Radar Device Detects Heartbeats Trapped under Wreckage

NASA Technology

Late on a sweltering morning in July 2016, David Lewis Jr. crawls into a concrete tube in a heap of rubble amid what used to be a Northern Virginia prison complex.

Only the toe of Lewis’ shoe is visible. As bystanders look on, R4 Inc.’s new FINDER device—that’s Finding Individuals for Disaster and Emergency Response—is trained on the scene and begins quietly clicking away, calibrating its radar to the objects and environment, before entering detection mode.

Within about three minutes of the radar’s initiation, it reports the results of its search on a handheld graphical user interface: “FINDER detected one victim,” the screen reads, above a high-definition photo of the concrete jumble where it spotted Lewis. It has also taken an infrared image to capture any possible body heat signature, and Lewis’ breathing and heart rates are reported.

Shawn Crockett, vice president of business development at R4, where Lewis is a project manager, notes that his colleague’s heart rate was higher than in another trial moments before.

“It was a little hot in there—there’s no breeze,” Lewis explains.

Using FINDER is still not an exact science: during the first test, the device mistook Lewis for two people. But even as it continues to improve, its lifesaving potential is already clear and has even been proven in the field, where it has been used to find earthquake victims trapped under rubble.

In the case of the double hit on Lewis, Crockett says, “For us it doesn’t matter. If we think there’s a life in there, we’re going in.”

The Edgewood, Maryland-based company is developing a line of such remote sensing devices to aid search and rescue teams, based on advanced radar technologies developed by NASA and refined for this purpose at the Agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

NASA has long analyzed weak radio signals to identify slight physical movements, such as seismic activity seen from low-Earth orbit or minor alterations in a satellite’s path around another planet that might indicate gravity fluctuations, explains Jim Lux, JPL’s task manager for the FINDER project. However, to pick out such faint patterns in the data, these devices must cancel out huge amounts of noise. “The core technology here is measuring a small signal in the context of another larger signal that’s confusing you,” Lux says.

In the early 2000s, the Department of Defense approached JPL wondering about the possibility of using remote sensing to determine whether there were troops alive on a battlefield and to take remote biomedical readings. Some work was done, and Lux says the latter application could still be of interest for monitoring astronauts in the International Space Station, for example. But funding dried up.

The work, however, was not forgotten, and years later, members of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate approached JPL, recalling that engineers there had worked on remotely detecting a heartbeat. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which falls under DHS, wanted such a device for locating trapped survivors. With DHS funding, Lux’s team set about developing the FINDER prototype.

Being NASA engineers, they were well-versed in the art of designing and packaging small, low-energy, rugged hardware, which the units required. Identifying working hearts and lungs by reflected microwave radar was trickier, but they had picked out slight movements from overwhelming data streams before. “This is a combination of a bunch of things NASA has been doing,” Lux says. “A lot of the pieces of this existed in some form or another.”

Once the engineers were able to identify a heartbeat, they had to further refine signal-processing algorithms to distinguish a human heartbeat. For example, even a large dog has a faster heart rate and, especially, a faster breathing rate than a human, Lux explains. And to pick out multiple victims, the device had to be able to recognize the rhythms of distinct pairs of heart and breathing rates. This is possible because the heart speeds and slows with each breath, says Lux.

FINDER can detect up to five separate victims in a given area.

Technology Transfer

R4’s founders, two U.S. Army veterans, came across an online article about FINDER several years ago, after JPL had developed a prototype and DHS had tested it. The California Institute of Technology (Caltech), which manages JPL, was looking for a company to commercialize the technology.

R4 reached out, and before long, Caltech had awarded licenses for FINDER to R4, as well as the company SpecOps Group Inc., which is working to commercialize its own version of the technology.

Over the next couple of years, R4 developed lighter-weight housings for the technology, made it more rugged, and improved the graphical user interface. “We improved all those things so it’s something a first responder could use in a real-world situation,” says Lewis.

A big test and major success came when a 7.8-magnitude earthquake rocked Nepal just northwest of its capital of Kathmandu in late April 2015, killing more than 8,500 people. Lewis’ father, one of R4’s founders, arrived four days after the quake with two FINDER prototypes and joined search and rescue crews. Using the devices, rescue workers in the hard-hit village of Chautara located two men trapped beneath the remains of a textile factory and two more pinned under the debris of another building.

Upon their discovery, all four men, who had been buried in rubble as deep as 10 feet, were rescued. They all survived.

Despite this triumph, the experience also exposed weaknesses the company would go on to address. The JPL version of the device had sensors facing in four directions, making it difficult to estimate a victim’s location, so current models look in just one direction at a time. The company also decided that a five-minute lag time for calibration and detection was too long and managed to cut that time in half.

And rescuers in Nepal found that some devastated areas were too difficult to navigate for the device to be put to use. R4 has since begun mounting units on drones and land vehicles.

Benefits

FINDER has proven capable of detecting humans through 30 feet of dense rubble and up to 100 feet away in the open with 80 percent accuracy. That’s up from the JPL prototype’s 65 percent accuracy.

In its current iteration, it is most useful in confirming suspicions that a live victim may be trapped in a given area, whether the hunch comes from human witnesses or search dogs, says Crockett. But he says the company is working on what he calls “persistent detection”—continuous scanning and detection while the FINDER is in motion, searching for survivors as it passes one heap of rubble after another.

In October 2015, FEMA officially announced it would provide funding to U.S. municipalities that apply to purchase R4’s FINDER units, which are now on the agency’s Authorized Equipment List under the category of “seismic, acoustic, and radar devices and accessories for locating trapped and entombed victims not detectable by other means.”

“This allows first responders to have some type of funding to get these new technologies,” says Lewis, noting that emergency response teams in Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco, as well as Virginia Task Force 1 and several nonprofit organizations, have expressed interest.

Meanwhile, FINDER’s first official customers are the Army’s Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate and the Quito Fire Department in Ecuador. As the company demonstrates the technology around the country and the world, it has also drawn interest from Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Guatemala, Columbia, and Argentina, Crockett says.

While most of these are in quake-prone regions, R4 is working on a security pilot program in the UAE’s capital of Abu Dhabi. Due to the heat, drivers there are allowed dark tint on all windows, so border police are experimenting with using FINDER to determine whether the number of passengers in a vehicle matches the number of passports presented. By charting heart and breathing rates, the devices may also be useful in spotting telltale panic.

“People are coming up with all kinds of ideas for ways we could use it,” Crockett says.

The company has also designed prototype versions that would mount on a remote-controlled octocopter, a pickup truck, and a motorcycle, all to search hard-to-reach areas. Efforts are underway to combine GPS and lidar for accurate, continuous navigation aboard the drone, as well as to combine readings from a hovering drone unit with those from another FINDER on the ground to more precisely triangulate a victim’s position.

Even in its current state, though, FINDER presents a capability never seen before, and one that rescue crews welcome gladly wherever the company brings it, Crockett says. “It’s a one-of-a-kind technology that really does save lives.”

With all the enhancements R4 is making to render FINDER more and more effective across a variety of situations, Crocket says, “The secret sauce is in the algorithms and the specialized sensors that we use.”

That’s the hardware and software rooted at JPL, which continues to act as a strategic partner, for example working with R4 to try to enable distance readings and helping the company get FINDER into testing events and demonstrations, Crockett says.

“They’re still supporting the product, so that’s been a great help to us,” says Lewis.

After a magnitude 7.8 earthquake hit Ecuador in April of 2016, R4 President David Lewis Sr. brought the company’s FINDER system to look for victims trapped under rubble. Here, Lewis, right, shows local firefighters how to operate the system.

R4 had to do quite a bit of its own development to make FINDER functional, although JPL engineers have continued to partner with them. Though the units are now available for sale, the team continues to improve the technology.

R4 is developing a model that can continually scan for trapped victims while passing over mounds of debris on an octocopter drone. Other models are meant to fit on a truck or a motorcycle.

Earthquakes are the deadliest of natural disasters, crushing tens or even hundreds of thousands of people under fallen buildings. Inevitably, many survivors are trapped alive but are difficult to find under the rubble. Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) used their experience with analyzing weak signals to develop a technology that uses radar to identify unseen people by detecting their breathing and heartbeat. A company called R4 Inc. licensed and developed the technology and is now making sales to government entities in the United States and abroad. Image courtesy of Voice of America

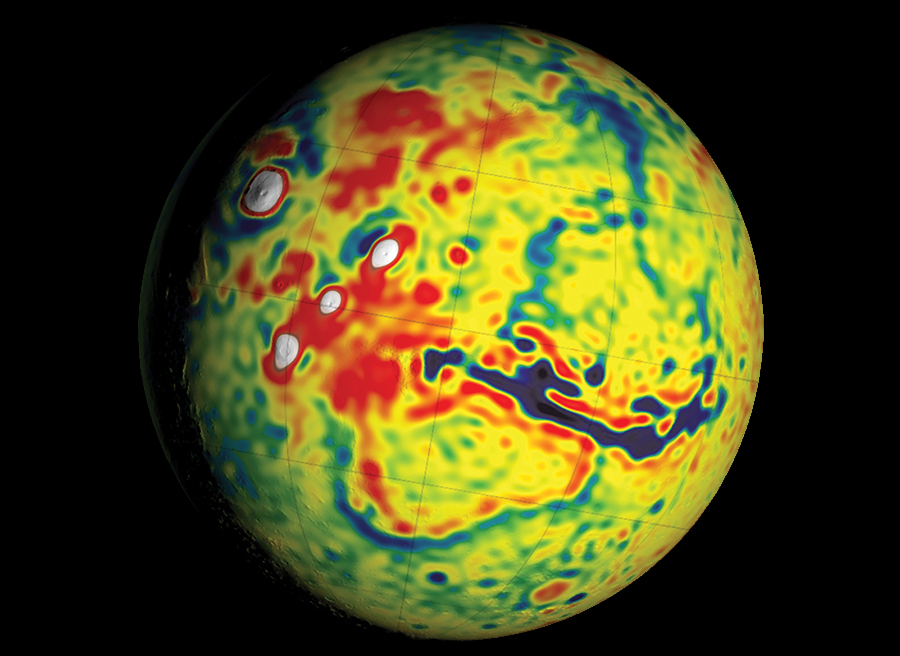

NASA has long experience analyzing weak signals to detect slight physical movements, cancelling out huge amounts of noise. Here, Doppler and range tracking data from three Mars orbiters were used to detect slight movements in their paths that indicate gravity fluctuations, allowing scientists to construct a gravity map of the entire Red Planet.