Redefining the 'Rugged' Video Camera

Subheadline

A new rocket-riding camera is tough enough for Earth

Dramatic video of the first flight of an inflatable heat shield, from its deployment in low-Earth orbit through its screaming entry into Earth’s atmosphere and the following splashdown, gave NASA essential information about the performance of its new Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerator (HIAD). It also proved the capabilities of a new rugged video camera mounted under the heat shield. The camera, developed using patented NASA hardware and agency expertise, survived the vibrations of blastoff and atmospheric reentry, as well as the cold of space, and a commercial version is now ready for extreme conditions on Earth.

Whether it’s mounted to the underside of an airplane to live-stream takeoff and landing for the pilots or added to drilling infrastructure to stream a real-time view of equipment operation, the SPC-S2010 camera, the commercial version of the NASA flight-tested one, is likely the most rugged video camera available.

“It’s very rewarding and very advantageous to work with NASA,” said Greg Pangburn, CFO of Imperx Inc., the Boca Raton, Florida-based company that built the camera. “We learned a lot of new things that will allow us to offer something to our customer base that we’ve never had before.”

Too Cold to Handle

The camera was initially developed to ride on the Space Launch System (SLS) during the Artemis missions to capture crucial moments like the boosters’ separation from the core stage. Indeed, an earlier version flew on Artemis I just days after the HIAD flight in November of 2022.

As engineers at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, considered the requirements for a camera that would fly into space on the outside of a rocket, they decided to start with the Imperx Bobcat, a high-performance, industrial camera the agency had been mounting on rockets for years. Jarret Bone, a mechanical engineer working on the SLS camera system, said his team wanted to avoid designing a camera from scratch. Working with an existing camera helped simplify the process by shortening the time needed to perfect the system.

“There just aren’t a lot of cameras that can live in space that have the optical requirements for resolution and the image size we needed,” said Bone. But the Bobcat had to be enclosed in a rugged housing incorporating the necessary electrical and mechanical components before it could be flown in space. This was the camera that flew on Artemis I.

In the meantime, however, Imperx launched its rugged Cheetah camera model, which Bone’s team found to be the only commercial camera that performed well on the most difficult challenge for a camera in space – radiation. So the team set about building a housing for that model to fly on later Artemis missions.

With an eye toward supporting a commercial camera for future missions, NASA engineers approached Imperx to collaborate, and the company readily agreed. The agency subsequently patented the space housing and internal heating design technology for the Cheetah.

Temperatures around a rocket traveling through space get cold enough to damage electronics. Imperx was happy to collaborate on adding a heater that could be turned on and off as needed, but it soon became apparent to Pangburn that it would be easier and quicker for the company to engineer NASA’s requirements into a new camera model.

‘Built Like a Tank’

Imperx created several versions of a custom camera for the Marshall team to test. The data from every success and failure informed changes, resulting in new models and more testing.

“Environmental testing is expensive, too expensive for us as a small business,” said Pangburn. “Because of the extensive testing that NASA requires and their many areas of expertise, we learned a lot of things along the way.” Recommendations for non-off gassing materials to eliminate interference with camera performance and changes to conformal coating are just a few tips from NASA being incorporated into numerous Imperx cameras.

A question about screws served as a learning opportunity that, for Bone, illustrates how aerospace expertise can benefit an existing commercial product.

“Imperx builds really elegant cameras – they’re small, compact – but they use these tiny, millimeter-sized screws,” he said. The company pointed out the housing was “built like a tank,” believing that would be enough protection for the existing screws. But NASA’s extensive experience building technology to withstand the extreme conditions of launch and spaceflight resulted in another improvement. Bone’s team found a way to wire the screws together so they couldn’t come loose.

The NASA technologists invited the company to view environmental testing. The demonstration of how forceful vibration can effectively unscrew bolts gave the company a new definition for “extreme,” according to Pangburn. And it was useful for developing cameras for use in aviation, drilling, and mining.

The second design easily passed the vibration test.

Adding New Customers

Bone credits the company with the “highly effective” firmware needed to pull the data from the sensor, format it, and transmit it. “That’s expertise we didn’t have,” he said. Keeping the manufacturing cost low to provide an off-the-shelf part that’s cheaper than anything the agency could have produced also benefited the project.

Even before the Bobcat camera launched on SLS, Imperx was able to develop and offer a commercial version of the new, ruggedized Cheetah camera. The SPC-S2010 is a two-megapixel, high-definition camera that incorporates the patented housing, a heater along with a built-in ring light, and two-kilovolt power isolation. This isolation protects internal electronics from unstable power sources. Whether that’s a power surge or static transmitted by attached equipment, this feature can prevent damage that could be caused, for example, by a lightning strike nearby. Specialized valves allow air to escape in the vacuum of space but don’t let any air in. It was a beta version of this ruggedized Cheetah that recorded the HIAD deployment and descent, proving its space worthiness for future Artemis missions.

Pangburn said the NASA collaboration is directly tied to an added $10 million in sales, which is significant for the company. But even more important to Imperx is the opportunity to bring some camera business back to this country. Noting that commercial aviation uses a variety of cameras to improve takeoff and landing safety, Pangburn said European technology has been meeting that need for years.

“This experience has helped us make a camera that can withstand being mounted on an airplane, which goes from ground level up to 36,000-40,000 feet and then comes back down,” he said. “It works perfectly during all of those altitude changes, whether it’s hot or cold outside, if it’s raining or snowing. It’s helped our expansion into aviation systems.”

‘If It’s Good Enough for NASA’

Bone hopes NASA will be a future customer because “the environmental range on these cameras is insane,” he said.

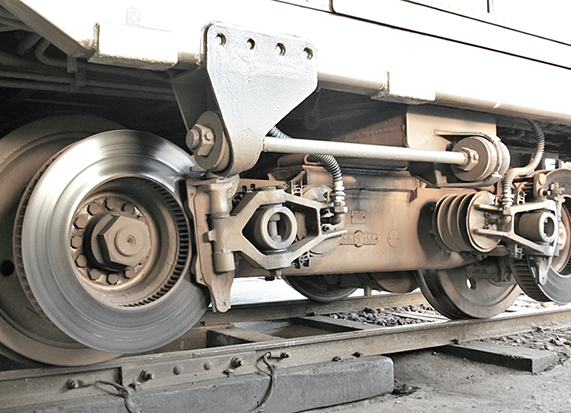

The video footage from the NASA flights is going to come in handy when talking to potential customers, whether their industry is commercial space, aeronautics, oil and gas, mining, or trains, said Pangburn. “I’m sure the response will be, ‘If it’s good enough for NASA, I’m sure it’s good enough for me.’ Because what customers want is a proven concept.”

Imperx credits the public-private partnership with giving its small business a big boost.

“NASA engineers are highly educated, motivated, and they’re imaginative. They are willing to try things that haven’t been tried before,” said Pangburn. “We’re in the camera business, but there are so many other businesses that can work with NASA and learn from their expertise.”

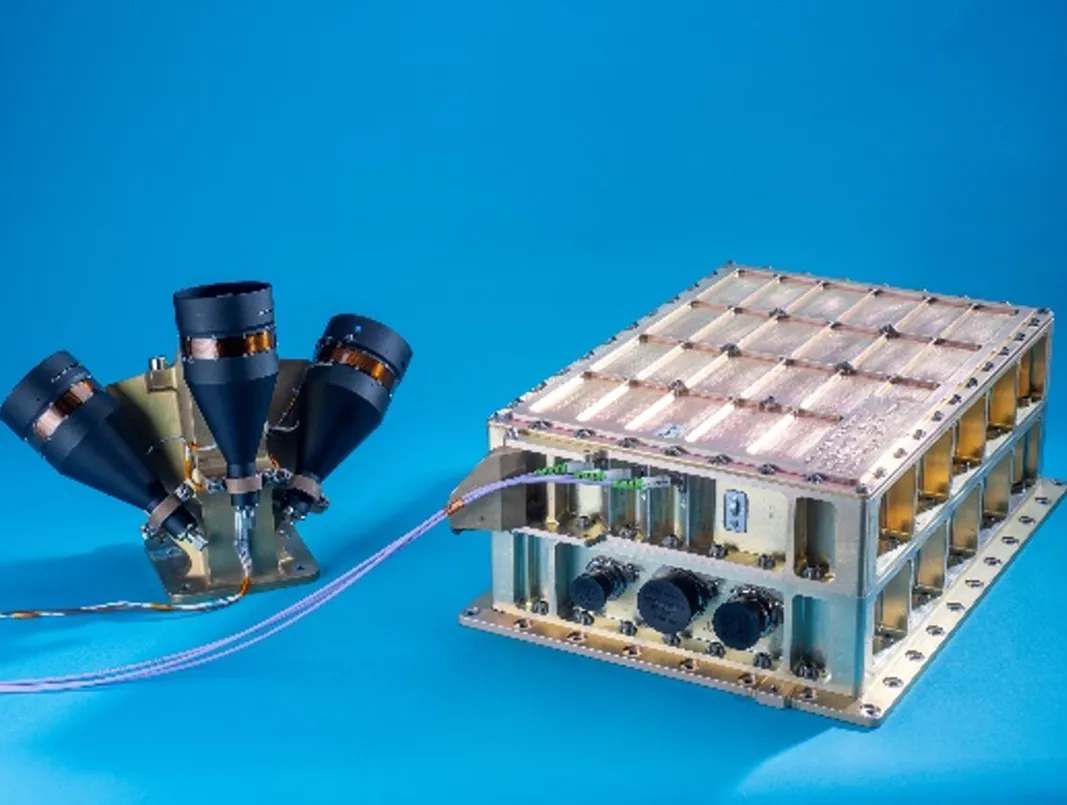

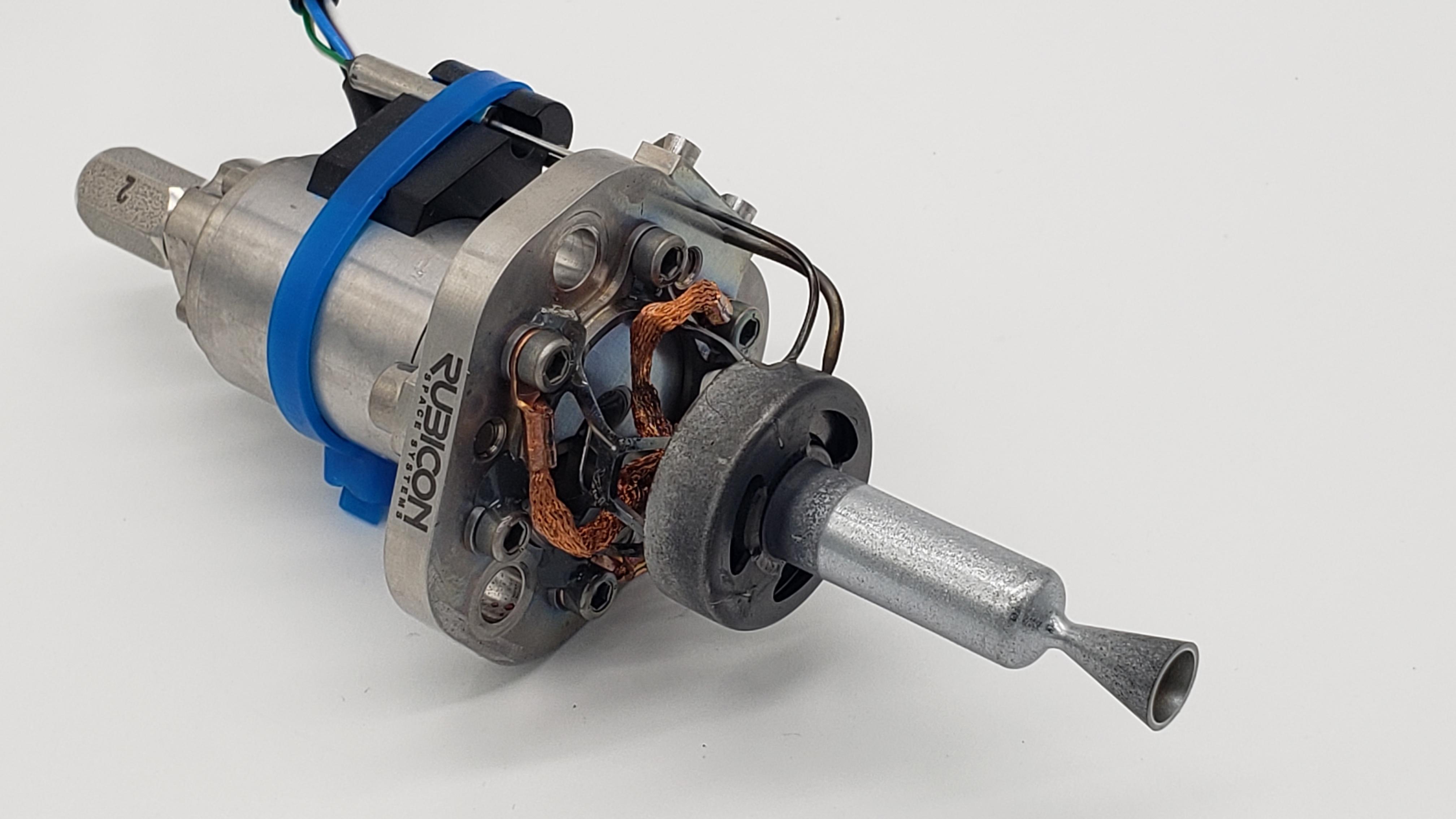

Specifically designed for launch vehicle applications, the Imperx S2010 camera employs NASA-developed ruggedized housing and internal electronics design. The camera has an internal heater and an integrated LED illumination ring that supports continuous lighting. Credit: Imperx Inc.

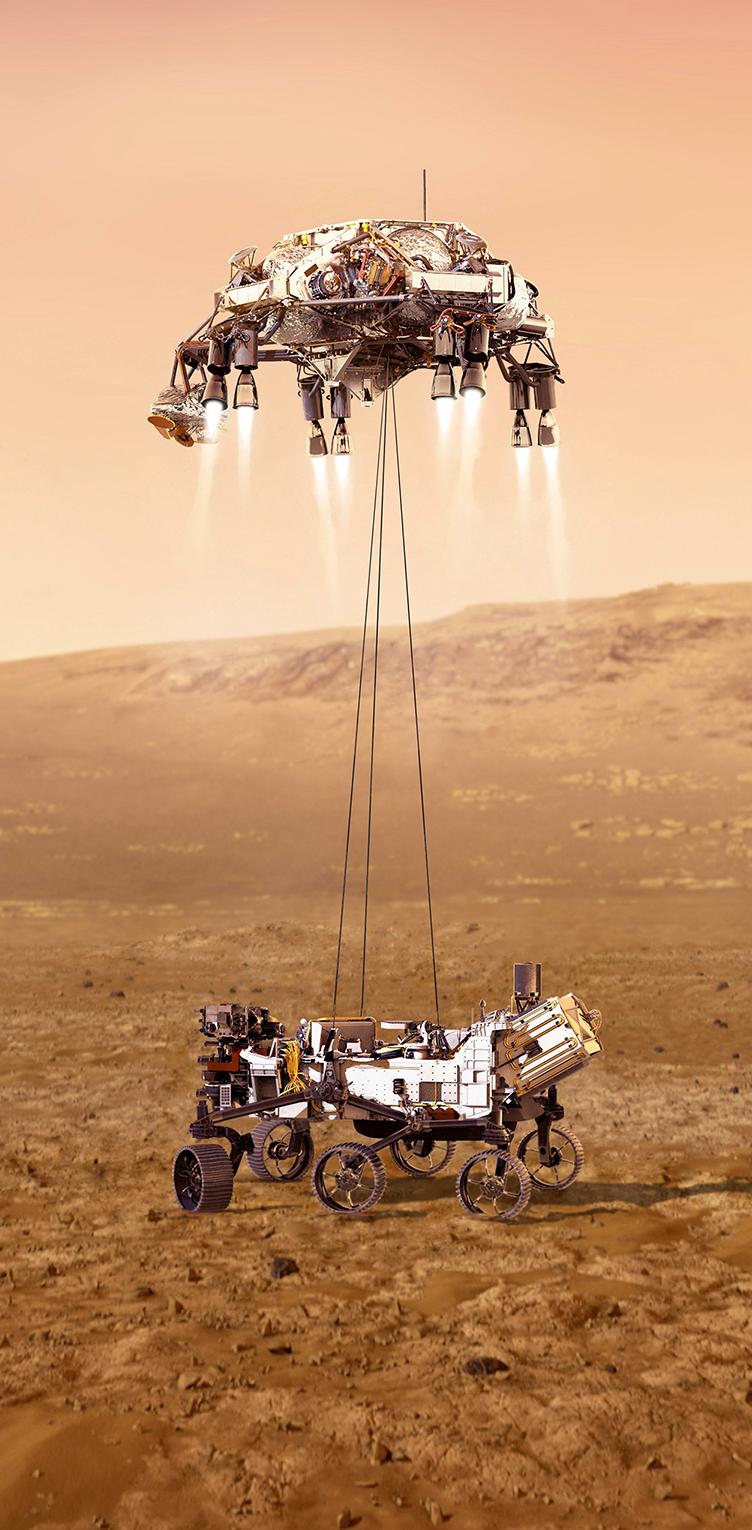

NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket carried the Orion spacecraft on the Artemis I flight test in 2022. Thanks to seven strategically placed Imperx ruggedized video cameras on the exterior of the rocket, technologists watched the launch from the countdown through rocket booster separation from the rocket’s vantage point. Credit: NASA

A ruggedized video camera designed to withstand the shock, vibration, and extreme temperatures of space could be durable enough to mount to train undercarriages for constant brake monitoring to ensure timely maintenance. Credit: Tennen-Gas, CC BY-SA 3.0

Seven Imperx ruggedized cameras mounted to the exterior of the SLS rocket were able to capture the Artemis I launch, including a live recording of booster separation and jettison. Credit: NASA