NASA ‘Arms’ Astronauts, Industry with Robotic Intelligence

Subheadline

To free up astronauts, NASA tackles complexity of controlling robotic arms

Being an astronaut isn’t always glamorous.

Crewmembers on the space station spend about a third of their time just hauling in cargo from resupply capsules and carrying trash bags back out, said Shaun Azimi, who leads the Dexterous Robotics team at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. And that’s with a full-time crew of seven.

As NASA plans extended astronaut stays on and around the Moon in the later Artemis missions, the agency wants robots to take over some of these menial jobs, freeing up crewmembers to do more of the science and exploration they’re there for. The problem is, while robots in science fiction can often pass for human, developing real-world robots — which would more likely resemble mobile six-jointed arms — to carry out even the simplest human tasks is exceedingly complicated.

“Robotic manipulation historically is like a big arm in a factory moving the chassis of a car from one conveyor belt to another,” said Ezra Brooks, principal software engineer at PickNik Inc., noting that no intelligence is needed to repeat this preprogrammed set of actions over and over.

Getting a robot to recognize an object in an unstructured environment, approach it, and carry out some operation with it is an entirely different and far more difficult job. This is the challenge Boulder, Colorado-based PickNik is overcoming, with help from the space agency.

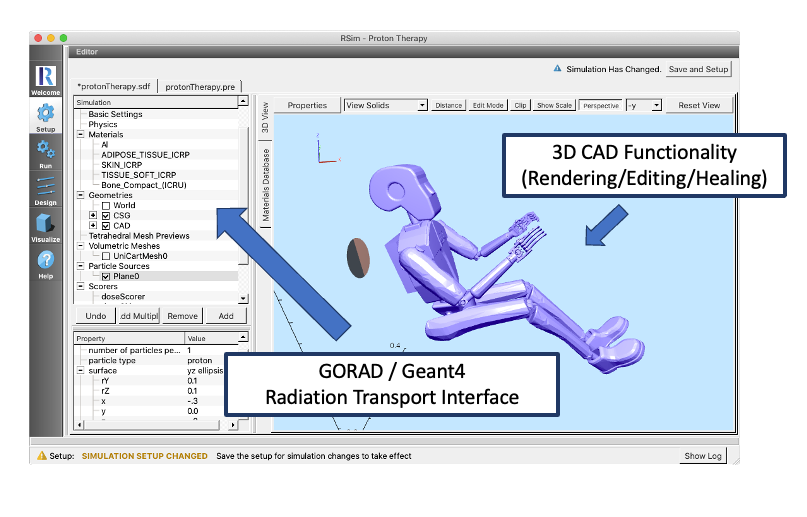

For instance, the company worked with roboticists at Johnson to prove out software that enabled a robot to recognize a hatch on a spacecraft — including its latch, handle, and hinges — then turn the latch, grasp the handle, and open the door.

Just planning the motion from a given starting configuration of the joints in a robot arm to an ending configuration that sets it up for the next action “takes some very clever math and a lot of CPU horsepower,” Brooks said. “Then once you’re actually executing that trajectory, the software is telling the robot all of the minuscule movements it needs to make. Maybe upwards of 1,000 times a second, it’s sending commands saying, move this joint at this velocity or move to this slightly different position.” A force feedback algorithm lets the robot know when it’s grasped the latch, and a control algorithm determines how much force the robot uses to turn it.

While much work remains to be done to prepare robots for lunar operations, software PickNik developed with the help of NASA is already finding applications on Earth.

Robotic Baggage Handlers

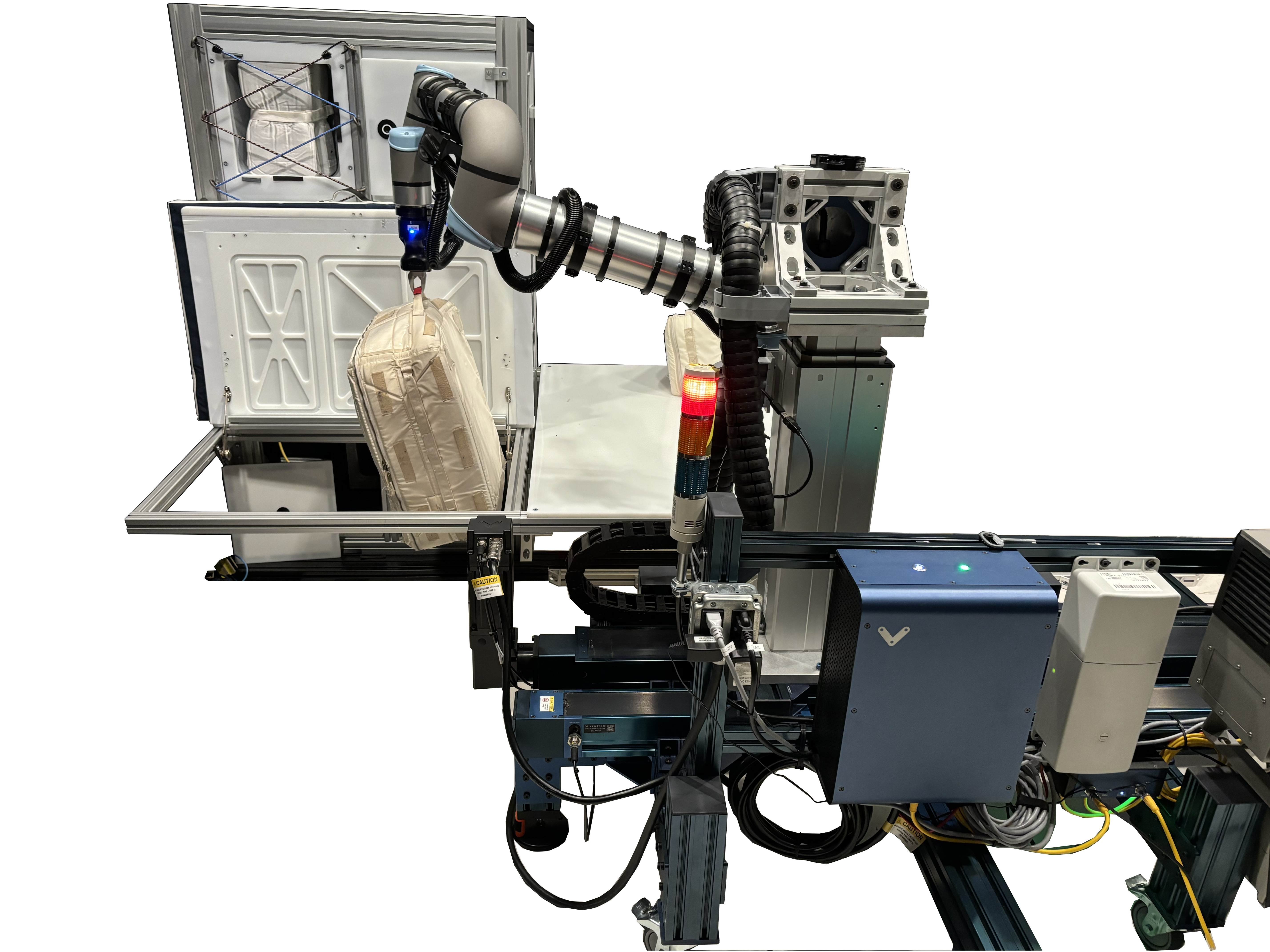

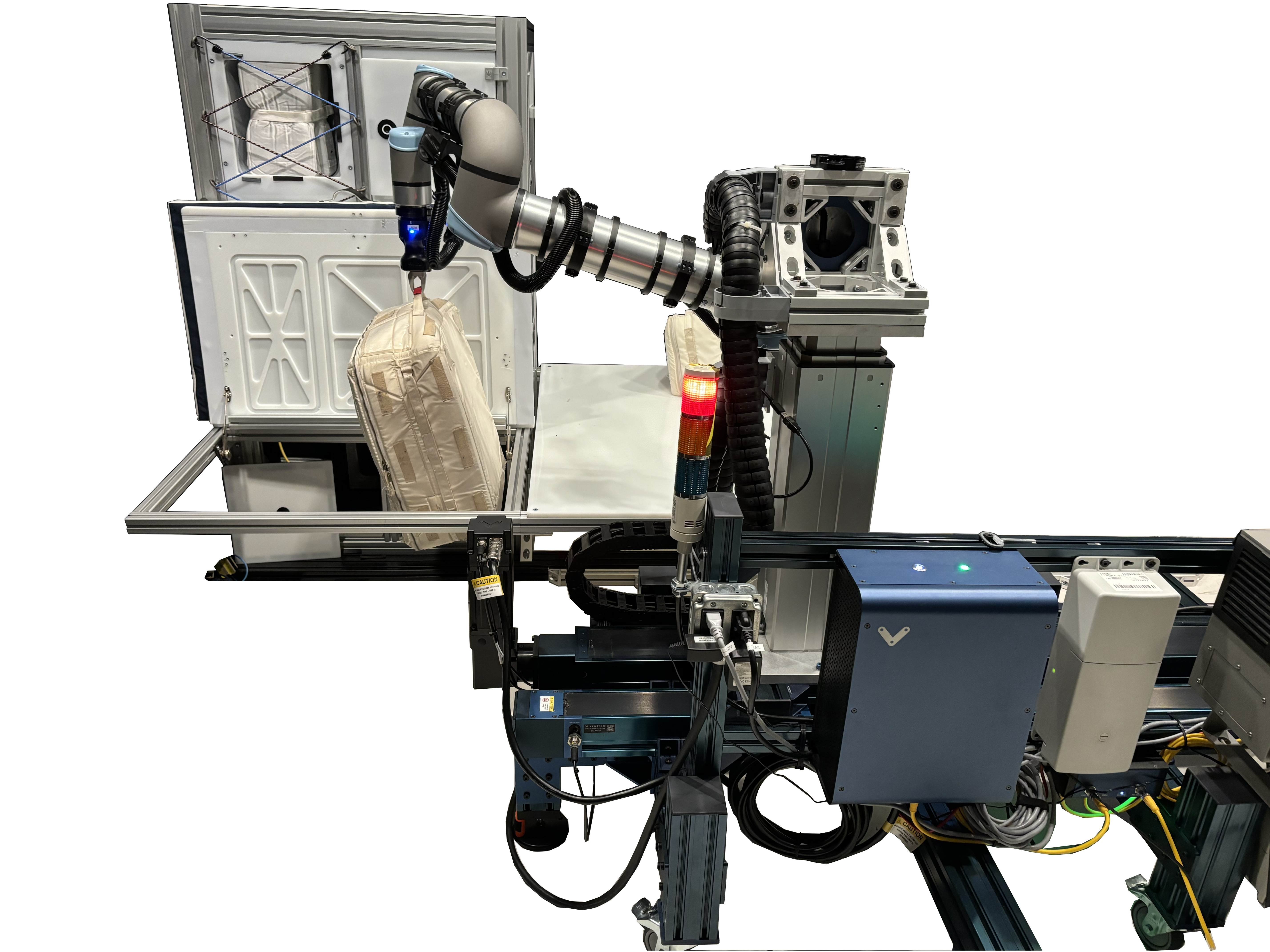

The work at Johnson, funded under the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, was carried out in the center’s new Integrated Mobile Evaluation Testbed for Robotics Operations (iMETRO). There, the team also proved the software’s ability to make the arm lift cargo transfer bags of the sort used on the International Space Station in and out of the hatch and a storage bin, in anticipation of future robots’ Artemis assignments.

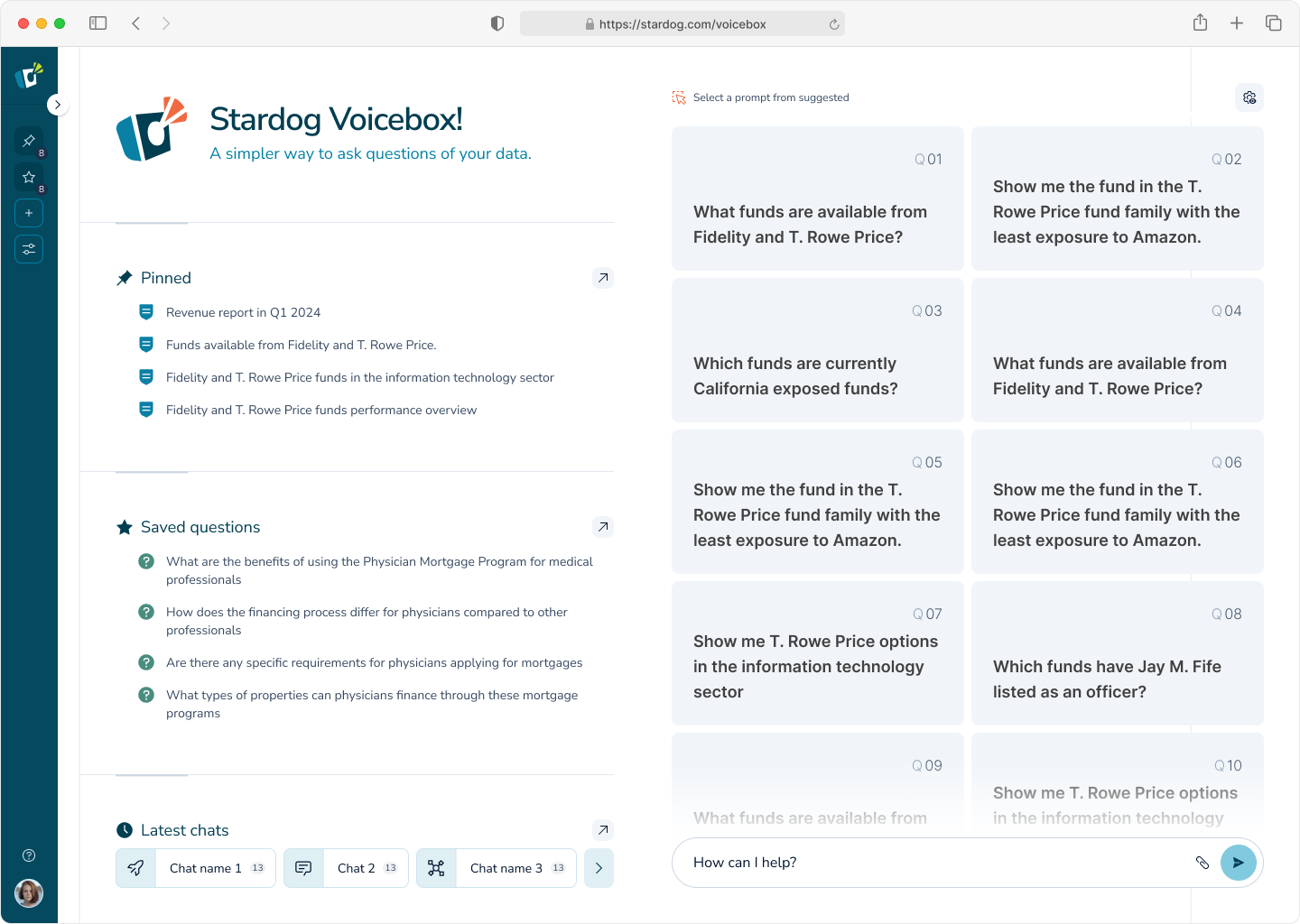

The software PickNik tested with Azimi, now known as MoveIt Pro, had been developed under SBIR funding from NASA and the Space Force, and further NASA SBIR contracts have helped refine its user interface and improve its autonomy and ability to recover from failure.

Early Artemis missions will be short, but eventually, crews of four or so might spend one month per year on the Moon and in a space station in lunar orbit, called Gateway. During the other 11 months, Azimi said, robots could load and unload supplies and carry out simple inspection and maintenance work, allowing the next crew to make the most of its stay. “I like to see it as a way to maximize the value of the money we spend on getting humans to the lunar surface,” he said.

He noted that the same robots could serve similar roles on commercial space stations that a handful of companies are now building for low Earth orbit, which also would likely only be crewed part-time.

For now, Azimi said, PickNik is building a commercial customer base on Earth, which helps fund product development and make it sustainable. “So our development through NASA SBIRs focuses on the gaps between that terrestrial use case and the in-space use case.” For example, inconsistent communication between Earth and the Moon will require more independent robots. And the ability to remotely fix any problems that arise will be much more important when human operators are 240,000 miles away. But all of these capabilities come in handy on Earth too.

Brooks said the 35-person company might not have developed a commercial product without early funding from NASA. In robotics, he said, “you have to do years and years of research and iterative development on trying to refine algorithms and doing serious science to get to a point where you even would have a distinct product you could sell.” NASA funded much of that foundational work.

And, he said, it helps to be working with one of the world’s premier robotics organizations. “Working with NASA is really rewarding from the perspective of being able to dive into the deep end of really difficult problems that almost no one else is running into yet.”

In fact, Brooks ran up against some of those problems as a NASA contractor working on the agency’s On-Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing 1 mission, an ambitious robotics project that ended up cancelled a couple of years after he left for PickNik. He said the work helped him foresee and address challenges the MoveIt team would come up against.

Automated Housekeeping, from Restrooms to the Moon

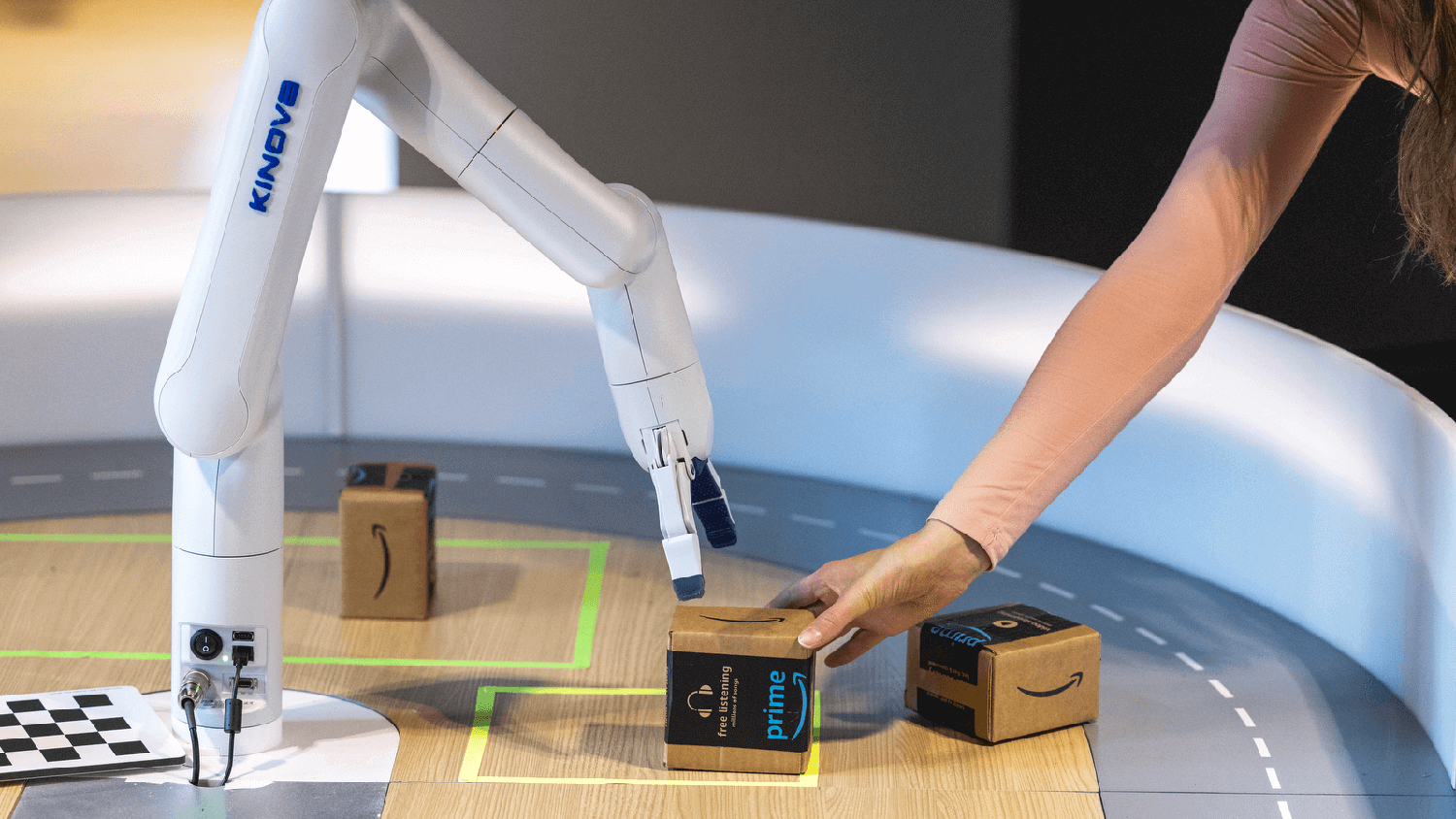

All of the software development funded by NASA has already been folded into MoveIt Pro, the company’s flagship product, Brooks said. Released in 2023, the software has found a significant customer base. BMW is using it to bring more intelligence to its robotic assembly lines, and it automates robotic arm demonstrations in the lobbies of two Amazon Web Services learning centers.

A company called Lightspeed is using MoveIt Pro to program huge robotic arms that build “panels” of walls, roofs, and floors in an attempt to address the nationwide shortage of affordable housing. And PickNik customized the software to help Hivebotics of Singapore automate its flagship product, a restroom-cleaning robot named Abluo.

For MoveIt Pro to one day automate robots in space, though, Brooks said engineers and space agencies will need to do a lot of work to build confidence in robotic intelligence for space missions. “It’s far more complicated than really any other software that’s ever been flown to space.”

But Azimi said the payoff will be worth the effort. Robots capable of logistical work could probably do facility maintenance and even keep science experiments running while the crew is away, he said. “Anything robots can do in those 11 months, you’re ahead of where you would be if you didn’t have that capability at all.”

PickNik’s MoveIt Pro, developed in part with funding and help from NASA, automates robotic arm demonstrations in the lobbies of two Amazon Web Services learning centers. Credit: PickNik Inc.

PickNik’s MoveIt Pro software enables a single Rapid 3PRO, a two-armed industrial robot from Rapid Robotics, to perform dozens of different tasks, and new capabilities can be added quickly. Credit: PickNik Inc.

Hivebotics in Singapore is using a custom version of MoveIt Pro to automate its flagship product, a restroom-cleaning robot named Abluo. Credit: PickNik Inc.

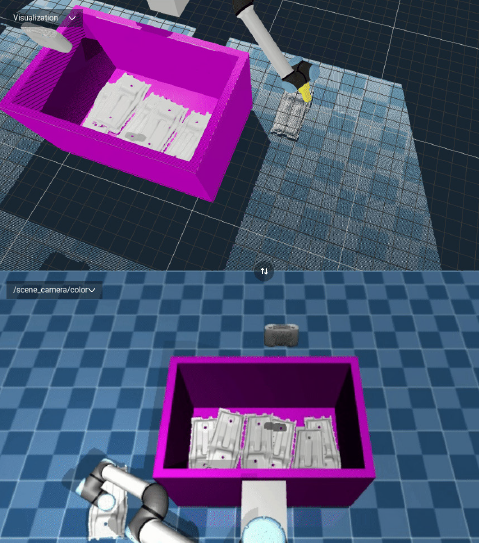

The user interface for PickNik Robotics’ MoveIt Pro robotic control software shows work the company did with automaker BMW to make assembly line robots more capable of dealing with unexpected situations. Credit: PickNik Inc.

In the Integrated Mobile Evaluation Testbed for Robotics Operations facility at Johnson Space Center, PickNik robotic control software proved its prowess in tasks like passing cargo transfer bags through a hatch and placing them in storage bins, in anticipation of work NASA would like robots to carry out during the later Artemis missions. Credit: NASA