Home-Grown Housing

Subheadline

Cultivating mushrooms to build housing on Earth, the Moon, and Mars

Smurfs have been doing it since the 1950s, but a group working with NASA is making it possible for people to finally enjoy the benefits of living in mushroom houses. Collaborating with an architecture studio, NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California, developed a way to use space-grown filamentous fungi to create a new kind of astronaut habitat — one that can also confer advantages on Earth.

Mushroom stems and caps can add flavor and nutrients to food, but fungal mycelia — the root-like parts that grow underground — can form part of an excellent building material. NASA and the architecture studio, known as redhouse, along with a few universities, researched the concept with funding from the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program. That research became the basis for Mycohab Foundation, a nonprofit focused on using mushrooms to create both sustainable building materials and economic opportunities.

To continue funding this effort, the foundation’s commercial arm, Mycohab Ltd. of Windhoek, Namibia, sells gourmet mushrooms to local retailers, markets, and hotels. Revenue pays for Mycohab’s other product — one-cubic-foot construction bricks. All this mushroom agriculture also serves another purpose: eliminating and reusing a destructive, overgrown, and water-hungry plant.

Acacia mellifera has been allowed to spread virtually unchecked in the African bush since the introduction of cattle farming. But when the environmentally harmful plants are ground into mulch, they become the perfect substrate, or soil replacement, for growing mushrooms. After the mushrooms are harvested for consumption, the mycelia-bound mulch they leave behind can be dried and baked into bricks.

Chris Maurer, principal architect with redhouse studio and cofounder of Mycohab, said the growing process the company is using has to be proven successful on Earth before growing the first habitats on the Moon from fungus.

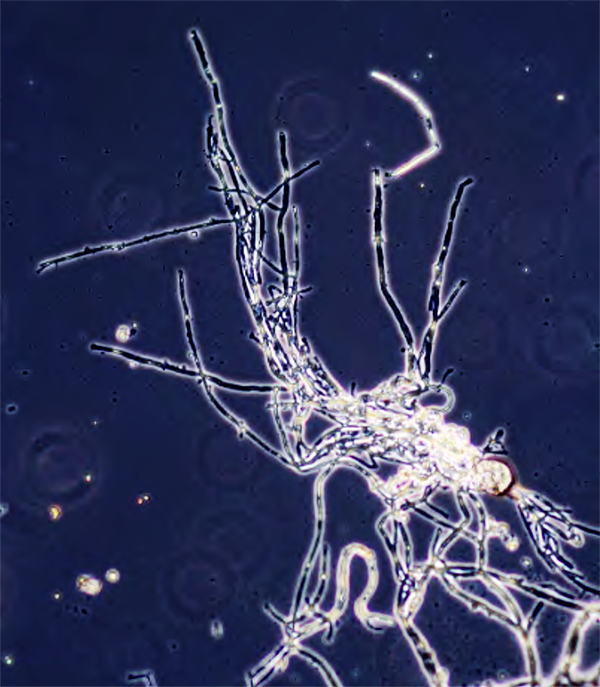

Mycotecture

Not just any mushroom or substrate will do to grow habitats. For the strongest building material produced in the shortest amount of time, NASA scientists chose the Ganoderma lucidum strain of mushrooms. The team then experimented with different kinds of substrates including one with lunar soil simulant to use with a custom nutrient hydrogel to produce nutritious mushrooms that won’t become toxic as they mature. But the substrate couldn’t have too many nutrients either, as it would encourage dangerous bacterial overgrowth. Finally, the fungal mycelia bound the substrate together while extracting nutrients in the growth process, forming the building material.

The experiments proved the viability of the dual use of fungus as food and construction material. But the real-life application of the theory is an economic success. Mycohab is using local waste as a substrate backed by NASA know-how to grow nutritionally balanced mushrooms in Africa. Mycofood requires less land, water, energy, and time to produce food with a level of protein comparable to meat. And the waste from cultivation provides a cheap construction material in communities with little to no extra resources.

“Mycotecture” — mycelia-based architecture — could flourish just as well using material available in off-planet locations, providing food and shelter anytime, anywhere.

And because the fungi can grow anywhere, it won’t be necessary to choose a landing site that suits the habitat — it’ll conform to the site, explained Lynn Rothschild, senior research scientist at Ames and principal investigator for the NIAC-funded project.

“If we’re going to do something long-term like plans are for human settlements on the Moon, we’re going to have to recycle materials,” she said. “What we’re trying to do by developing technologies to use off-planet is the ultimate sustainability experiment. Here, we go to the hardware store to get things we need, but there is no hardware store on the Moon. We have to think this through.”

For structures on another planetary body, NASA will use a lightweight scaffold and a nutrient hydrogel to serve as a substrate to grow the mycelia. All of this is enclosed in plastic-bag-like sheets that serve as the mold that controls the shape of the building. Think of a self-inflating raft: air flows in until it’s full. As the mycelia grow and consume the nutrients, they reproduce, expanding to fill the available space. If the sheets are dome-shaped, a rigid dome structure is the end result.

All of this could be done even before astronauts arrive. After humans land, more structures could be grown on nutrients from organic waste streams rather than feedstock launched from Earth. Incorporating dust and rocks from the lunar surface could save even more weight.

Moon-Shrooms

After proving the growing process worked, Maurer from redhouse created all kinds of objects — chopsticks, plates, furniture, and now a house. Ultimately, he wanted to find a way to use bio-fabrication in architecture where building materials are scarce or cost-prohibitive. Working with NASA gave him the opportunity to do just that.

“We sequester one pound of carbon dioxide for every pound of material we make, compared to concrete that emits a pound of carbon dioxide for every pound created,” he said. As long as it’s protected from moisture, this material will remain structurally sound and last as long as the conventional wood framing found in cathedrals and homes a hundred years old.

Using locally available biowaste requires a unique recipe to produce the desired building material. If a dense brick is needed, it’s necessary to choose the right type of mycelia and processing techniques such as compression and air drying or even baking.

Because Mycohab is using the waste created by the Acacia mellifera bushes, it can produce bricks cheaply and rapidly — in days and, in some cases, hours — thanks to the abundant supply. Using the bricks as the primary building material makes it possible to produce a small house for about $8,000, enabling the rapid construction of humanitarian housing or emergency shelter during a natural disaster or a refugee crisis.

These houses have the added benefit of generating almost no waste.

“Instead of putting demolished houses into landfills like we do now and generating a lot of harmful gases and toxins as they decompose, this building material can be mixed into soil, converting that carbon into new crops,” said Maurer.

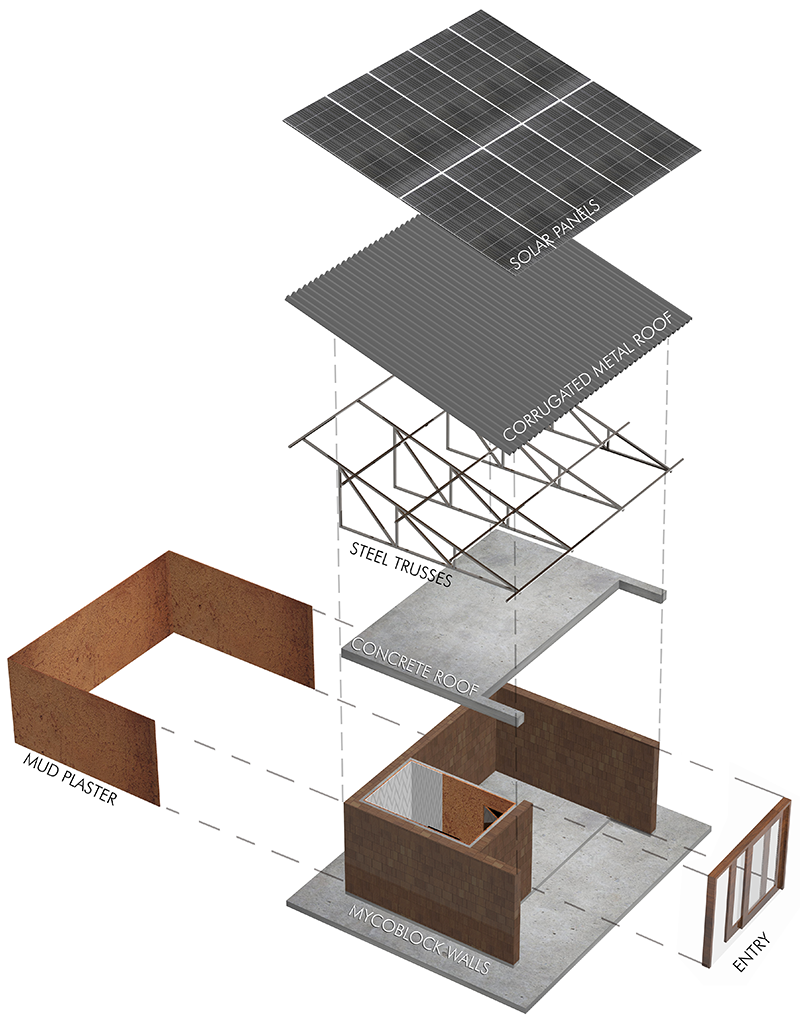

Mycohab completed a demonstration house in 2024 that uses mycelia as the structure of the building to provide an example of how the company’s bricks can be used to build an inexpensive, comfortable home.

A Bit of Home

While additional research is still needed, there are many benefits for terrestrial and planetary habitats. Mycelial materials are proven fire-resistant thermal insulators that don’t off-gas like plastic and glue. The density and material properties can be fine-tuned during production and have the potential to absorb indoor air pollutants, improving the interior environment. NASA is looking into these factors and more.

Melanin-rich fungi can also absorb radioactivity, even at levels found in space, so enhancing this characteristic could provide astronauts with additional protection. Adding lead from the Martian soil to the feedstock could provide even more shielding.

Materials made with mycelia also absorb sound and vibrations, ideal for long-duration spacecraft in low-Earth orbit. Rothschild is working with project partners to send an experiment to the future public-private space station, Starlab.

“Mycomaterials, even as a veneer, have psychological benefits. If you have the mycelia binding dehydrated woodchips, that veneer reminds you of home rather than trying to live in a stainless steel structure, which isn’t very human-friendly,” said Rothschild. “It’s also got acoustical benefits. There is a lot of vibration and noise on the space station. So if panels can do some noise absorption, that would be fantastic.”

In the meantime, Mycohab is growing and selling mushrooms while developing additional retail products such as teas and dietary supplements that can be exported around the world. Eventually, licensing for the proprietary mycelia growing process will be available to commercial builders wishing to take advantage of cheap biowaste near construction sites. Anything, from the straw that results from wheat or rice harvesting to acacia bushes, could be used in new homes or businesses.

“It’s a long detour to outer space to actually land this project in Africa,” said Maurer. “But it would have never happened if we hadn’t had this project with Lynn Rothschild, with NIAC. Had it not been funded by NASA, we wouldn’t be where we are today.”

Mycohab is growing gourmet mushrooms in areas of Africa where farming is difficult, using a technique developed for lunar farming. Credit: Mycohab Ltd.

Sales of gourmet mushrooms, available in Africa, fund Mycohab’s low-cost housing initiative. Credit: Mycohab Ltd.

This microscopic image shows fungal mycelia, the root-like threads that grow in a substrate and feed nutrients to the part we see — mushrooms. Credit: NASA

This stool created by a NASA-funded project proves it’s possible to fabricate furnishings using the same fungal mycelia that create bricks on Earth. Credit: NASA

The Mycohab staff uses a NASA-developed growing technique to create sustainable food and housing while removing a plant that chokes Namibia’s water supply and damages wildlife habitats. Credit: Mycohab Ltd.

Ivan Severus, site manager for Mycohab, holds a brick made from substrate used to grow mushrooms. This mycomaterial comes from woody mulch bound together by the fungal mycelia. Credit: Mycohab Ltd.

The first house constructed with mycomaterials demonstrates that it could be possible to build structures from in situ materials on the Moon and Mars. The illustration at left shows the building’s construction plan, while the top photo shows construction in progress. The photo above shows the final product, with mud plaster covering “mycoblock” walls capped with a concrete roof. On top sits a metal roof supporting solar panels. Credit: Mycohab Ltd.