Professional Development Program Gets Bird’s-Eye View of Wineries

NASA Technology

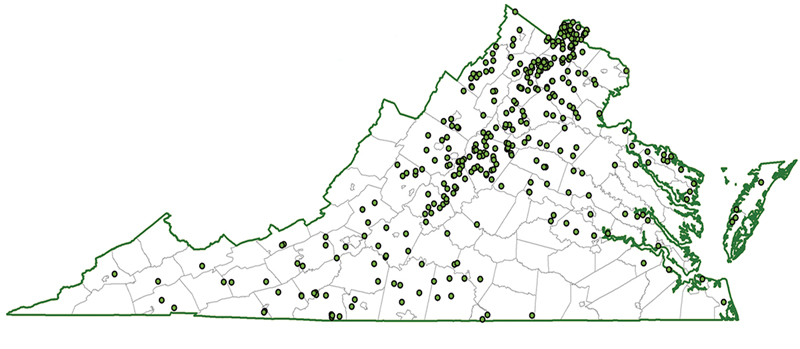

Virginia might not yet rival California when it comes to wine production, but a growing number of wineries and vintners are cropping up across the commonwealth. Hundreds of acres of grapes are planted annually, ranging from sweeter varieties to more traditional chardonnay and cabernet species, and wine growers use detailed maps to keep track of which grapes are growing best across their property.

Ask vintners how many acres they have, and they can give you a number off the top of their heads. But ask where the property lines are, or whether the fields cross into another county, and the answer is less clear. NASA’s Langley Research Center found some researchers to help Virginia and its wine makers understand where grapes are being grown.

Langley houses the National Program Office for NASA’s DEVELOP Program, in which up to 400 students and professionals from across the country annually get the opportunity to build their capacity to work in the science, technology, engineering, and math fields. Participants work on one or more of the approximately 80 environmental and public policy projects the program takes on each year using Earth observations collected from NASA tools.

In 2015, a handful of participants used data and images obtained by the NASA-built Landsat satellites to help identify the boundaries of vineyards across Virginia as a way to help the Virginia Wine Board, based in Richmond, Virginia, better understand where grapes are grown in the commonwealth.

Technology Transfer

DEVELOP has nodes at 12 locations across the United States, including NASA field centers and cooperative locations. Participants are often working toward undergraduate or graduate degrees, or they may be in the work force looking to advance their career or make some sort of transition, says Kent Ross, Langley scientist, national science advisor for DEVELOP, and one of the group’s advisors on this project. The program started in 1998 when student interns at Langley co-authored a research paper on remote sensing capabilities while, at the same time, the Digital Earth Initiative kicked off a project to increase public access to Federal Earth science information. Candidates compete to participate, with a selection rate of about 25 percent, Ross says, with some taking part in more than one research opportunity.

This was, in fact, DEVELOP’s second project with Virginia wines. In an earlier effort, a team partnered with the Virginia Department of Agriculture to examine suitability for siting vineyards across the commonwealth according to current and forecasted temperatures.

The program hit on this next project because the self-reported responses to an annual member survey weren’t providing the Virginia Wine Board with total vineyard acreage at the same level of confidence as previous surveys from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA had stopped providing that kind of data several years prior. “The Wine Board felt the survey they did was pretty successful, but they didn’t have a way to validate the information in a secondary way,” Ross says. “That’s what they were looking to us for.”

The Wine Board provided the results of the survey and vineyard addresses, which the DEVELOP team used as a starting point for investigation.

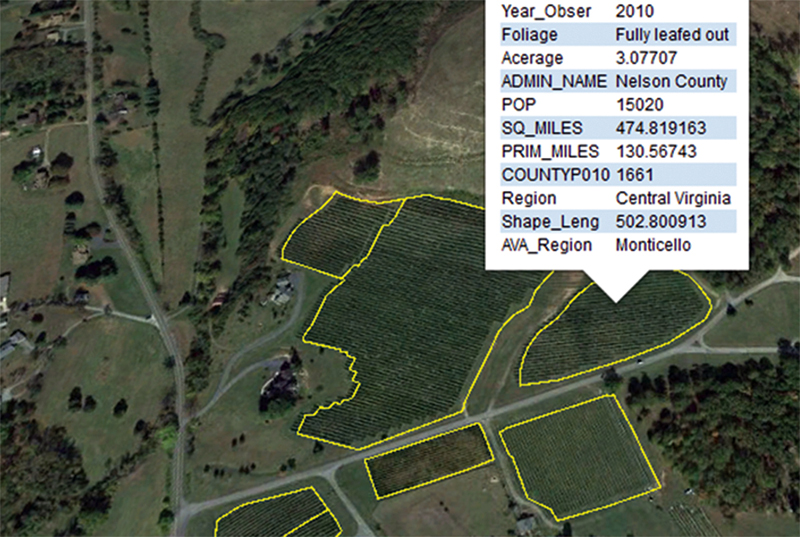

The researchers “carefully and laboriously scanned aerial photos of many square miles of Virginia in the areas where wine production is intense,” Ross says, and they were able to identify field boundaries. “The patterns you can see in the vineyards, especially because of the trellising that’s done for the vines, make them distinctive and allow those fields to stand out from other orchards or crops.” The team was able to verify about 80 percent of the acreage tracked on the surveys, but they also discovered some discrepancies, including the counties in which some of the grapes were grown.

“If winemakers said ‘I have so many acres,’ they wouldn’t say ‘I have so many acres in this county and so many acres in that county,’” explains Annette Boyd, director of the Virginia Wine Board’s marketing office. “We’re getting into an additional level of detail with this data that we just didn’t have with the voluntary data collection. As we go forward, it’ll allow us to really perfect our measurements of Virginia vineyards.”

The team also saw that certain wavelength combinations helped corroborate the presence of mature grapevines but found that an automated approach to classification of grape plots using Landsat imagery would require further research.

Benefits

Figuring out how many acres across a single state are dedicated to growing grapes might not seem like a big deal. But wine is becoming a massive business in Virginia, with 99 percent of the grapes grown there designated for wine production.

And still, Boyd says, consumer demand for Virginia wine is actually outpacing production, so there is currently a push to get more farmers interested in growing grapes and to get landowners to consider growing grapes on land they’re not using. Such a boon would further diversify Virginia’s agricultural economy, historically known for ham, peanuts, and tobacco, while also boosting the profile of wines already made there.

Karen Jackson, Virginia’s secretary of technology, says using satellite data to benefit vintners just makes sense. “Government is not flush with cash, as much as people like to think it is, and we’re not deep of bench when it comes to people. Plus, it’s a resource that tax dollars have already paid for. Why shouldn’t the state leverage those? I think that’s good government.”

Boyd points out that the full potential of using Landsat imagery to help grape growers hasn’t yet been tapped. Future surveys might use the imagery to map pesticide use and to monitor heat, one of the key factors behind the ripening of the fruit. “Those measurements—temperatures, along with soil content and moisture, rainfall, and altitude—will help us in the future to identify which sites are good for growing the crop and which aren’t,” she says. Satellite views can also provide a sufficiently detailed picture that allows farmers to assess the health of individual rows of vines in their fields. Currently, many wineries hire videographers to capture these views using planes, but satellite imagery could provide the same function at a fraction of the cost.

DEVELOP’s use of Landsat and Google Earth data to help pinpoint vineyard locations is “a testament to the fact that technology is being integrated into everything,” says Jackson. “We’re empowering other people to do good things, and that’s what technology is for.”

She adds, “For NASA to have something like the DEVELOP Program that’s available and reachable, I think the biggest problem is that not enough people know about the program. It really has the capability to change industries and move economies along.”

NASA data revealed exactly where wineries were located and also yielded information that could be used to monitor the health of the crops in the future.

This map shows the location of Virginia’s many vineyards, which plant hundreds of acres of grapes annually, almost all used for wine. NASA data helped local government officials take stock of the commonwealth’s wineries and devise strategies for increasing production to meet rising consumer demand.

A vineyard in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains.