Forecasting Saharan Dust to Minimize Health Risks

Subheadline

NASA-funded system uses satellite data to predict timing and severity of African dust storms in the Caribbean

Last summer, wind carried nearly 24 tons of dust from the Sahara Desert in Africa across the Atlantic Ocean, to North and South America, hitting islands in the Caribbean Sea especially hard.

It was one of the largest Saharan dust storms on record, and it came in the middle of the global pandemic. An early warning system for African dust was developed with NASA funding and put in place just days before the event. Through this tool, for the first time, citizens across Puerto Rico received advance notice that the dust storm was coming.

“We were monitoring a couple of different NASA models and satellite images,” said Pablo Méndez-Lázaro, an associate professor at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus in San Juan, who led development of the warning system.

“As soon as we saw the dust storm, we started communicating the news,” he said. “We got in contact with corresponding government agencies and collaborating medical doctors.”

Saharan dust clouds make this journey every year, helpfully fertilizing soil with phosphorus and other nutrients. The right amount of dust feeds Caribbean coral, but too much can cause algae overgrowth. It can also irritate people’s eyes, ears, noses, and throats with fine particles of silica and other minerals that can infiltrate lung tissue, aggravate sensitivities, and reduce visibility.

“During the summer of 2020, as in many other places, we were also struggling with COVID-19,” Méndez-Lázaro said, “and COVID-19 is a respiratory virus. We were very concerned with how the dust could exacerbate the symptoms.”

Early Warning, Better Preparation

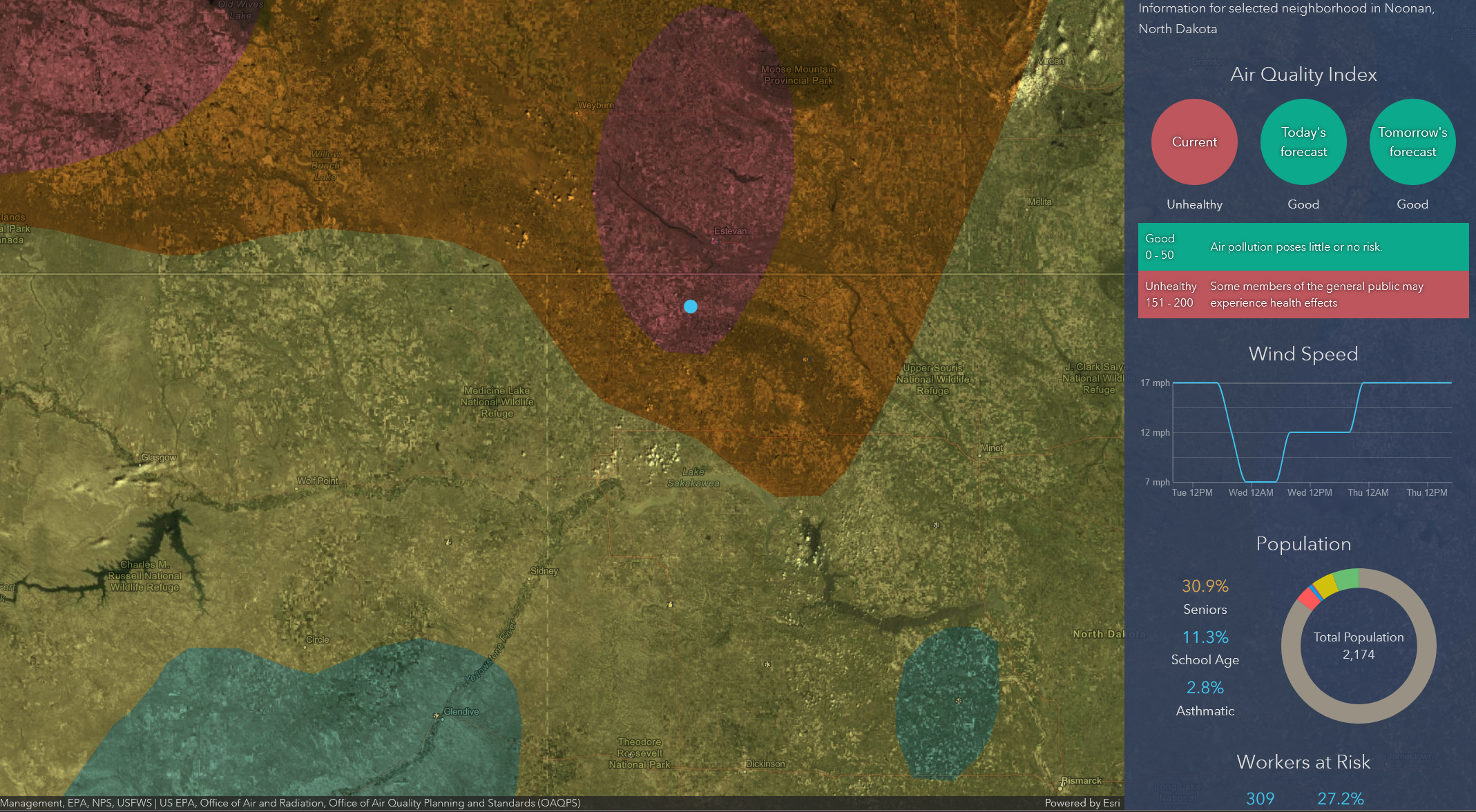

The Saharan dust warning system involves monitoring satellite data, gathering samples, and alerting government agencies and the public, giving people time to prepare.

The 2020 dust storm, nicknamed Godzilla, was so big that astronauts on the International Space Station could see it.

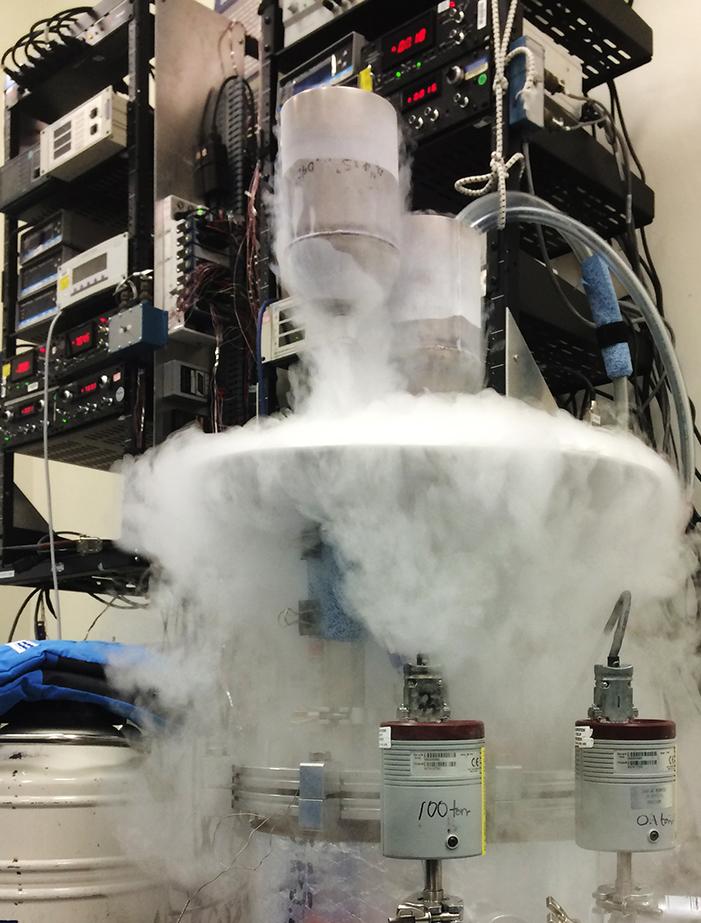

Méndez-Lázaro and his team use an array of NASA tools and sensors to track aerosols – which can include liquids, gases, bacteria, viruses, and volcanic ashes, in addition to dust – mostly with NASA’s Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite, or VIIRS, onboard the Suomi-NPP (National Polar-Orbiting Partnership) satellite.

The VIIRS instrument enables researchers to determine aerosol optical depth, an indicator of the amount of aerosols in the atmosphere.

“It could be a bunch of different things, so the satellite information is not enough to know what kind of aerosol is up there,” Méndez-Lázaro says. “But because of the trajectory of the dust cloud, you know where it’s coming from, and from the ground-based sampling, you know where it was born.”

The additional path and origin information enables scientists to confirm that a cloud is, in fact, Saharan dust, which can help them predict its effects.

Several days before the 2020 storm, Méndez-Lázaro’s team held a Facebook Live event with one of Puerto Rico’s top meteorologists, Ada Monzón, reaching an estimated 300,000 viewers. Méndez-Lázaro also spoke about the hazardous atmospheric conditions on another Facebook Live broadcast by the National Weather Service – San Juan.

Monzón and other meteorologists included the information in their forecasts, so the public and especially vulnerable groups – including the elderly, children under 5, pregnant women, and people with asthma or other respiratory or dermatological issues – could take precautions and avoid being outside.

Méndez-Lázaro and his team also provided visualizations through a tool that they plan to make public-facing. Based on the warnings, the Puerto Rico Department of Health Office issued public health recommendations. The advance warning from the satellite data also enabled the system’s ground samplers to prepare to quickly analyze and characterize the dust, which caused two days of unhealthy air conditions in Puerto Rico.

Better understanding of the dust can help doctors treat patients suffering from its health effects, especially if the dust is carrying pathogens, and it enables the researchers to retrospectively analyze the initial satellite data for possible improvements in future forecasts.

Earth Observations on Earth

Méndez-Lázaro and his team developed the warning system with funding from a three-year NASA Applied Sciences grant awarded in 2019. All proposals were peer reviewed.

By the time the storm came in 2020, an early version of the warning system was in place for Puerto Rico. Méndez-Lázaro and his colleagues have been working to expand it to the U.S. Virgin Islands as well.

The team is currently establishing a sustainable partnership with CARICOOS, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Caribbean Coastal Ocean Observing System, to keep the system in place after the NASA funding ends.

Méndez-Lázaro received additional NASA funding in 2020 to investigate how the Saharan dust plumes and other environmental factors affect the spread and severity of COVID-19.

“We were concerned that people already struggling with the virus could get worse and their symptoms more severe because African dust is another aggravation to the pulmonary system,” Méndez-Lázaro said. His team continues to analyze data and plans to report preliminary findings on this issue later in the near future.

John Haynes, who manages Health and Air Quality applications in the Applied Sciences Program in the Earth Science Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said Méndez-Lázaro’s work is a perfect example of his program’s mission.

“Our mandate is to discover and demonstrate innovative and practical uses of Earth observations,” said Haynes, who served as the NASA-side technical officer on both projects.

Terabytes of Earth data are downloaded every day from NASA’s constellation of Earth-observing satellites. These data are used to answer basic scientific questions about how Earth systems are changing. Then, NASA’s Applied Sciences Program aims to get that information into the hands of people who make forecasting and policy decisions, so those decisions can be quicker or better.

“Pablo and his team are not only harnessing optical-depth data from VIIRS, but also ground observations,” Haynes said. “They’re assembling that information and providing it to other agencies in useful formats so they are able to make better decisions when these dust storms are forecast to occur.”

Aerosols in the Saharan dust plume from June 15 to 25, 2020, created from the Suomi NPP OMPS aerosol index. Scientists at the University of Puerto Rico use an array of NASA tools and sensors to track aerosols – which can include liquids, gases, bacteria, viruses, and volcanic ashes, in addition to dust – and warn people on the island when the air quality will be bad. Credit: NASA/NOAA, Colin Seftor

The normally blue skies above the Caribbean isle of Dominica (bottom) turned brown (top) in June 2020 when that year's massive Saharan dust cloud arrived. Plumes like these originate in Africa each year and travel across the Atlantic Ocean, with impacts felt across the Caribbean and all the way to the Amazon rain forest. Credit: Getty Images

Astronaut Doug Hurley saw the 2020 Saharan dust plume from the International Space Station. He snapped and tweeted this picture. Credit: NASA