Flying in the Fast Lane with Air Traffic Software

Subheadline

NASA aviation research helps coordinate air traffic worldwide

Think of the national airspace as a complex highway system, but with planes. They’re all moving at different speeds and converging on relatively few airports, intent upon arriving safely and on time. Like the highway patrol, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) oversees the busy thoroughfares overhead. But unlike a patrol car with a flat tire, the systems used to manage all that air traffic cannot go down for repair or upgrades.

Making any change is akin to trying to replace a tire while the car is moving, said William Chan, project manager for the Air Traffic Management Exploration project at Ames Research Center. NASA has spent 30 years researching, developing, and evaluating software tools for FAA air traffic management decision-making.

Major airports operate at capacity year-round, with incoming and outbound flights in the air and on the ground moving around each other in a complicated, high-stakes freeway interchange. All the while, they’re directed by the various air traffic entities responsible for different stages of flight. Keeping different zones of air and ground activity safe and efficient requires multiple groups. Each uses a unique software program to support its responsibilities.

The FAA’s air traffic controllers in the U.S and their counterparts in other countries manage how aircraft access and fly in their skies. In the U.S., controllers in the airport control tower keep an eye on the aircraft flying nearby, grant permission for landings and take offs, and monitor movement on the airport surface. Higher up and further away, other controllers guide the aircraft safely to their destination.

This division of labor makes flight the safest mode of transportation available, even in tough conditions. There are approximately 5,000 commercial aircraft in the sky over the U.S., according to the FAA. Those are part of the 100,000 flights in the air at any given time around the world. “They all have to be managed and coordinated, so that they don't create bottlenecks in the airspace system,” said Chan.

“Everything works well in good weather. It's when there's bad weather, or problems happen at an airport, that the complexity becomes acute.”

From “a Clipboard and Intuition” to Cooperative Decision-Making

Poor weather conditions slow down the rate of landings and takeoffs in much the same way cars must move slower getting onto and off a freeway during inclement weather. Historically, the inability of disparate and legacy software programs to share data has presented an additional challenge to keeping airport capacity and demand in sync.

To facilitate and streamline communication across the various air traffic control entities, NASA has done extensive research into the best decision support tools for traffic managers. One recent outcome of that work is a software system called Airspace Technology Demonstration 2 (ATD-2). This software integrates arrivals, departures, and surface traffic management, using flight data to help air traffic managers improve efficiency and predictability of these operations.

“When I was in Alaska, it was a clipboard and intuition. There was some information, but it wasn't integrated digitally,” said Chan. ATD-2 brings flight coordination into the digital age.

The suite of technology, currently being tested at airports in North Carolina and Texas, makes it possible for air traffic managers to see the most current data related to each area of operations. This includes information sent by the airlines, such as flight cancellations, modified departure times, and route changes. When changes are needed, the FAA and flight operators can readily collaborate to meet the need. This automated approach to information sharing required years of analysis and testing.

Metron Aviation Inc., a subsidiary of Airbus, collaborated with NASA on the research needed to develop numerous tools for the FAA, including ATD-2. Over the course of 10 years and multiple NASA Small Business Innovation Research projects, most of them through Ames, the Herndon, Virginia-based company also developed companion tools to let businesses automate their communications, in support of the FAA's effort at collaborative communication. The company’s Harmony and Harmony Horizon software packages help any business using or managing airspace, whether to move goods or people, stay current with the ever-changing conditions of air travel.

Translating Weather Delays

Drawing on Metron’s experience with NASA research, the Harmony commercial software package does more than just share flight data. Proprietary algorithms track flights, predict weather impacts, and propose alternative flight paths. Harmony has other tools that keep users up to date with air traffic around the world.

Bob Hoffman, vice president of research and engineering for Metron, described the software’s weather translation tool as a “big leap” in air traffic management.

“It takes a weather forecast and then translates it into the actual impact it has on the air traffic system,” he explained. “We take the forecast map, and we layer that on top of the air traffic-demand forecast to figure out when and where the imbalances might be. Which airports will experience a bad impact? What's the reduction in capacity?”

With that information, Harmony can quickly calculate fuel savings for a new route, the cost of time spent waiting on the ground, and other factors related to rerouting and ground delays. Instead of guessing, airlines can make informed decisions about scheduling around bad weather and high traffic volume.

Businesses such as FedEx are using Harmony Suite for Airlines to track their cargo fleets and to improve fleet performance. Beyond the tarmac, modeling of emissions, aircraft noise, and fuel consumption provide data about alternatives for more efficient operations. The software can also perform environmental analysis providing input on how weather could impact airplane performance. It can be used to conduct an airport review and airspace analysis to inform decision-making.

Airlines gain cost savings and other benefits from these decision-making tools. For example, to avoid burning fuel, planes can be scheduled for a slightly longer wait at a gate until their departure spot is available. This in turn allows passengers to wait inside the airport.

International Cooperation

Harmony is now being adopted by air traffic agencies around the world. Colombia, Singapore, South Korea, Australia, and South Africa are all using the program to help manage their air traffic. “The global community is eagerly adopting these paradigms we developed in the U.S., but tailored to their particular needs,” said Chris Jordan, Metron’s president. “They have recognized the importance of having the right data and common situational awareness.”

Metron also offers a scaled-down version of the software for business use or neighboring air traffic agencies called Harmony Horizon. This web-based program provides current air traffic management information that helps the corporations relying on air deliveries stay current with the ever-changing conditions in airspace. This version doesn’t include the level of data required of airlines for airport scheduling decisions.

With the likely introduction of new kinds of aircraft — regional electric planes, supersonic commercial aircraft, local air taxies — the virtual highways overhead will grow more crowded. Thanks to interconnectivity afforded by this air traffic software, simple updates such as new algorithms will quickly update the capabilities, keeping the system operating without any downtime required.

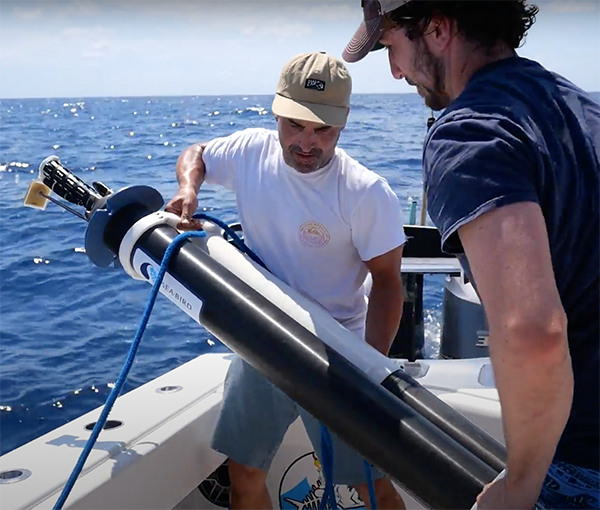

Pilots depend on air traffic controllers, ground control and other air traffic management professionals to provide up-to-date flight data. Metron's flight management software facilitates the sharing of essential data, such as helping a pilot know where to land, at airports in several foreign countries such as Australia and South Korea. Credit: NASA

Lights on the runways of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport help pilots land and taxi along the path designated by ground control staff, only one part of managing the movement of aircraft into and out of an airport. Metron Aviation Inc. software, developed with NASA support, helps businesses such as FedEx track their flights across all air traffic control entities. Credit: John Murphy, CC BY-SA 2.0

NASA’s Sherlock Air Traffic Management Data Warehouse shows one day of air traffic for Charlotte, North Carolina's international airport in the mid-2010s. There can be over 5,000 aircraft sharing U.S. airspace. Credit: NASA