NASA Helps Bring Airport Communications into the Digital Age

Some of the best entertainment at the airport is all the action outside the window. Loaded luggage carriers zip past on their way to planes. Fuel trucks come and go. Catering trucks restock galleys. During winter, de-icing crews and snowplows add to the bustle.

This organized chaos is overseen by the ground-control managers as part of an airport-wide effort to ensure the safety of all ground operations. And as air travel has increased, the challenge of keeping track of all the moving parts has only grown.

However, a digital, wireless airport communications system developed in part by NASA is now poised to change the game.

For decades, airports have relied mainly on voice communications over unsecured radio frequencies, with landline phone calls as the only secure backup option. Going forward, the Aeronautical Mobile Aircraft Communication System (AeroMACS) will allow Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) staff in control towers to send safety-critical information digitally and securely – and should lead to shorter wait times on the tarmac.

Breaking the Language Barrier

Just how far airport technology had fallen behind became too obvious to ignore when consumer cellular service became widely available.

Passengers on the tarmac have high-speed data connections on their phones, “but the bandwidth available to a pilot on the flight deck for communications is under kilobits per second,” said Declan Byrne, president of the Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access (WiMAX) Forum.

The forum, an independent industry group established to support and advocate for the adoption of AeroMACS technology, also certifies the new hardware created for airports. The FAA and other air traffic-control authorities around the world, along with NASA, participate in the forum.

AeroMACS will eventually phase out the use of voice communication as the primary method of information sharing for airport ground operations. The new, encrypted, high-speed digital data networks will streamline communications among ground crews and air traffic controllers. Messages sent to a pilot after the plane is on the ground can include diagrams and GPS-style maps, as well as text instructions for runway navigation, gate assignment details, and surface navigation directions.

When any airplane lands now, the pilot gets on a voice network and talks to the air traffic-control manager over a radio. “If you've got a German pilot trying to speak English to a Chinese air traffic controller, the possibility of miscommunication certainly exists,” said Byrne, adding that a bad connection can compound the problem.

Aviation authorities from more than 150 countries chose and agreed to adopt the WiMAX standard. Formally adopted in 2007, WiMAX uses cellular network infrastructure that’s customizable for the new frequency – the spectrum of 5091 to 5150 megahertz is reserved for safety-critical aviation communications only.

A New Hardware Toolkit

NASA engineers have been part of this process from the start. The agency’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland took the lead on AeroMACS testing. The center had worked on these issues previously and had extensive expertise, which made it a natural partner for the FAA. The two organizations signed a Space Act Agreement in 2007 to validate the new system and establish functional standards.

“NASA was one of the leading technology R&D agencies that validated AeroMACS,” said Byrne. “The agency deployed a system and tested it. That work was essential for stakeholders in the international aviation community. It proved that this was a reliable standard they could support.” To run the first aviation tests, NASA worked with the Broadband Wireless Access division of Alvarion Technologies Ltd. to modify existing WiMAX hardware. Acquired by Telrad Networks, the company was able to leverage its work with the agency to become one of the first to receive AeroMACS Wave 1 Certification, an independent validation of performance from an industry observer.

In this family of hardware, any sensors called subscriber stations will collect, transmit, and receive data. Telrad builds the base station which performs the same function as in a cellular network, routing transmissions, with GPS providing timing for the network. The company also assists with identifying the best antenna type, and placement depends on the airport configuration and signal coverage needed around the surface.

A proxy client server executes banking-level security protocols and enables user authentication to verify the sender and receiver, blocking outside intrusions. The Access Service Network gateway enables connectivity throughout the network. This complete system customized by Telrad is all that’s needed to set up an AeroMACS-based wireless network.

“Airports have a dedicated frequency allocated by government regulators that is free of charge for them to use,” said Yishai Amsterdamer, general manager of Telrad’s Broadband Wireless Access division. “Each one can develop it for themselves.”

The Israeli company, which has an office in Delmar, New York, is now working with airports around the world to customize system configurations.

Telrad has also created Star Suite, a software network management program that can support any application an airport might require.

A 20-Year Job

AeroMACS is cheaper to operate and maintain than existing voice-based infrastructure, but it will take time to transition all airports to the new technology. Each aviation authority may choose to implement it in smaller stages. So far, some U.S. airports are using the system to collect information from surveillance sensors, which will help improve aircraft tracking on runways and taxiways, explained Rafael Apaza, principal investigator for NASA’s development of AeroMACS and senior communications research engineer at Glenn.

And for the first time, in 2016, NASA successfully transmitted aviation data, including route options and weather information, to a taxiing airplane over a wireless communication system. The sophisticated electronics used in airplanes are highly sensitive, so inexact wireless communication could disrupt those systems. Successfully eliminating the risk of signal interference while maintaining throughput capacity was what made this accomplishment so significant. Only then was the system proven safe for airplanes.

NASA engineers also proved that mobile assets such as emergency vehicles and laptop computers could be included in the wireless network. This will make it possible to track these assets when they’re needed.

To date, more than 50 airports in about 15 different countries are using AeroMACS to replace voice with data transmission. It’s estimated that it will take 20 years to transition over 40,000 airports worldwide.

When it’s fully implemented, it will be able to swiftly and securely route any ground communications.

A three-month pilot program at the Beijing Airport deployed the system for mobile assets and found that using AeroMACS instead of voice commands shaved 20 minutes off the time planes were spending on the ground.

As aviation authorities such as the FAA publish AeroMACS guidelines, Telrad and other hardware providers will be able to develop new tools to support the use of wireless communication at airports. Innovation will take off, according to Amsterdamer.

“This is going to be millions of dollars in innovation. When this is adopted by the airline companies, then the business can grow.”

Margo Pierce

Science Writer

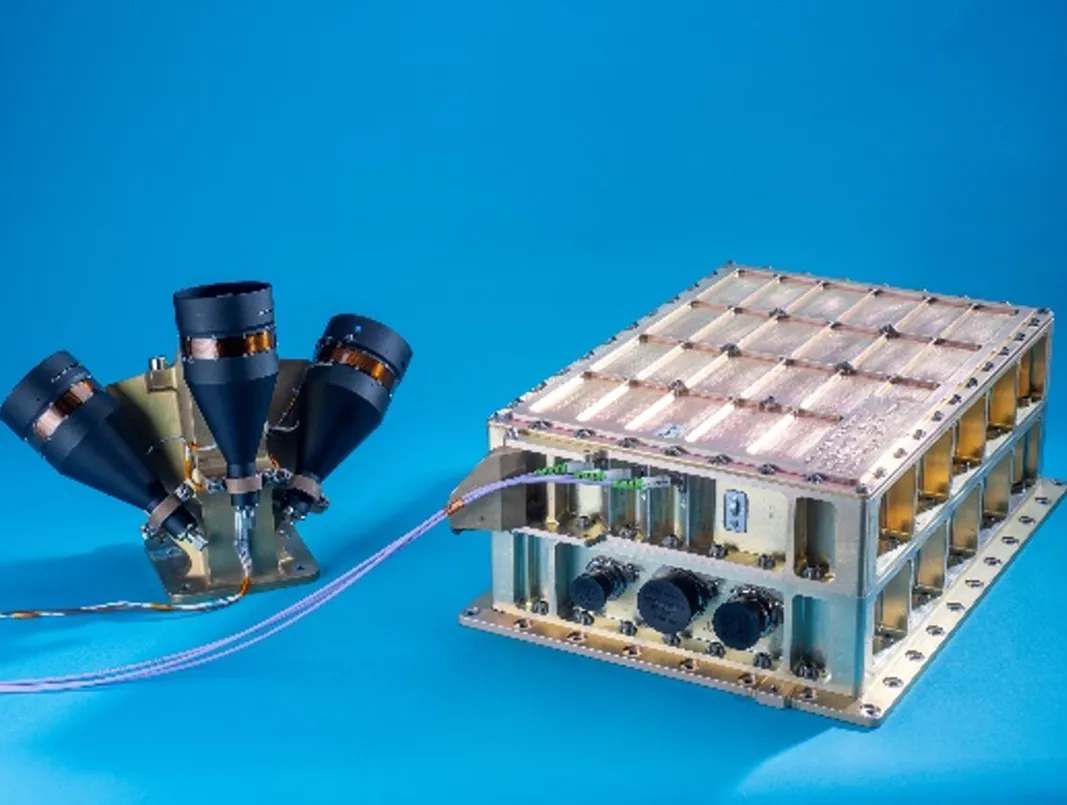

Air traffic control managers have communicated with airline pilots verbally for decades, but that’s about to change. The Aeronautical Mobile Aircraft Communication System (AeroMACS) allows aviation authorities around the world to send safety-critical information digitally and securely to airplanes once they’re on the ground. Telrad Networks is a technology provider that worked with NASA on the early testing of the system. Credit: NASA

The Telrad BreezeCOMPACT 1000 4G broadband base station, a modem and radio all in one, was named Product of the Year by the Wireless Internet Service Providers Association.

When the Federal Aviation Administration needed to develop and test a secure wireless communication system for use on the ground at airports, NASA was the logical choice. The sophisticated electronics used in airplanes are highly sensitive, so tests were necessary to prove such a system was safe. The Aeronautical Mobile Aircraft Communication System (AeroMACS) sends safety-critical information digitally and securely to airplanes, like this one used for the ground tests. Credit: NASA