Astronaut Life Support for Earth Families

Subheadline

Grow towers for crops and seafood will soon drive self-sustaining shelters

Bart Womack likes to be prepared, and he has found no better resource than NASA. After all, an agency preparing for survival in the frozen void of space is ready for anything.

Spacefarers on a trip to Mars or an extended stay on the Moon won’t be resupplied by missions from Earth, and bringing months’ or years’ worth of supplies would be extremely costly. Instead, NASA has worked for decades to develop a life-support system that functions as a self-replenishing ecology.

At the heart of this work was the Controlled Ecological Life Support System (CELSS) program, which ran for about 25 years, between the late 1970s and early 2000s, with related work continuing today. The goal of CELSS was to create an enclosed biological system that could sustain astronauts indefinitely. It relied especially on plants, which recycle waste into food and oxygen.

Today, the project’s results are helping to move farming indoors and make it more efficient, and they’ve helped Womack’s company build food-production technology that could make families and communities self-sufficient.

Womack’s research to help enable self-reliance for people on Earth brought him to NASA’s plans for deep space missions.

“We started to take the NASA technology, because it had already been designed for maximum efficiency, and to amalgamate it into our designs,” Womack said. He founded Houston-based Eden Grow Systems Inc. in 2017.

CELSS became the starting point for the company’s ultimate goal, the Genesis System, an enclosed habitat that can indefinitely support a family of four off the grid. First, though, the company is marketing parts of the system as they mature. Grow boxes for hobbyists are in the works. And Eden’s first products, six-foot towers that can grow various crops and breed fish or shrimp, started shipping in fall of 2021.

Around that time, the company recruited Gary Stutte, former plant research director from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, who worked on biological life-support systems since he started with the CELSS program in the early 1990s. While Womack had previously reached out for occasional assistance from scientists who worked on CELSS, which was primarily carried out at Kennedy, Stutte is now the company’s in-house director of research and development.

Small Details, Huge Payoffs

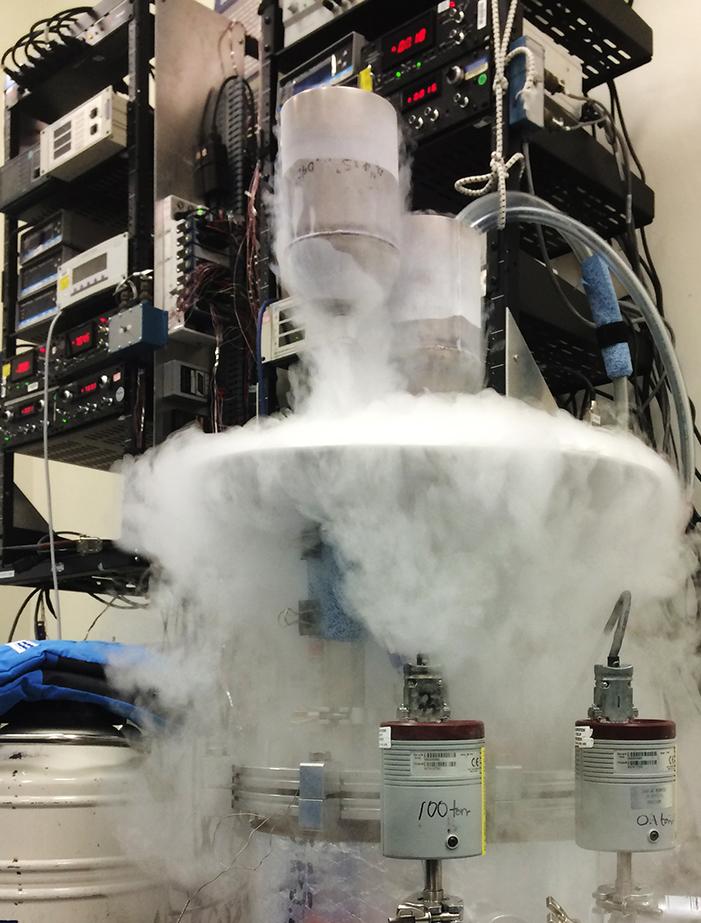

Scientists working on CELSS experimented with basic technology, like LED grow lights, hydroponic and aeroponic growing techniques, and “aquaponics” that would incorporate fish into the system, said Stutte. But they also spent years working out the fine details – identifying the best crops for an indoor environment and the ideal growing conditions for each, and then combining them in a system that would maximize growth and nutritional value while using minimal energy and recycling resources.

Not everything worked, but all the experimentation and results were meticulously and publicly documented. “In a single decade, about 600 technical reports, manuscripts, and other publications came out of that program,” Stutte said, noting that he coauthored around 150 such documents.

In the end, the payoff was substantial, he said. “We were producing yields that far exceeded what was considered feasible.”

Crops like wheat and potatoes, which had hardly been grown indoors, produced yields two or more times the size of outdoor farming records, often in shorter growing periods.

LED lights, safer and more efficient than other lighting, were first commercialized while CELSS was ongoing, and NASA was the first agency to demonstrate their feasibility for plant growth.

The team determined the best temperatures and nutrients for each of about 50 crops, as well as optimal lighting wavelengths, intensities, and durations. They also made systems as automated and user-friendly as possible, because they would be used by astronauts who weren’t plant physiologists and had other jobs.

This emphasis on ease of use and precise “recipes” of lighting, temperature, and nutrients for various crops is central to Eden Grow Systems’ approach.

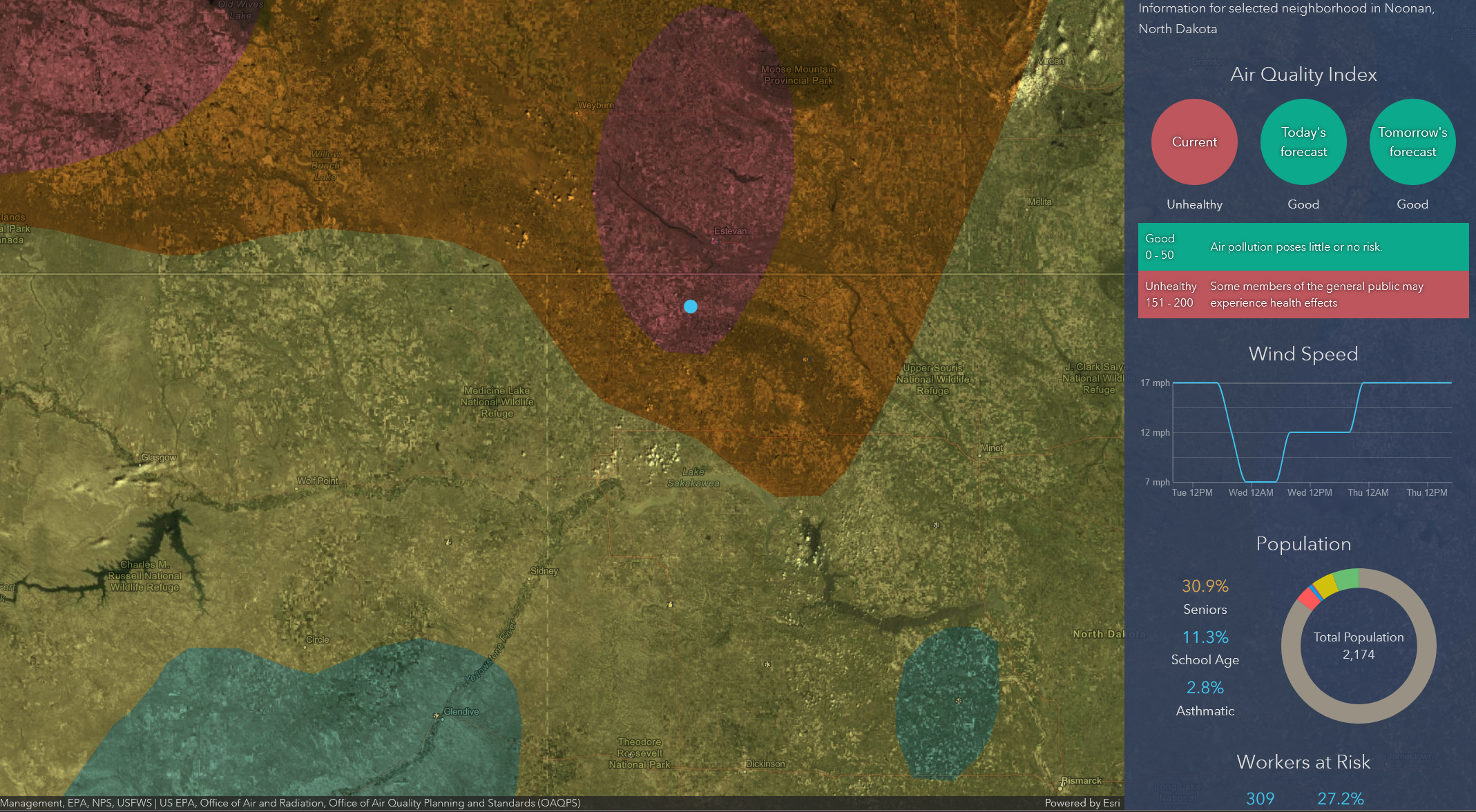

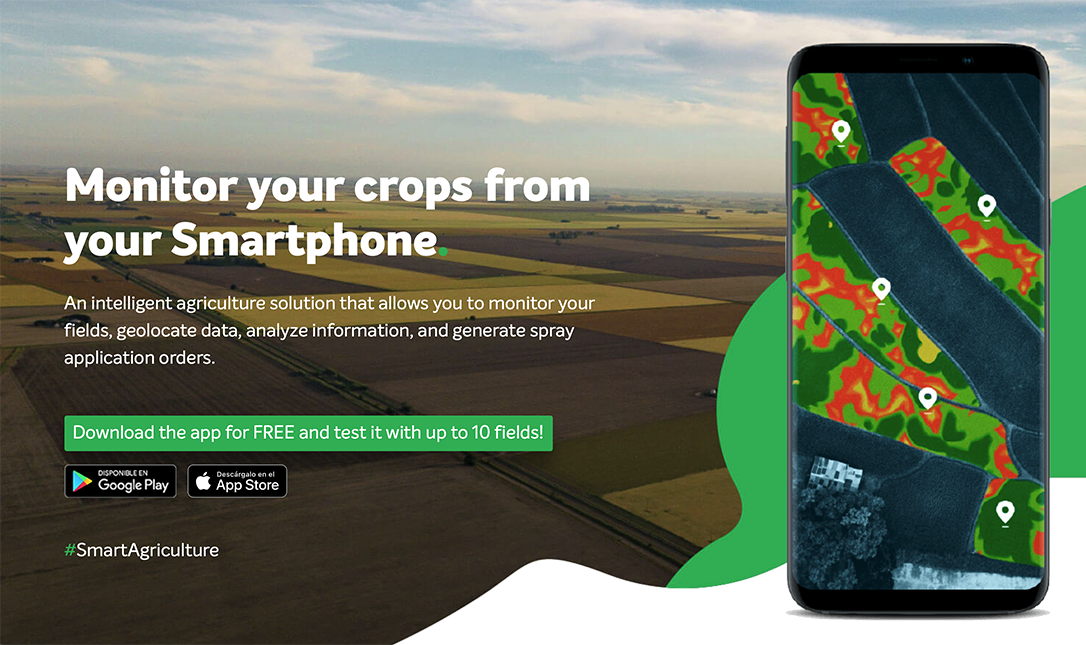

“The biggest secret in the sauce is specific grow profiles for specific plants, which are controlled through our app,” said Womack.

Beyond NASA: Refining Aeroponics and Aquaponics

One reason user-friendliness is so important for Eden’s technology is that its plant nutrient delivery system is based on aeroponics, a delicate technique NASA tried out during CELSS but discarded for use in space, at least for now. Aeroponics nourish plants without soil, by intermittently misting the roots with a nutrient solution. They use a bare minimum of water and nutrients and can support a wide variety of plants.

NASA and many indoor growers have eschewed aeroponics because they can be risky. If misting is disrupted for even a few hours, a whole batch of crops can be lost, said Womack. “Aeroponics is fragile, with a lot of potential points of failure. We identified all of them and came up with novel solutions and backups, so if there’s a failure, you don’t lose your crops.”

Eden’s grow tower customers can also opt for a 60-gallon reservoir for raising fish or shrimp, which provide additional food for the grower and whose waste becomes plant fertilizer. And some plant waste, like leaves and stems humans can’t digest, becomes food for the fish. Because fish and shrimp produce abundant fertilizer, one tower’s fish reservoir can provide nutrients for plants in up to 16 other towers, said Womack.

NASA also explored this technique, known as aquaponics, during the CELSS program but put it on hold for use in space because the fish consumed oxygen and produced carbon dioxide, defeating one purpose of a spacecraft life-support system, said Stutte. In terrestrial applications, however, oxygen isn’t an issue, he noted. “On Earth, aquaponics reduces your reliance on external fertilizer, and you get this biological loop.”

Eden Grow Systems is hardly the first company to capitalize on NASA’s research into growing plants in space. “Those projects laid the framework for an entire indoor agriculture industry,” said Stutte. But others building on these technologies usually use them for either small-scale countertop units or warehouse-sized farming operations, he said, noting that Eden might be the only company applying these lessons to mid-sized operations for a family or community.

Preparing for Anything

Eden is delivering its first towers in various configurations of plant-growth shelves and reservoirs. Womack said early customers include schools and churches, where the towers can bring communities together and teach kids about science and technology.

By the end of 2022, he hopes to ship the first entire Genesis System habitats. These will run on power harvested from wind, sunlight, and biogas, and they’ll be outfitted to feed a family. The U.S. Air Force has expressed interest in uses at military bases. Womack noted that the habitats would be useful at remote outposts or for disaster or famine response, not to mention space applications (he hopes NASA will one day be a customer).

“I see us not as a next-generation farming company but as a life-support company,” Womack said. “My vision is that every home on Earth has a life-support system.”

If that’s a different way to consider agriculture, so was NASA’s approach to growing food. “NASA’s investment in plant growth has been miniscule compared to the agency’s total budget – on the order of a rounding error,” said Stutte. “But its impacts are fundamentally changing the way food is being grown.”

NASA researchers Neil Yorio and Lisa Ruffe inspect lettuce inside NASA’s Biomass Production Chamber at Kennedy Space Center in 1991. For more than 20 years, NASA used the chamber to run experiments on crop growth in support of the Controlled Ecological Life Support System program. Credit: NASA

NASA plant scientist Gary Stutte holds two plant experiment modules that flew on the last space shuttle mission in 2011. After retiring, Stutte joined Eden Grow Systems as director of research and development. Credit: NASA

Bart Womack, founder and CEO of Eden Grow Systems, trims a plant in one of the company’s grow towers. Credit: Eden Grow Systems Inc.

Eden Grow Systems technician Eli Long checks on plants in one of the company’s grow towers. Credit: Eden Grow Systems Inc.