Biometric Sensors Optimize Workouts

NASA Technology

What if, as a pilot was pulling heavy G-forces and headed toward a blackout, a voice in his or her ear said, “Pull out of the turn”? What if ground control had a screen with an astronaut’s biometric indicators, and it set off a warning when he or she was hitting a danger zone?

It could be helpful, says astronaut Yvonne Cagle, not least because astronauts and fighter pilots tend not to say anything when they’re feeling funny: “We’re very driven to complete the mission, and we may not be as aware of physiologic urgencies until it actually interferes with our performance.”

But if they wait, say, until their vision is graying out and they’re about to lose consciousness, it may be too late. “Much of what we do is so intense, fast, and dynamic that, by the time you have symptoms, it’s very difficult to intervene,” Cagle says.

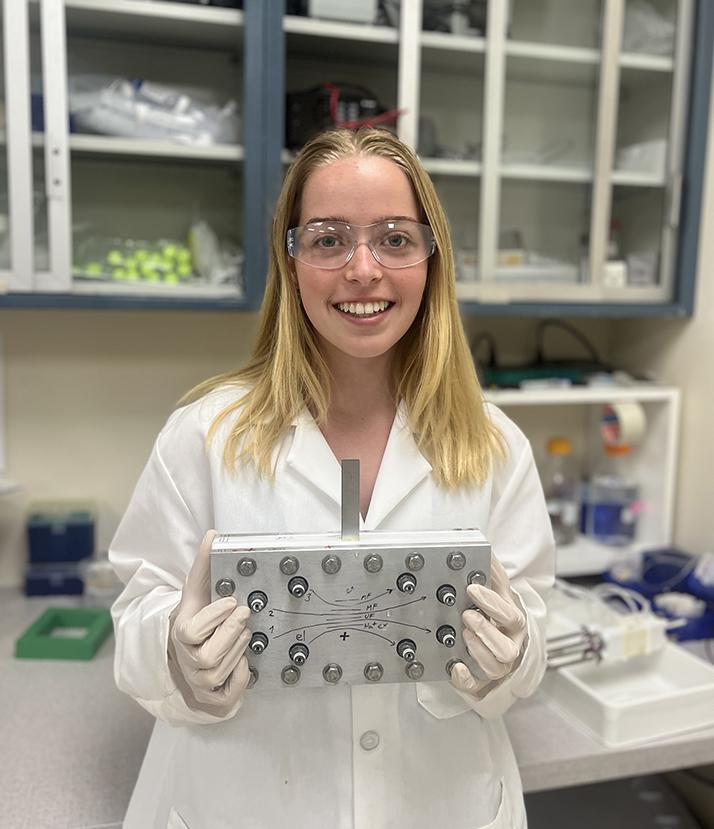

That was the motivation behind a research project Cagle mentored with Omri Yoffe, an Israeli entrepreneur whose team won the opportunity to work with Cagle and other NASA personnel in 2011 as part of a program run by Singularity University. The organization, which has a Space Act Agreement with NASA, aims to be “a global community using exponential technologies to tackle the world’s biggest challenges,” from water scarcity to universal education to space exploration and more.

For their project, Yoffe and his team aimed to improve biometric monitoring for pilots and astronauts, and Cagle says she helped give “some of the relevant clinical and operational situation awareness, to make it relevant to different scenarios that might come up and also streamline it for air or space operations.”

Technology Transfer

Yoffe and his team came up with a prototype during the three-month Singularity program, and he says the experience was immensely beneficial when they decided to create a new, commercial biometric sensor.

“It really set the bar, to be able to measure biometrics in a very noisy, very dynamic aerospace environment,” Yoffe says. That experience “trained the team and trained our know-how to be able to approach the consumer market in an easy way.”

For the consumer version, the new company, New York City-based LifeBEAM, had to go back to the drawing board, because, as Yoffe explains, “the expectations of the consumer user are not at the level of the astronaut, so you can make some compromises at the R&D level” to achieve a lower cost.

But that wasn’t difficult, he says, because the team had already worked on the harder task of meeting NASA-level specs. “We started at the highest bar, so then it was easier work to do it for the consumer level.”

Benefits

LifeBEAM is now offering a product named Vi: “the first voice-activated, fully immersive, and real-time AI [artificially intelligent] personal trainer.” Like the biometric sensor the team worked on at Singularity University, Vi tracks heart rate, but since it is designed for exercise rather than aerospace, it also tracks steps, mileage, weather, elevation, and more.

And unlike other wearable exercise trackers, this one is built into voice-activated earphones, so it can communicate with the user, responding to voice commands to read out heart rate, for example, and analyzing data to make suggestions on how to maximize fat burning or work toward any other set goal.

“We’ve created the first true AI fitness companion,” Yoffe says, noting that Vi can help with any fitness plan, whether it’s running a first 5K, eating healthier, or sleeping better. “We’ve leveraged our core bio-sensing tech into a more self-learning and interactive system.”

Vi seems to have hit a nerve: an initial funding round through Kickstarter raised nearly $1.7 million and sold more than 8,000 units.

Cagle says she’s pleased to see the work Yoffe and his team did for aerospace find a purpose here on Earth. “It’s exciting to show how innovations like LifeBEAM can be applied in a lot of different operational environments, and reinforce that there are benefits that come back from space that have universal applications.”

Based in part on expertise gained through a NASA-linked program, LifeBEAM built an artificially intelligent “personal trainer” that aims to use a biometric sensor to maximize the impact of exercise.

Pulling heavy G-forces can cause a pilot or astronaut to black out. A biometric sensor could monitor heart rate and other indicators to give a warning when he or she hits a danger zone.