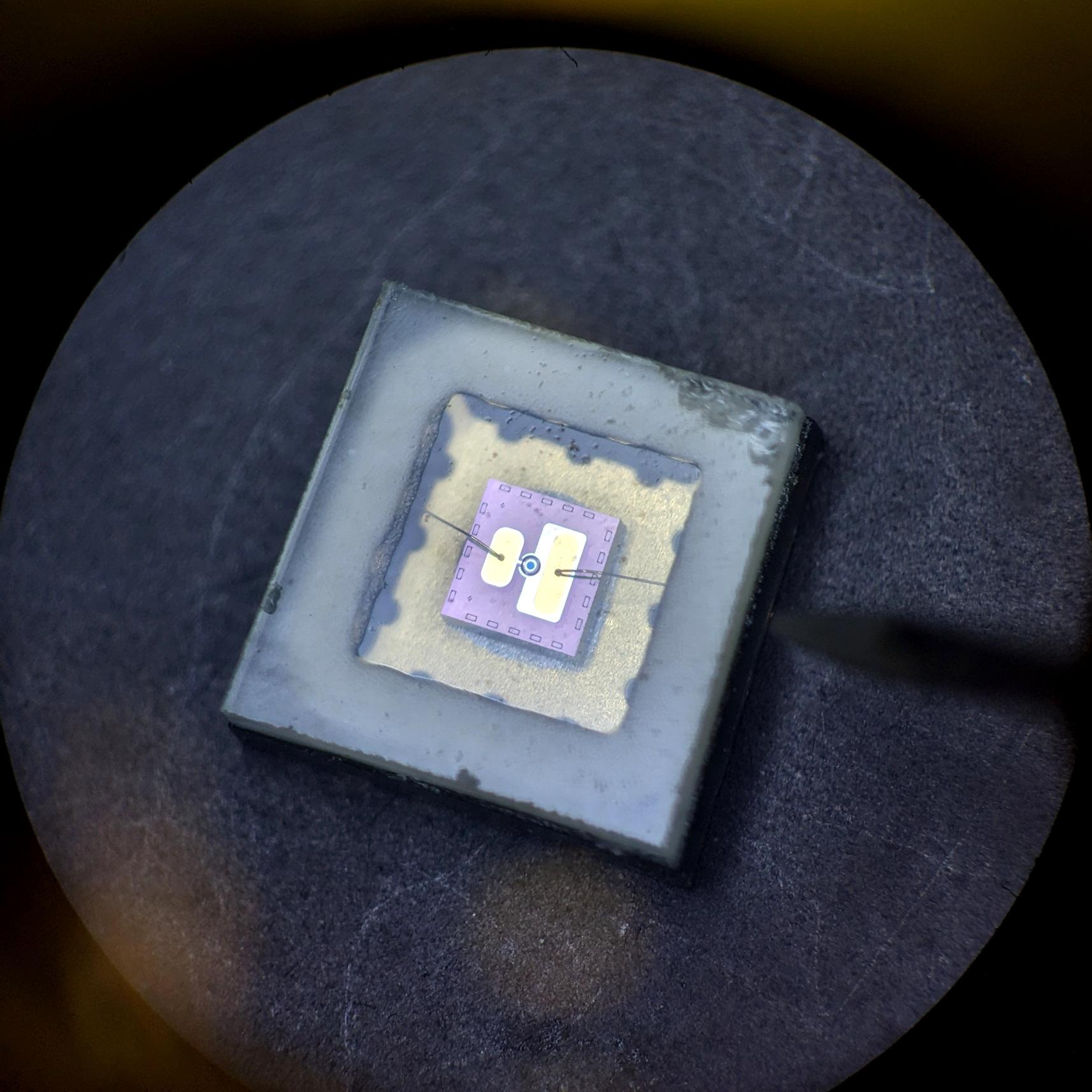

In a recent test at Kennedy Space Center, engineers applied environmentally friendly coatings to steel samples. After 18 months’ exposure in the salty sea air, the Polyset coated samples, bottom, remained nearly pristine, while the ones coated with another product, top, became riddled with rust and corrosion.

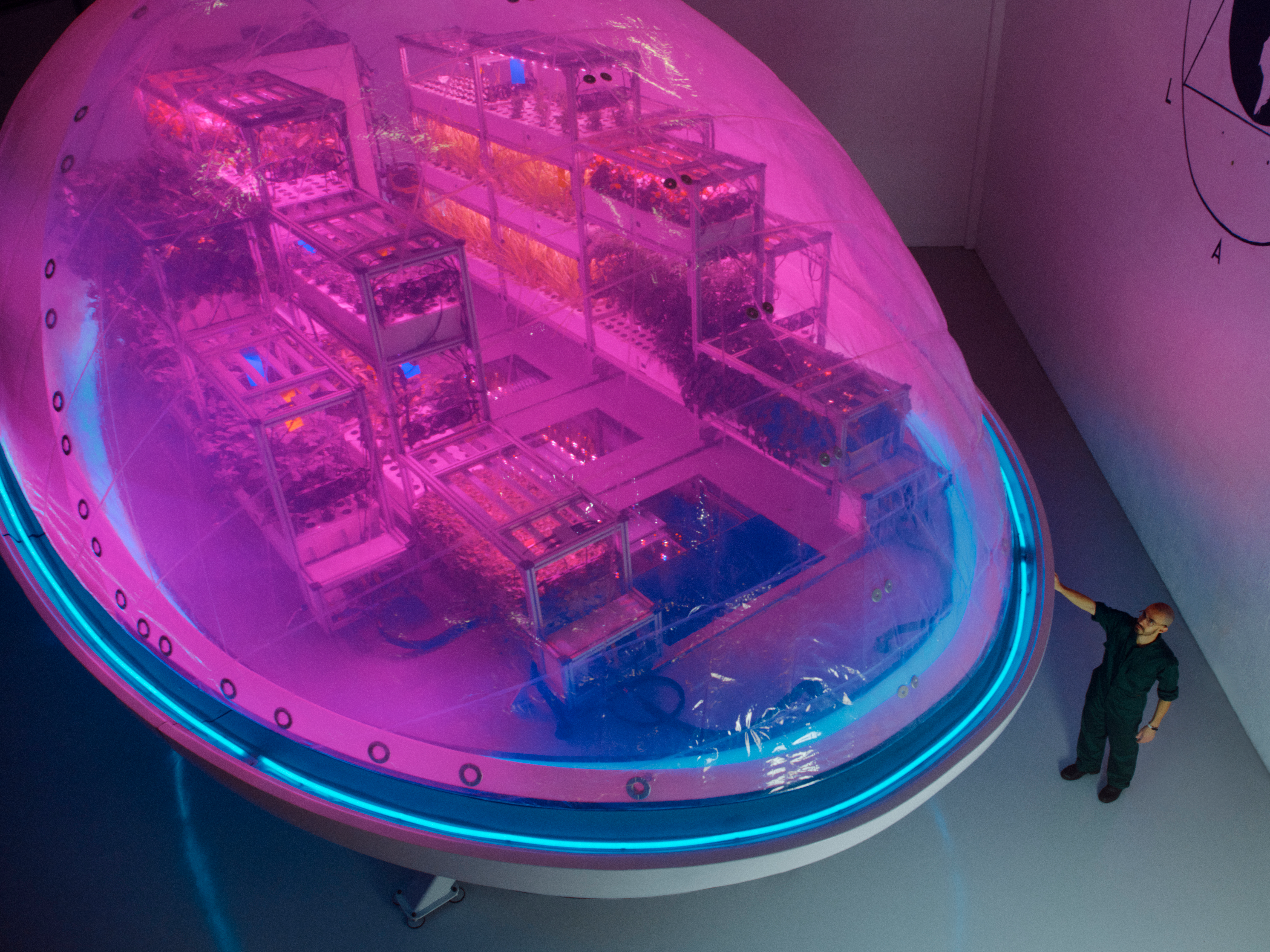

Polyset sells its coating to companies that operate offshore oil rigs like this one, which can suffer corrosion from the seawater. The company is also targeting ship and train builders, hydroelectric plants, and the departments of defense and transportation.