From Pluto to Farms and Pharmaceuticals

Subheadline

Water-finding filter for dwarf planet helps out on Earth

A NASA spacecraft currently flying through the Kuiper Belt is carrying technology that is now supporting pharmaceutical manufacturing and other applications on Earth.

A linear variable filter, or LVF, from Chandler, Arizona-based VIAVI Solutions Inc. has been refined over multiple NASA missions. VIAVI incorporates similar LVFs in its MicroNIR family of miniature spectrometers, which are used in pharmaceutical manufacturing and agriculture.

VIAVI’s linear variable filter is flying on NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, which launched in 2006, reached Pluto in 2015, and continues to explore the Kuiper Belt, a region of icy objects and dwarf planets in the far reaches of our solar system.

“Before the NASA work, we had early prototypes of spectrometers utilizing our LVF technology, but they weren’t as well engineered as the MicroNIR is,” said Michael Klimek, who manages spectral sensing research and development for VIAVI in California.

“At the time, spectrometers were bulky, benchtop instruments,” he said. “By leveraging our LVF technology, we were able to shrink the spectrometer to the size of a golf ball and optimize the power consumption of the device, a major innovation that has opened new applications and markets for spectroscopy.”

Small and Light for Pluto

NASA uses spectroscopy to determine what planets and their atmospheres are made of by analyzing how light in the visible and non-visible ranges interacts with matter. While there are various ways to outfit a spectrometer, the linear variable filter has advantages, including size, simplicity, and the ability to adapt to different tasks.

Dennis Reuter led the team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, that developed the New Horizons instrument. That included the Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array, or LEISA, which carries the VIAVI filter. He said the simple assembly of LVF spectroscopy was an advantage.

“You just put this filter over the detector, and there’s your spectrometer,” he said.

Also, the filter can be designed to detect narrow spectral bands without picking up the bands in between, limiting the information — and, therefore, the data transmission needs — to what is useful, another space-saving feature.

“If you’re going to Pluto, you want things to be light and small,” Reuter said. “You can design this thing specifically for what you’re looking at, and that also means you end up with less data, and smaller data volumes coming down, which makes a big difference.”

By the time the New Horizons mission came around, NASA had already worked with VIAVI on a linear variable filter for a spectroscopy instrument on the Earth Observing-1 satellite, which launched in 2000.

“We had already had some back-and-forth with them, and the filter improved every time,” Rueter said.

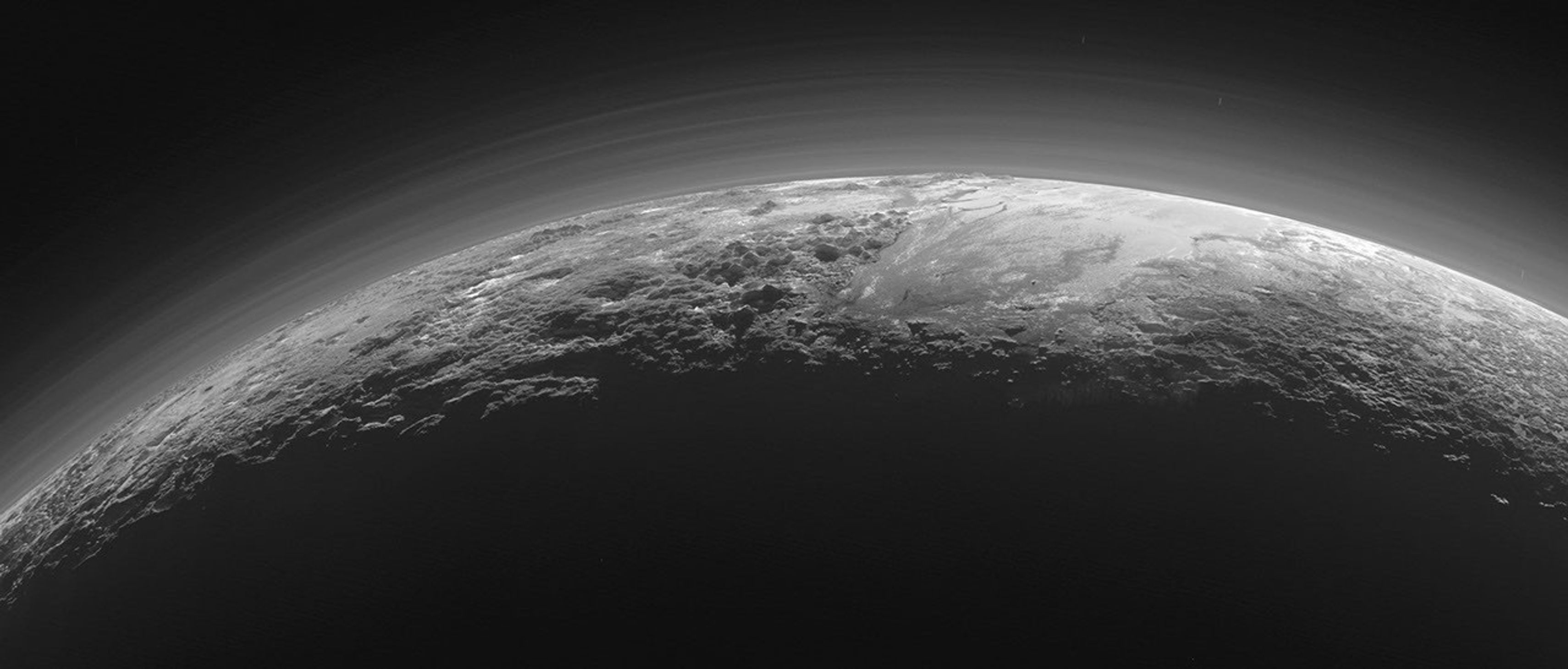

New Horizons in 2015 began sending back data from Pluto, including surprising images revealing previously undetected water ice and nitrogen ice, in addition to the methane ice scientists knew about. In 2016 Reuter and his team were finalists for a Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medal for their work on the project.

The spacecraft is currently twice as far from Earth as Pluto and still making discoveries, though light is limited so far from the Sun.

VIAVI has continued to develop the filter for new NASA missions, such as Lucy, which launched in 2021 and will carry out surveys of the Trojan asteroids in Jupiter’s orbit from 2027 to 2033, and the Europa Clipper, which launched in 2024 and is scheduled to arrive at Jupiter’s moon Europa in 2030. The filter is also on the Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer or SPHEREx, an astrophysics mission that launched in 2025 and plans to spend the next two years collecting data on the full sky, including hundreds of millions galaxies and more than 100 million stars in the Milky Way to explore the origins of the universe.

Robust and Repeatable

Some of the same features that made VIAVI’s linear variable filter attractive for a deep space mission also benefit terrestrial users of the MicroNIR family of miniature spectrometers.

The filter is monolithic, meaning there are no moving parts. “That makes it very robust and highly repeatable,” VIAVI’s Klimek said. “And, what’s becoming more and more important, it has a very low unit-to-unit variability.”

Initially, VIAVI focused on the device, relying on customers to build their own software models to analyze the raw data for their particular purposes. But the company found it could expand its customer base vastly by offering more assistance with data analysis.

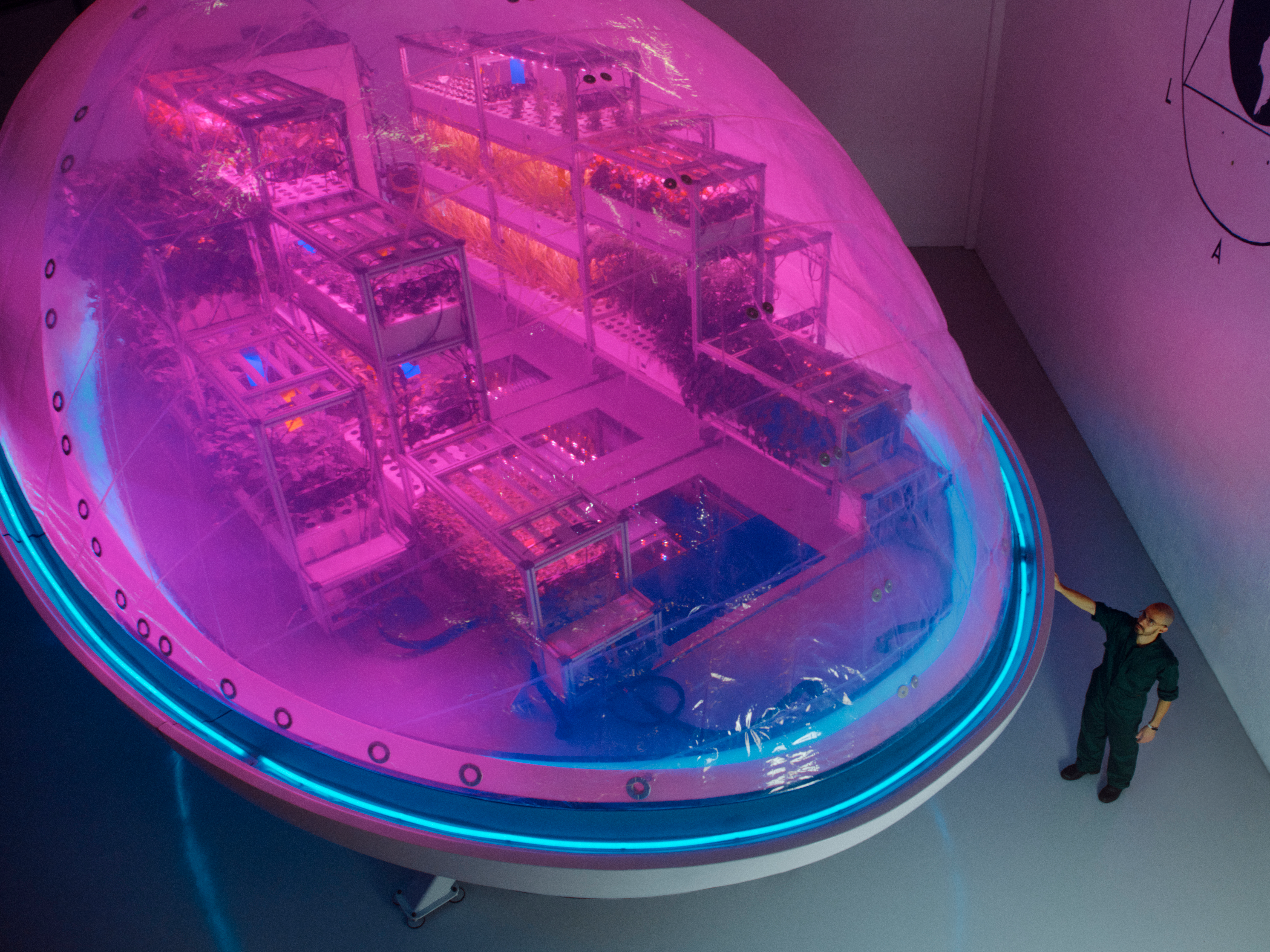

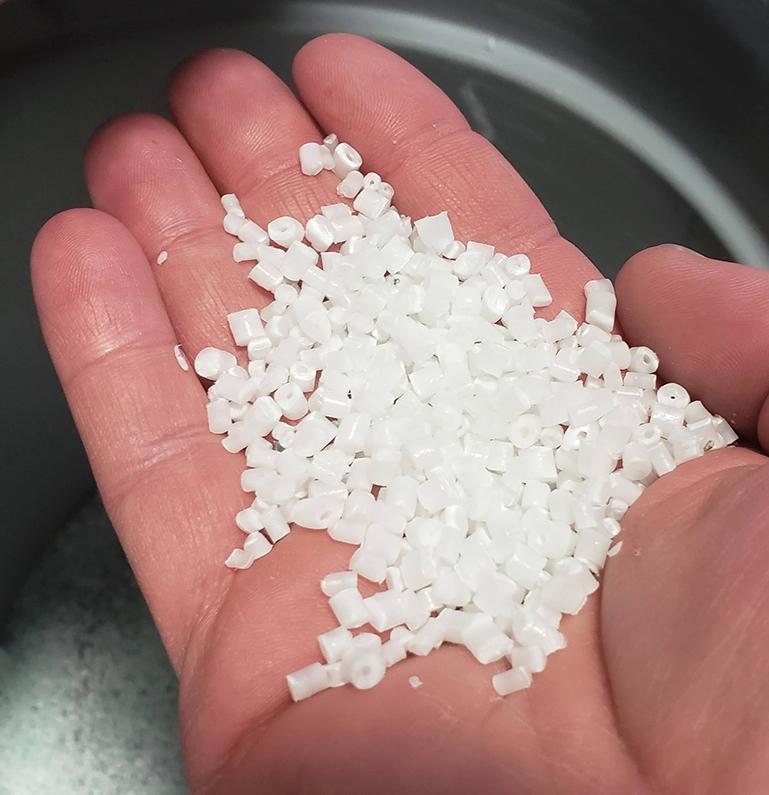

VIAVI is currently helping agricultural customers use the handheld version of the MicroNIR to determine the best harvest times. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, VIAVI’s spectrometers support blend and content uniformity. The MicroNIR also helps food producers detect fraudulent foodstuffs, grade produce on location, and assess key attributes such as moisture, fat, and protein content.

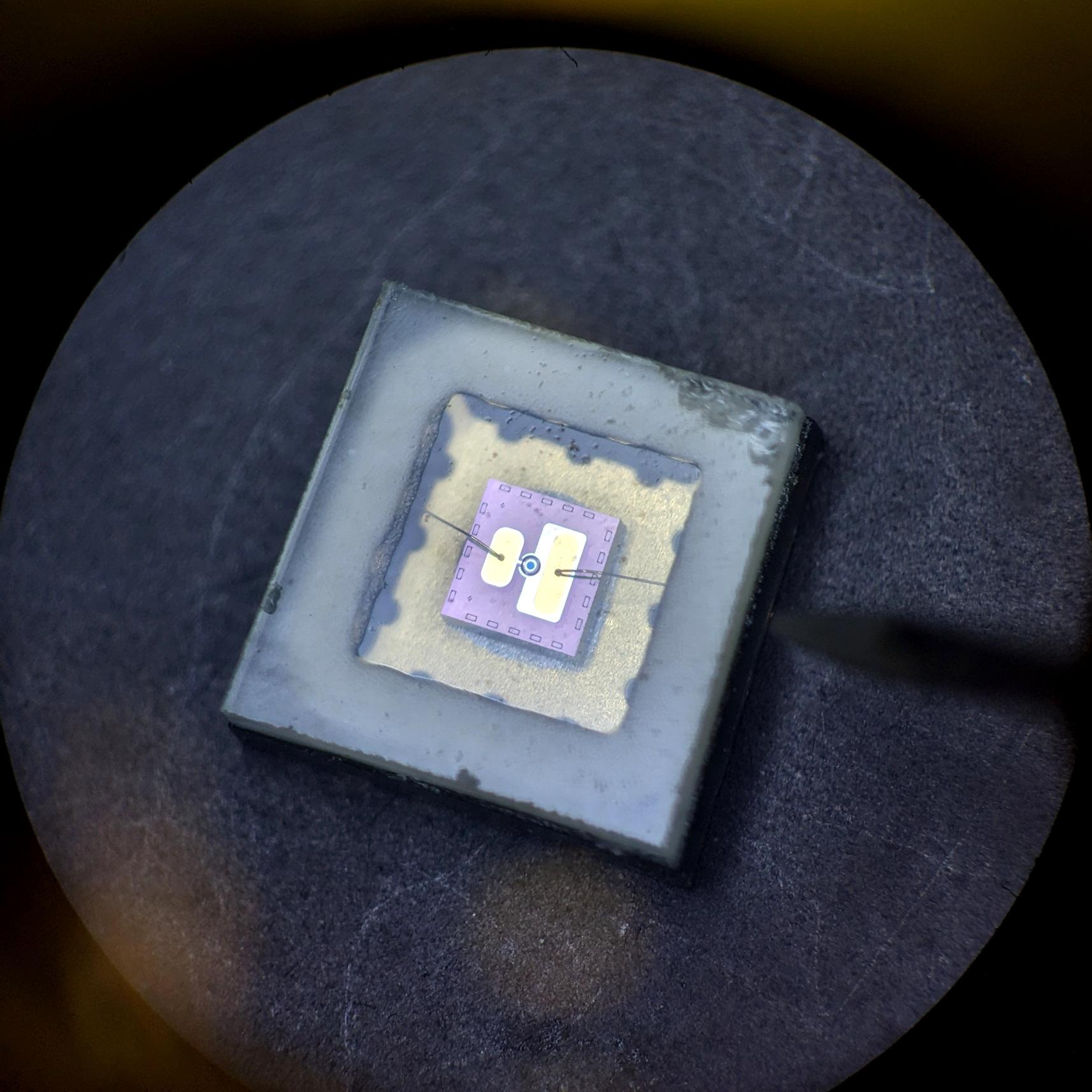

The same filter technology that enables NASA to identify what planets are made of lies at the heart of VIAVI Solutions’ Earth-based handheld spectrometers, one of which is pictured here analyzing ingredients in a food production setting. Credit: VIAVI Solutions Inc.

Pluto images and data from the New Horizons spacecraft determined the dwarf planet’s composition. They were possible because of a spectrometer that included a linear variable filter from VIAVI Solutions. Credit: NASA