Ferrofluid Technology Becomes a Magnet for Pioneering Artists

NASA Technology

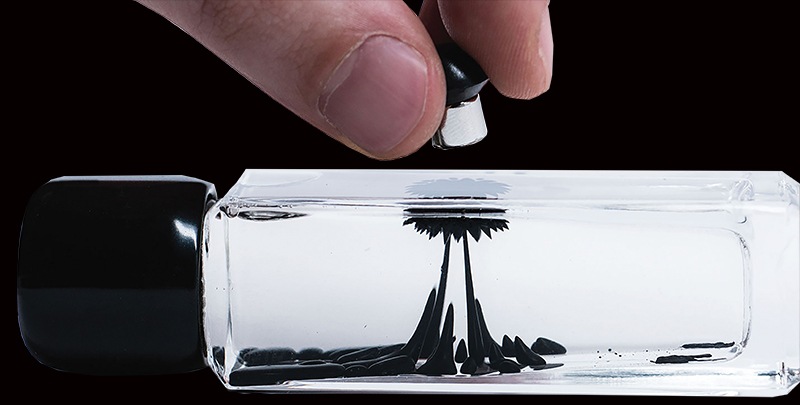

In 2008, when Nikola Ilic came across an online video of moving ferrofluid sculptures by Japanese artist Sachiko Kodama, with black liquid rising into swirling bristles that joined into quivering spikes, the artist-entrepreneur immediately wanted a ferrofluid display for his desk. “It looked like the T-1000 from Terminator 2 come to life,” he recalls.

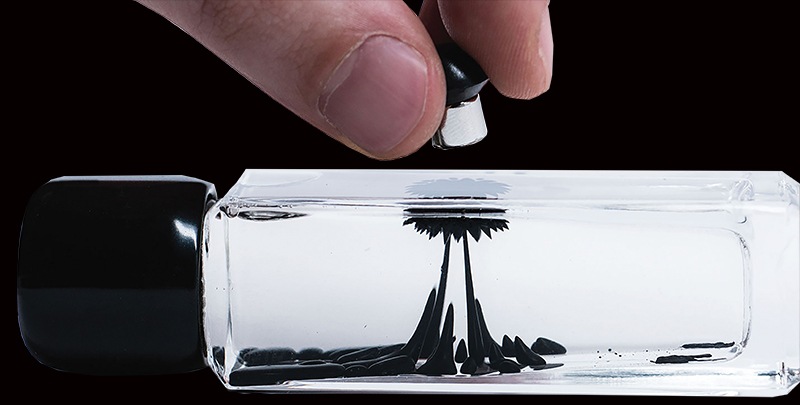

But he couldn’t find a display of the magnetized liquid available for sale anywhere online. So he decided to make his own—and soon learned why more people weren’t doing it: “It stains everything,” he says. In a typical display, a small amount of dark ferrofluid is placed in a clear glass chamber full of a clear suspension liquid. It’s then manipulated by a magnet outside the chamber. But if the ferrofluid mixes with the suspension liquid, the dark fluid quickly stains the glass and makes a mess.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that ferrofluid is not an ideal art material: after all, it wasn’t invented for aesthetic purposes, but rather for space travel. In the early 1960s, Steve Papell, an engineer at Lewis Research Center, now Glenn Research Center, came up with the idea of magnetizing rocket fuel as a way to draw it from a storage tank into an engine in the absence of gravity. He discovered a way to stably disperse magnetic nanoparticles throughout a carrier fluid, making the first ferrofluid. A few years later, a company called Avco Space Systems won a NASA contract to further characterize and develop ferrofluid and managed to create a variety of liquids that ranged up to 10 times the magnetic strength of the initial Lewis invention.

The basic trick to creating a ferrofluid is to make the magnetic nanoparticles so tiny they naturally spread throughout the carrier fluid, rather than settling out of it, and to coat them with a surfactant that prevents them from clumping together.

Technology Transfer

Two Avco engineers licensed the technology from NASA to found Ferrofluidics Corporation, now Ferrotec. The material has come to be used in a variety of applications, from loudspeakers to petroleum refining and chemical processing facilities, to semiconductor chip manufacturing (Spinoff 1980, 1981, 1993, 2015).

Since around 2000, a small but growing number of artists around the world, including Ilic, have begun using ferrofluids to create striking visual displays. They have faced some technical hurdles, though, such as the problem of staining.

On that front, Ilic took what he calls “the Edison approach: try 10,000 things, and one of them works, and you build on it.” He finally came up with a suspension solution that wouldn’t mix with the educational-grade ferrofluid he buys from Ferrotec. He guards his recipe closely but hasn’t patented it because he’s wary of patenting and the effects it may have on ingenuity, he says. “If someone else figures it out, they can go for it.”

In 2011, he started the online, Hamburg, New Jersey-based business Concept Zero. The site sells glass displays of various shapes and sizes, each filled with his clear suspension fluid and a small amount of black ferrofluid. When a magnet is placed close to a display, the dark fluid leaps into a hemisphere of spikes that follows the magnet around the glass.

Benefits

“People absolutely love it,” Ilic says of the Concept Zero product line. “A lot of people use it as a fidget—it’s sort of like a high-tech stress ball people play with while they think about other things.”

He says sales are healthy. “I can barely handle what comes in on my end, but I do it.”

Ilic has also developed glass chambers for a number of other ferrofluid artists. “People doing this in the United States, most of them came here as a starting point,” he says.

For example, he provided the chambers for artist Matt Robinson’s automated, lava lamp-like Ferroflow displays. He also provides suspension fluid to artist Linden Gledhill, who uses ferrofluid to create intricate abstract images. He helped promote (and Gledhill helped photograph) Mike Pecci’s horror film 12 Kilometers, in which the black, animated fluid plays the villain—a malignant entity released by Russian miners.

He also provided flat-panel chambers to designer Zelf Koelman, who used them with ferrofluid and an array of electromagnets to create a digital clock. Ilic has been working on his own flat panel display, with the electromagnet arrangement to be programmed by the user. He notes that designer Martin Frey used a similar setup to recreate an early video game with ferrofluid pixels. Ilic says he’s also experimenting with dried ferrofluid to create fixed sculptures.

Overall, though, the number of artists working with ferrofluid remains smaller than Ilic would like, he says. “The more talented people that get involved, the higher the quality of art.” On his website, he promotes designers new to the medium, as well as some of the original vanguard. “If anyone comes up with something I think is interesting, I put it on my website,” he says. “If it’s cool, it’s going up there, even if it’s a competitor.”

But Ilic says the scarcity of people repurposing this space-age substance for art is also part of its allure. “It draws people who want to pioneer something because the field isn’t saturated,” he says. “It’s like finding a new continent. You don’t know what’s around the corner.”

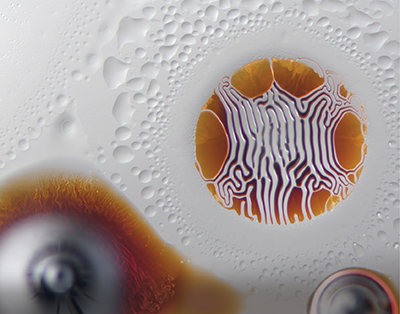

Concept Zero recently partnered with artist Linden Gledhill to launch a line of Gledhill’s art. He created the images by using a magnetic field to manipulate ferrofluids diluted with solvents and photographing the results.

Magnetic ferrofluids invented at Glenn Research Center have lately found their way into the art world. Nikola Ilic developed a suspension liquid that keeps ferrofluid from staining its container and founded Concept Zero, which sells products like Motion, pictured here.