Now Anyone Can Make Electronics on Demand—Thanks to NASA Research

Chance Glenn traces the inspiration for his 3D electronics printer back to Star Trek, which he began watching in reruns in the late 1970s as a middle schooler.

He was struck by the replicator, a machine in the show that could produce food, clothing, ship parts, and anything else that was needed, on demand.

“Basically, you walk up to a replicator and tell it what you want, and it will make it for you,” Glenn recalls. “Years later, as an electrical engineer in the age of 3D printers, I began to ask myself the question: why couldn’t we do that with electronic devices?”

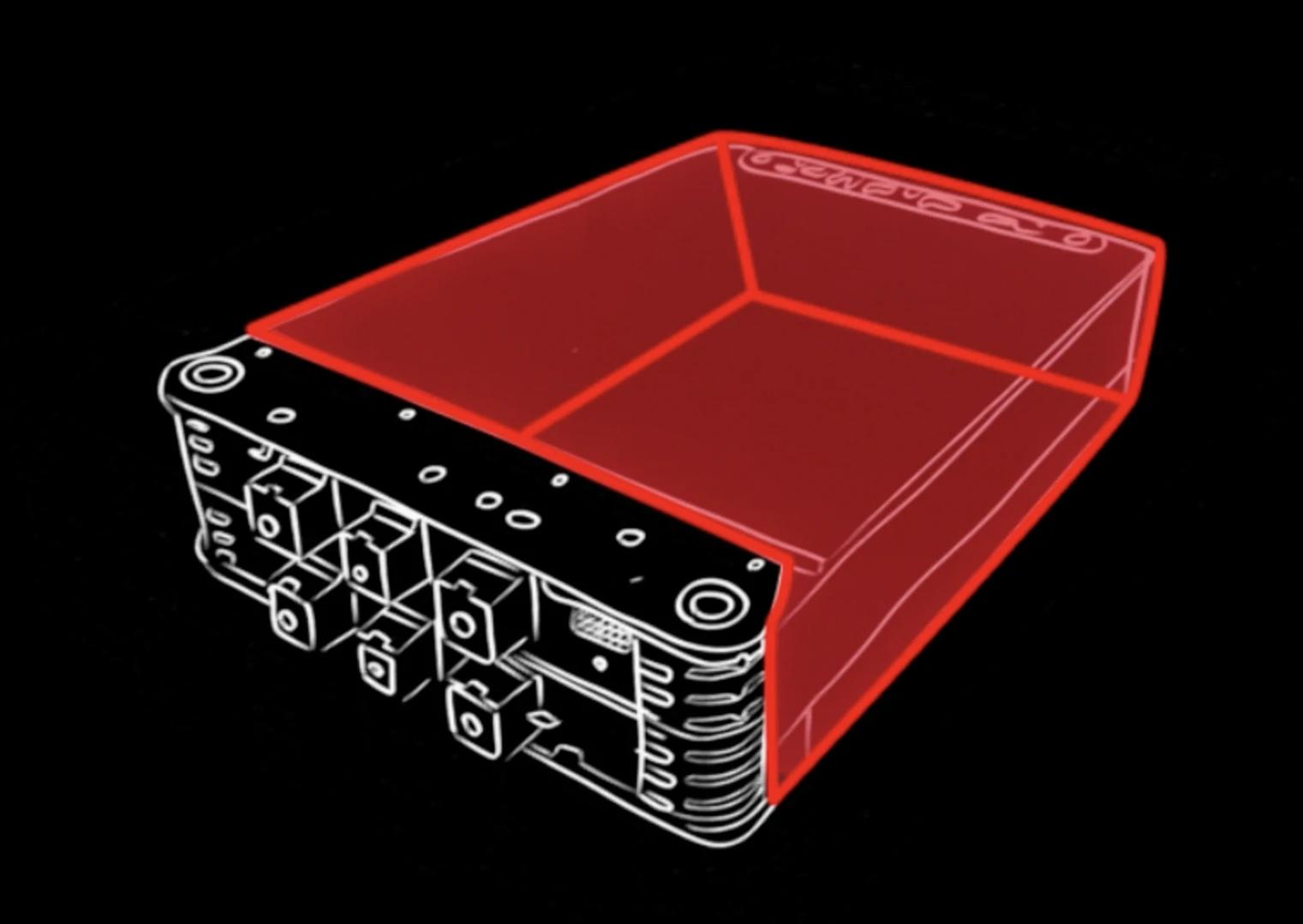

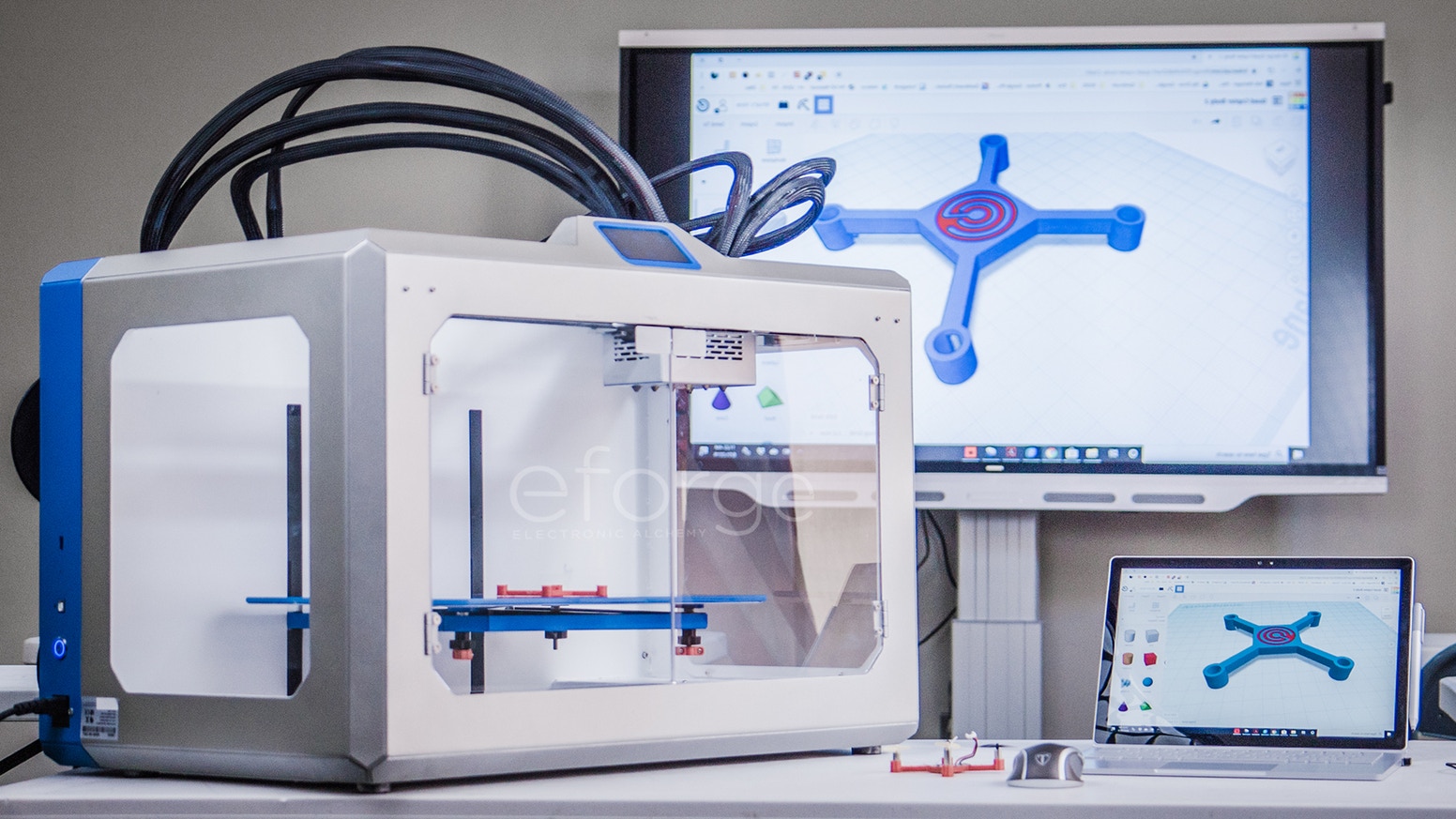

He started developing what would eventually become the Electronic Alchemy eForge, a 3D printer that enables anyone to manufacture their own electronics designs on demand. The machine can print sensors, lights, and other electronic components into shapes or onto fabrics or other materials. “It just broadens your ability to create new things and reimagine devices that we already have,” Glenn says.

Creating Electronics in Space

Glenn proposed the project to NASA’s Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) program, which funds research and development projects in technology areas that contribute to NASA’s missions. He was working with Alabama A&M University, where he was dean of the College of Engineering, Technology, and Physical Sciences.

The Space Agency selected Glenn’s project and supported it with about $1 million in Phase I and II STTR contracts. He also received a small Phase III Small Business Innovation Research contract.

Because the ability to 3D print parts in space could support long-duration missions, NASA has been working on the technology for years, with a more recent focus on electronics in particular, since these high precision parts and devices have failed in the past on the International Space Station.

“Currently the paradigm is that everything that’s used in space gets launched from Earth,” says Tracie Prater, a materials engineer on NASA’s In-Space Manufacturing Project at Marshall Space Flight Center. Prater helped with technical oversight of the eForge development.

“When you’re looking at analyses for long-duration missions—going to Mars or having a sustained deep-space habitat—the logistics requirements become, in some ways, prohibitive,” she says.

Being able to print parts or devices in space as needed could help reduce launch mass for a long mission by enabling the recycling of parts that have reached their end of life, Prater says. The capability could also enhance safety by helping crews respond to unexpected situations when there isn’t time to return to Earth or wait for a supply ship.

Six Basic Materials and a Machine to Print Them

To 3D print electronic devices, Glenn and the Electronic Alchemy team needed to develop printable materials with electronic properties and a 3D printer capable of printing multiple materials without manually changing the printer heads, which would be unwieldy. Electronic components typically require several materials, at least.

The eForge uses a fused disposition modeling 3D printing process, where materials are heated up to a liquid state, extruded through a nozzle like hot glue from a glue gun, positioned in space, and then allowed to cool and harden.

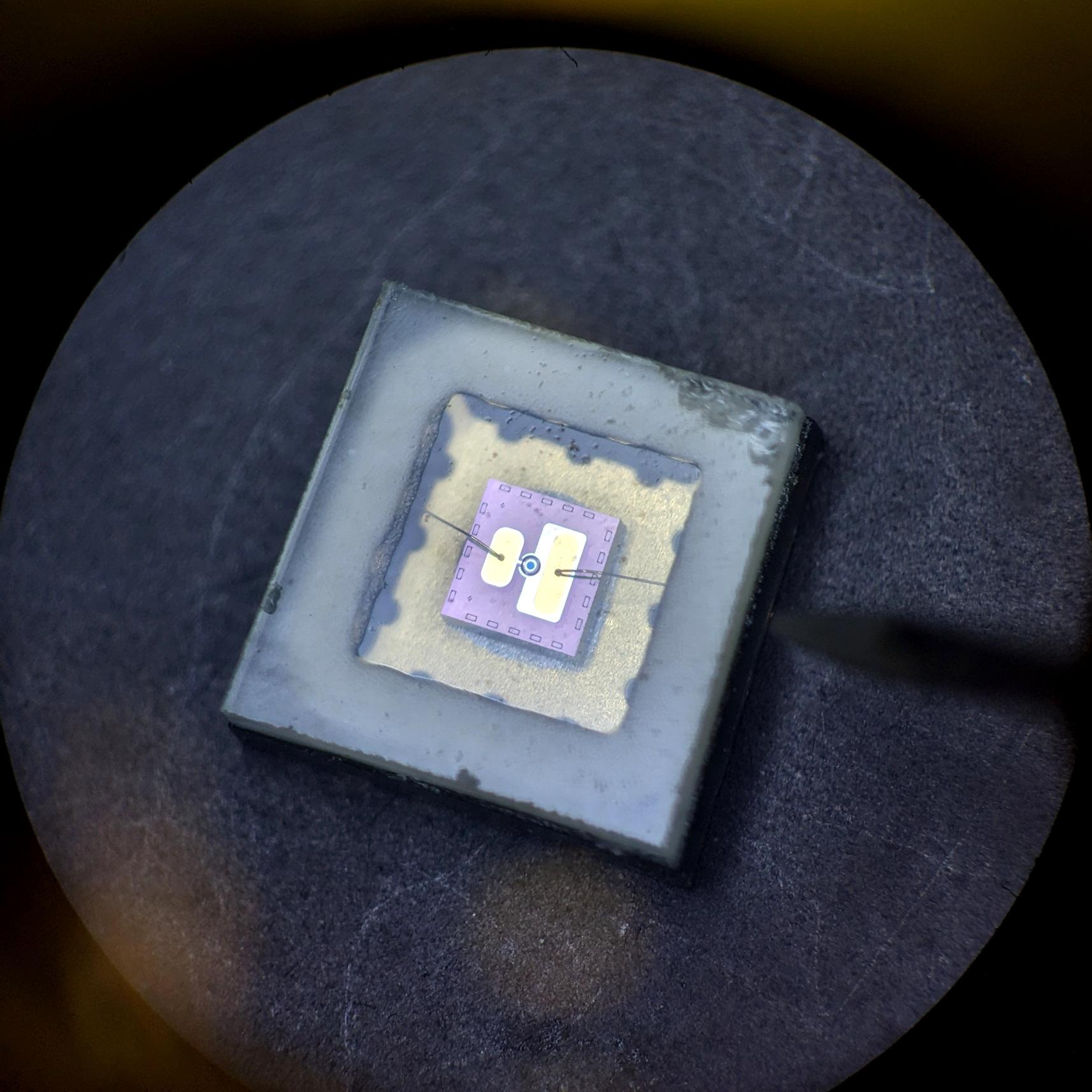

Glenn and his team developed and submitted for patents six basic materials for the initial iteration of the eForge printer, including conductive, insulative, resistive, and capacitive filaments, in addition to innovative semiconducting materials.

“They did the early research on development of these functional filaments for semiconducting devices,” says Curtis Hill, a senior materials engineer at Marshall who worked with the team to help verify and define the materials’ electronic properties.

The eForge semiconducting materials can be used in switches, communication equipment, and solar cells, or combined to create diodes and transistors for integrated circuits, computers, amplifiers, and more, according to the company.

Electronic Alchemy is continuing to develop new materials for the printer, Glenn says, including a filament that lights up with an electric current, magnetic materials, and a piezoelectric material that generates an electric charge in response to mechanical stress.

The initial eForge device has a single active arm that can pick up a filament cartridge, lay down the material, and then replace the cartridge and pick up another. This is done level by level. The first model will be able to print up to eight materials per layer—using filaments for building both electrical and mechanical components—and future iterations will allow for more than that.

Electronic Alchemy is working with Autodesk to adapt their layout tools, such as Fusion 360 and TinkerCAD, to the eForge. Users will design components within the eForge software or upload files created in other programs.

Creatives Meet Electronic Alchemy

Electronic Alchemy offered the first eForge devices for presale in October 2019 through a Kickstarter campaign that met its initial goal of $60,000 within three hours and raised more than double that by the end of the year. An engaged community is already active on Facebook and the Kickstarter page. The printers are expected to ship in late 2020.

Glenn hopes the machine will appeal to maker spaces at universities and schools. “Students are just learning how to make things,” he says, “so imagine putting something like this in their hands and letting them create circuits and devices that they have modeled and tested themselves.”

The device will also have a role in research and development settings, Glenn says. “You can design something, print it, test it, make sure it works, and if it doesn’t, you can redesign and reprint it, all within minutes,” he says.

The company plans to sponsor design competitions “to see who can make the best device,” he says. “It will create a library of devices that the next level of customers will be able to take advantage of.”

Glenn says NASA was essential to the Electronic Alchemy eForge. The agency not only funded the printer’s development, but also gave the project exposure and credibility, he says. And he continues to work with Hill on new material development.

“I can safely say that this would not be anywhere near where it is without NASA’s input,” he says.

Electronic Alchemy’s eForge 3D printer, developed with NASA funding, can print electronic devices on demand. Credit: Electronic Alchemy

NASA has been studying 3D printing in space for years because of its potential to make spaceflight safer and missions nimbler. Here, astronaut Barry Wilmore holds a ratchet wrench created with a 3D printer aboard the International Space Station in 2014. Credit: NASA