Drone Company Makes It Rain Forests

Subheadline

Flying Forests cofounder builds on NASA science and technology experience

During a particularly rain-soaked week in Peru’s Amazon jungle, not far from the city of Puerto Maldonado near the Bolivian border, 20 soldiers from the Peruvian Army helped Lauren Fletcher prepare ammunition for an upcoming operation. It was early December 2024, and the same alliance had conducted a similar mission a year prior, just up the Madre de Dios River.

With 20,000 rounds on hand, they waited for a break in the rain. When it finally came, the whole thing was over in an hour and a half.

All 20,000 seed balls, packed with seeds of the smooth Crotalaria plant, were deployed across 25 acres of barren, sandy soil, shot from a single drone equipped with a rapid-fire launcher, to combat environmental destruction in this important ecosystem.

This was the first step in reforesting the land, which had been stripped during gold mining operations. The Crotalaria, a hearty legume, would establish ground cover to allow the introduction of other native species.

The soldiers were volunteers from a local military base, and Fletcher, thanks in part to his experience as a former NASA employee, had cofounded Beta Earth LLC, which does business as Flying Forests, the company that armed the drone and spearheaded the effort. Also on hand were several researchers from Wake Forest University’s Center for Amazonian Scientific Innovation, which helped fund the operation.

Flying Forests, which Fletcher founded with Irina Fedorenko-Aula in Reno, Nevada, in 2020, is not the first company to use seed-launching drones to regrow forests. That would be the pair’s first company, founded seven years prior.

Since Fletcher and Fedorenko-Aula created BioCarbon Engineering to harness what was then the very new power of drones for rapid, large-scale reforestation, several other companies have sprung up to do the same. But Flying Forests is the first to open up the technology for small-scale landholders.

From Animals in Space to Trees on Earth

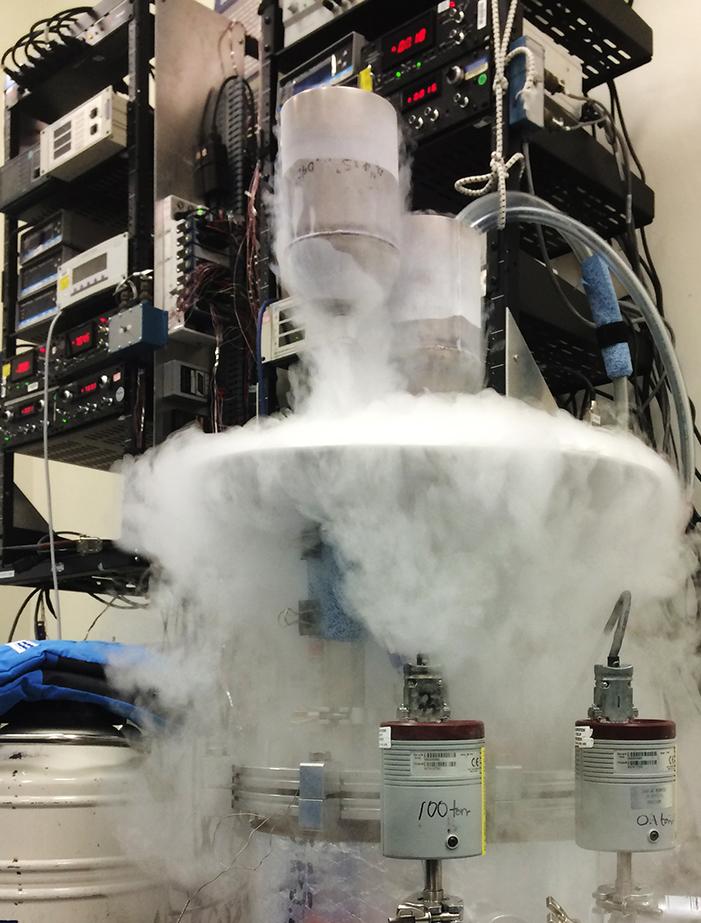

At both companies, Fletcher leaned on his prior experience at NASA, at the intersection of technology and biology. As part of his 20-year NASA career, he worked in life sciences programs at the space agency’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California. There, he qualified hardware for missions such as Neurolab, which studied the effects of weightlessness on the central nervous systems of animals of various species, and the Space Station Biological Research Program, which developed two major hardware suites for studying plants and animals in space.

“You have to understand the biology first, and then you design the engineering to match the biology you’re trying to support,” he said.

Later, while earning his Ph.D. under a paid NASA research program, he studied deforestation. When he tried looking into reforestation technology, he found that virtually none existed. “And I said, look, I work for NASA. We’ve got remote sensing, and we’ve got machine learning, and AI is coming along, and we’ve got robotic systems,” he recalled. “There’s got to be a way that we can combine these technologies to automate and accelerate reforestation.”

When drone technology hit the market in 2013, he and Fedorenko-Aula started BioCarbon Engineering, and he built the first seed-flinging drone. “It immediately captured the world’s attention,” he said. Other companies followed suit.

While that company, now called Dendra Systems, has been successful, it and others in the field developed technology and business models that work at large scales but aren’t cost-effective for smaller parcels of land. This locks about 80% of private forested landholders out of the conservation market, he said. “They’re going to be the ones that are going to solve the majority of our reforestation problem around the world.”

He designed a smaller, cheaper drone. Even more importantly, he said, Flying Forests operates on a franchise business model, equipping and employing local organizations that are already planting trees, with most of the funding that’s generated going back to local workers.

Ancient Tech Meets High Tech

The drones don’t launch individual seeds but rather seed balls, consisting of a clay-like base, plant food, and anti-predation materials such as garlic or cayenne pepper, with the seeds mixed in. Egyptians invented the concept thousands of years ago.

The technology to deploy the seed balls, on the other hand, builds on Fletcher’s experience at NASA. It starts with a biology question, he said: “How do you get things to grow that you’ve basically thrown out the side of a drone?” Depending on soil biology, this might mean starting out by planting hearty ground cover to restore the soil, as was done in Peru.

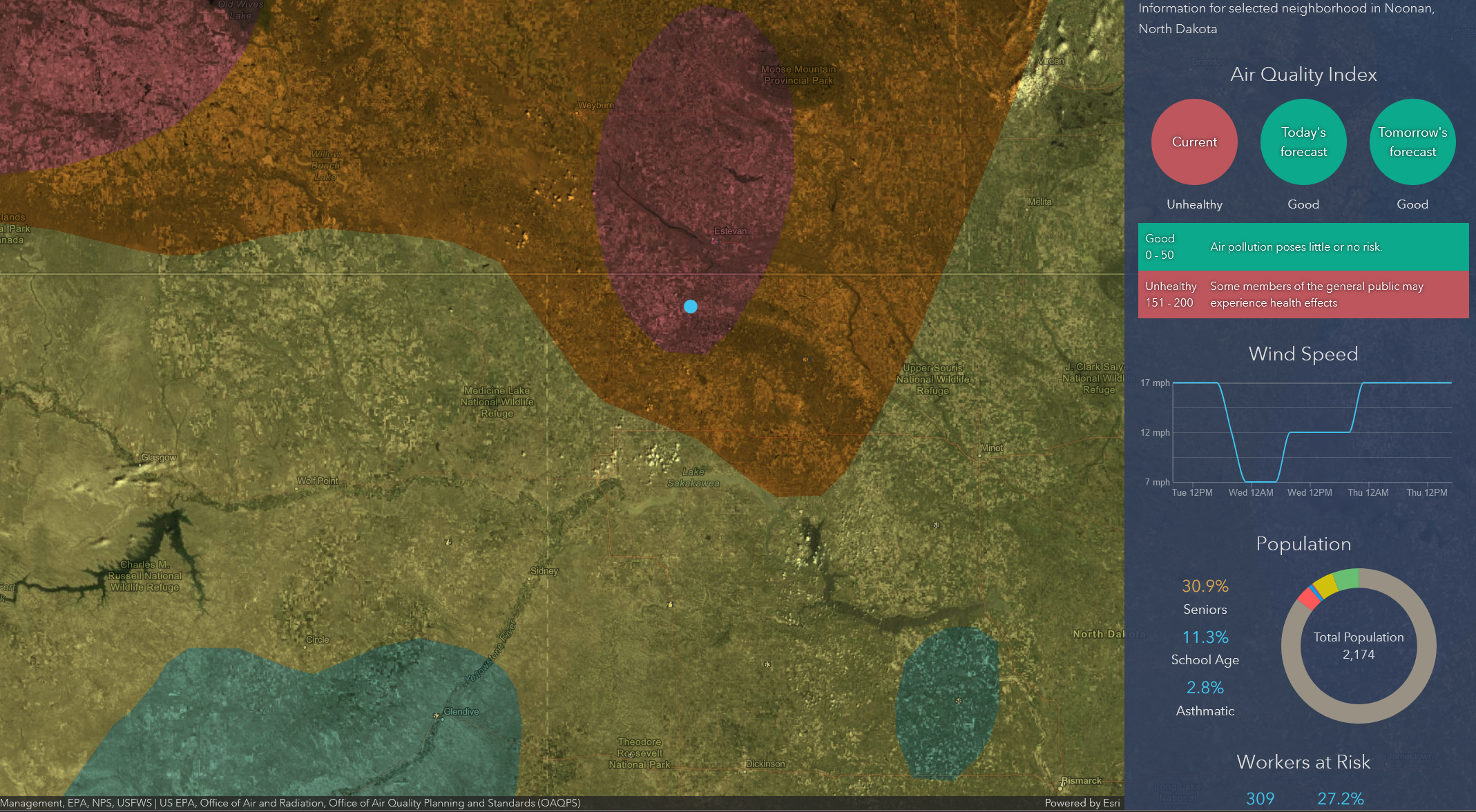

Typically, several large datasets go into this decision-making, from hyperspectral satellite imagery and drone images of the area to ground surveys, to understand the local environment and what’s needed for restoration. “The datasets are very large, and sometimes it’s hard to understand what the relationships are. That’s where the AI comes in,” Fletcher said. Artificial intelligence can also help to create planting maps, considering factors like elevations and water distribution.

The species to be planted determines the size and nature of the seed ball, which must be as small as possible to maximize the payload.

“You start developing your science requirements wrapped around what’s needed for restoration, which leads to your engineering requirements, and then you finally wrap in the operational requirements,” Fletcher said. “You use that typical NASA hardware engineering development pathway. And then you develop the payload once you have all those requirements really understood.”

His launching system is proprietary, but he says it’s something along the lines of a spring-loaded catapult. It can launch 300 seed balls in a minute at an accuracy within about half a yard. He notes that others achieve even greater accuracy at the expense of speed. “My system goes for larger distribution, lower cost by boosting the planting rate.”

Four drones could plant 40 million trees per year, enough to meet the demand from small-scale landholders in most countries, he said.

In its first five years, the company carried out demonstrations in Panama, Peru, and Kenya, planting a total of around 200,000 trees. Much larger projects are getting underway in Peru, Brazil, Indonesia, and the Bahamas, and the company is in discussions with several other potential partners, Fletcher said.

By late 2026, he said, he hopes to have rolled out full business operations in at least two countries. Under the company’s franchise approach, this will mean working with organizations that already understand an area’s ecology and have relationships with the local and federal governments. The company will hire and train local drone operators, technicians, remote sensing analysts, seed ball manufacturers, and managers. A revenue-sharing arrangement incentivizes forest maintenance after the planting is done.

Funding can come from various sources, including carbon credits, governments, foundations, landholders, and others.

Tree planting is often framed as carbon capture, but Fletcher thinks of it more as restoring “ecosystem services,” the many benefits, direct and indirect, that ecosystems provide people. For example, loss of rain forest means less local precipitation. A degraded ecosystem doesn’t support a healthy soil nutrient cycle. All this hurts local agriculture, and the effects are also felt offshore in fisheries, where less water is carrying fewer nutrients to sea, he said. Healthy forests are key to reversing those trends.

“At the end of the day, NASA’s technology has been a centerpiece to helping us develop new technologies to manager our critical resources like fisheries, rivers, and forests,” Fletcher said.

Fletcher poses with the Flying Forests drone he outfitted with a rapid-fire launcher to carpet 25 acres of deforested Peruvian jungle with balls containing the seeds of a hearty legume species. Credit: Beta Earth LLC

Volunteers from the Peruvian Army and Wake Forest University’s Center for Amazonian Scientific Innovation help to handmake thousands of seed balls to be launched by drone across 25 deforested acres in the Amazon jungle in late 2024. Credit: Beta Earth LLC

In June of 2024, volunteers with Flying Forests’ reforestation efforts examine a formerly barren area in the Peruvian rainforest that they sowed with seedballs only the previous November. Now this crop of smooth Crotalaria provides ground cover to allow other native species to take root. Credit: Beta Earth LLC

This oyster toadfish was one of many living specimens flown to space in 1998 as part of NASA’s Neurolab mission, which observed the effects of weightlessness on animals’ central nervous systems. As a NASA employee, Lauren Fletcher helped design the Neurolab platforms that would experiment on various species in space. The Flying Forests founder later applied this experience of tailoring hardware to different biologies when he created drones capable of rapidly firing balls of different plant seeds. Credit: NASA

Volunteers with Flying Forests’ efforts to reforest the Peruvian jungle send up a drone laden with seed balls in December 2024. In an hour and a half, the little aircraft peppered 25 acres of deforested land with 20,000 balls containing the seeds of the hearty smooth Crotalaria plant, along with plant food and materials to deter predators. Credit: Beta Earth LLC