Beat the ‘Heet’ at 400,000 Feet

Subheadline

NASA funding helps high-tech insulation take flight

How does a space plane stand up to extreme heat that builds up when it’s traveling at several times the speed of sound?

This question is the origin of Steve Miller’s entire career.

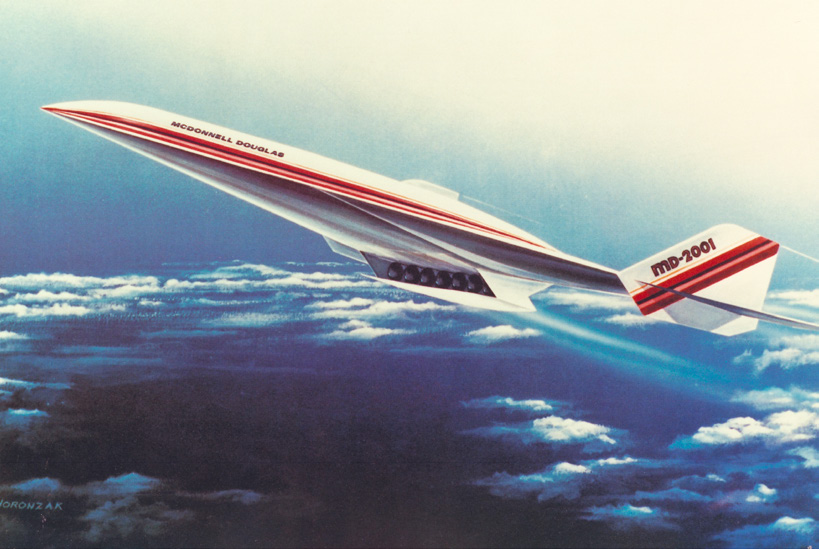

In the 1980s, the National Aero-Space Plane project was intended to be the future of spaceflight, and potentially air travel. In a State of the Union speech, Ronald Reagan promised it would enable passengers to rocket from Washington to Tokyo in two hours. To support this effort, NASA requested Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) proposals for the required technologies.

“I’d met some researchers who’d been working on thermal protection systems for the space shuttle, and they invited me to submit an SBIR proposal to collaborate with them,” Miller said.

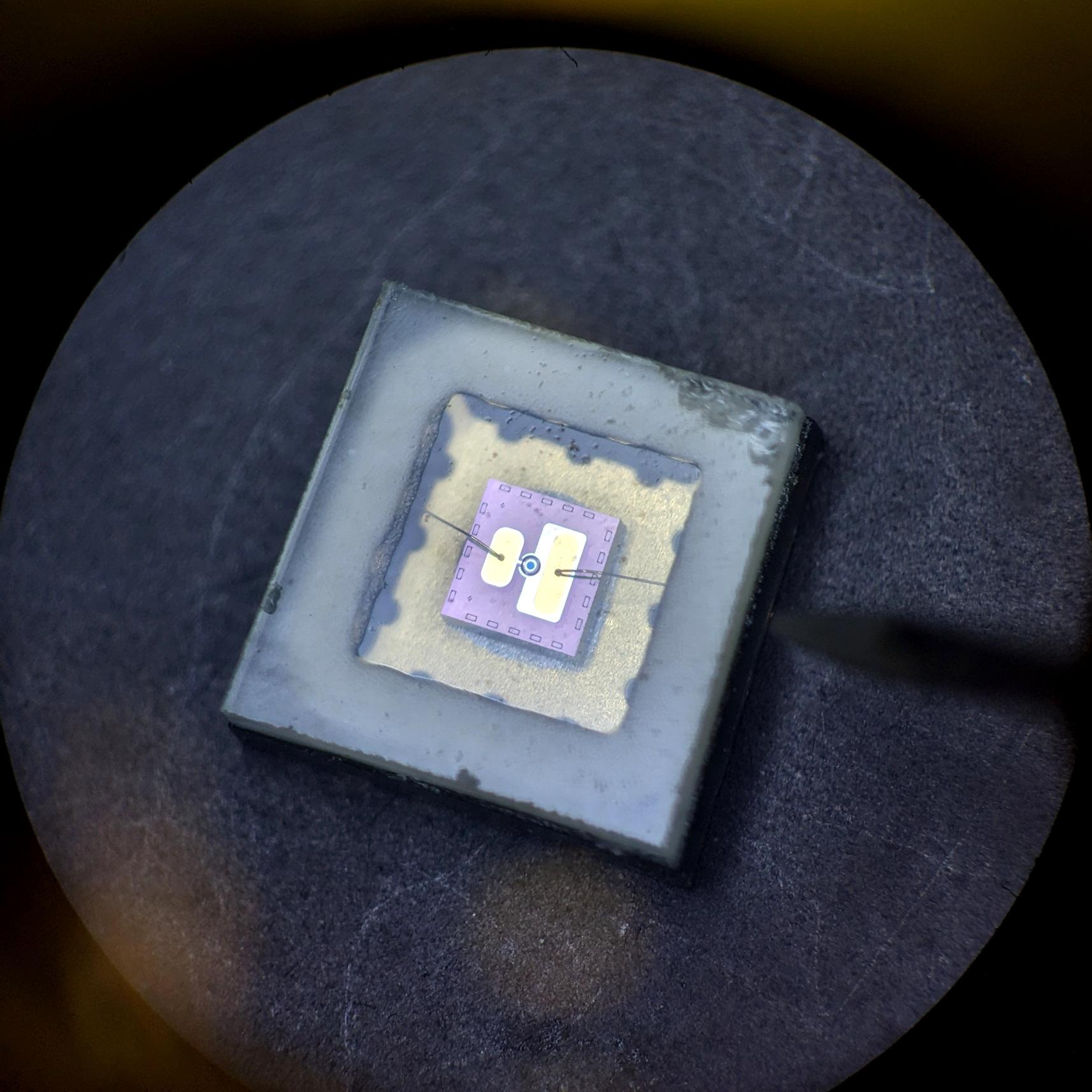

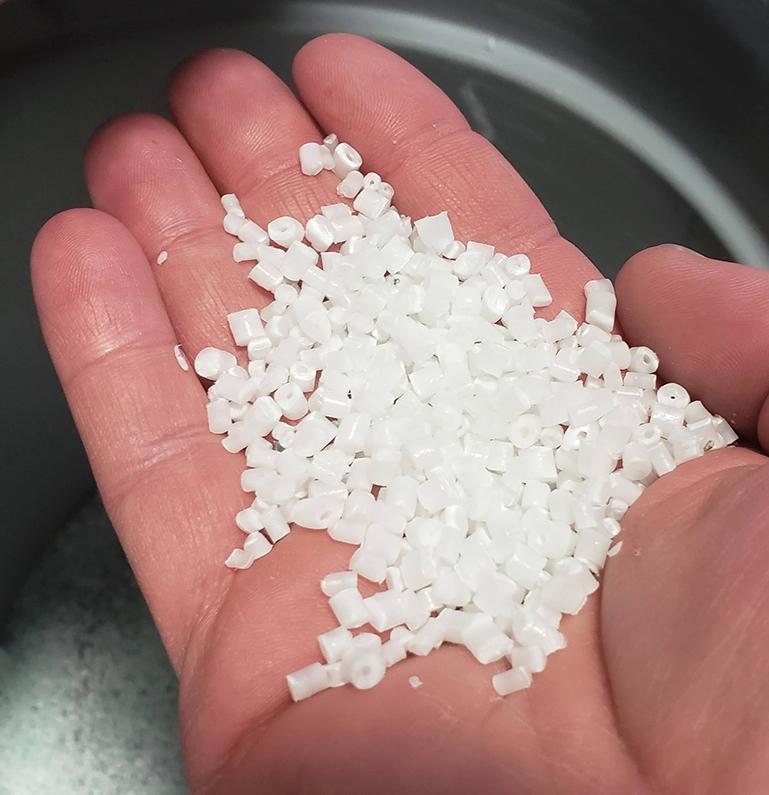

Miller explored advancing high-temperature multi-layer insulation, a method for reflecting radiant heat with metal-coated reflective films separated by thin, non-thermally conductive spacers like felts or polyester netting. It’s a method that works particularly well in the vacuum of space. By the mid-1990s, the space plane project hadn’t made it past the concept stage. But Miller’s developments in the field of multi-layer insulation showed promise, which inspired further work with the space agency. Funded by both NASA and the U.S. Air Force, one of his early improvements was adding small particles called “opacifiers” to felt spacer layers to scatter and block radiant heat.

Another idea he tested was the incorporation of aerogel into felts, first as spacer layers in multilayer insulation and then as standalone insulation. Aerogel is a substance renowned for its heat-insulating properties, a result of it being almost entirely made of air.

“In some cases, insulation is up to 98% porous, so we use aerogels to fill in those gaps,” said Elora Kurz, who manages one of Miller’s current SBIR contracts at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. “And you can use different sizes of aerogels. Steve likes to relate the various sizes of aerogels to filling those gaps with beach balls and ping pong-sized balls to reduce conduction of heat transfer.”

“It’s been this 30- to 40-year collaboration. We would come up with ideas, and then through the smart people at NASA, we could test them,” Miller said. In 2004, he founded a nonprofit research foundation to work on insulating materials for NASA, the military, and others.

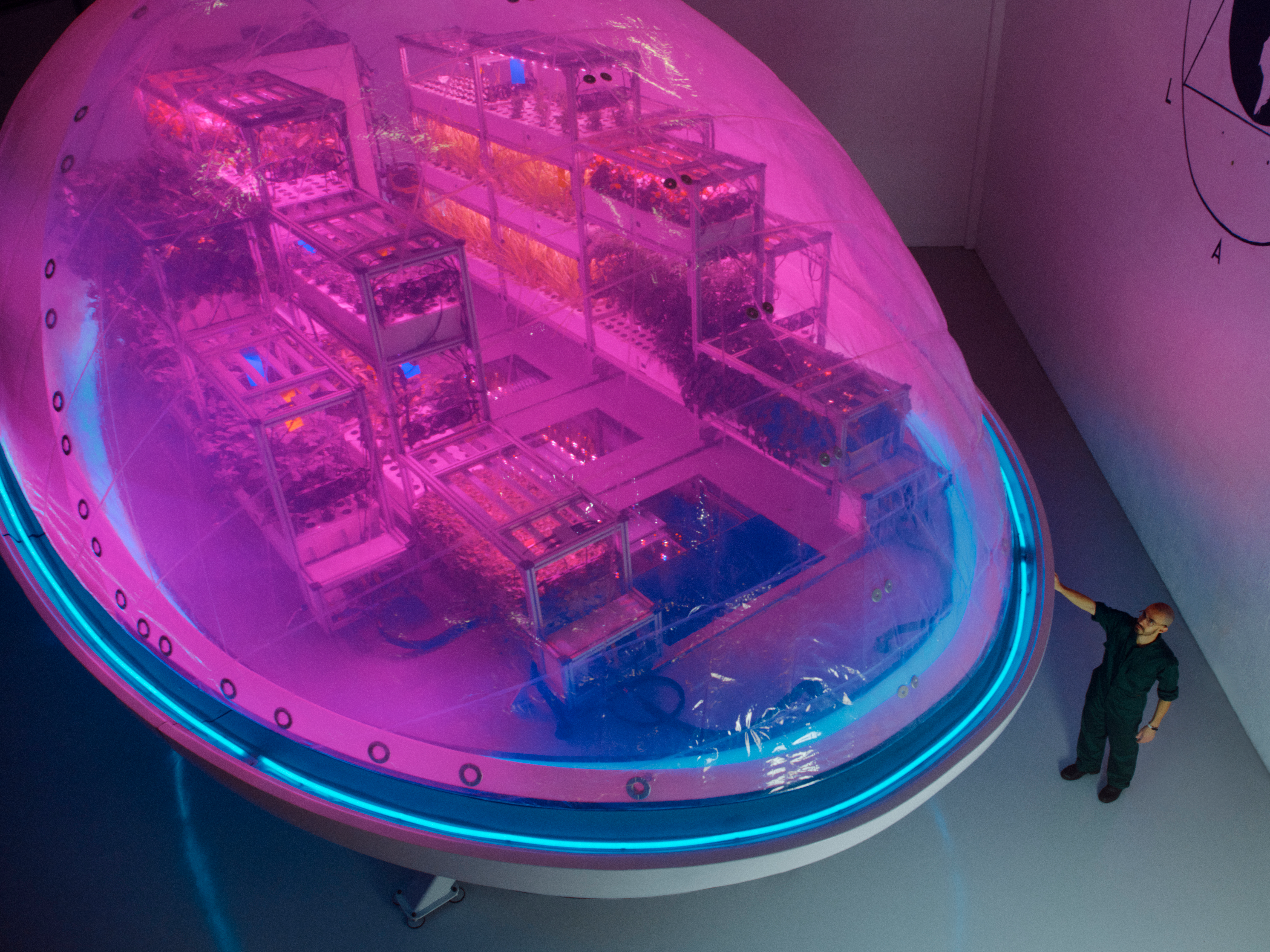

In 2020, Miller’s Flagstaff, Arizona-based company reorganized into Miller Scientific Inc., which operates under the name Heetshield. Shortly after, Heetshield received Phase III SBIR funding to build in-house production capabilities for its aerogel-embedded thermal protection system solutions. Now with the ability to produce this insulation at scale, and further aerogel technology licensed from NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, the company began shopping its thermal protection solutions to the private market. Miller says Heetshield has sold its aerogel thermal protection solutions to small engineering companies and startups like Radian Aerospace, which is looking to build its own fully reusable spaceplane. The company’s latest SBIR contracts, including the one Kurz is managing, have focused on improving the felts needed for the Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerator technology NASA is exploring. In the future, Miller hopes to produce more consumer-focused insulation, such as curtains or window treatments, based on the developments he made with help from NASA.

“I love being the dumbest guy in the room,” Miller said. “When the other people in the room have tested these thermal insulations for their whole careers, you get to pick their brains about how to improve the material or better test it or something like that. That collaboration has given me the opportunity over my entire career to make something useful out of these ideas.”

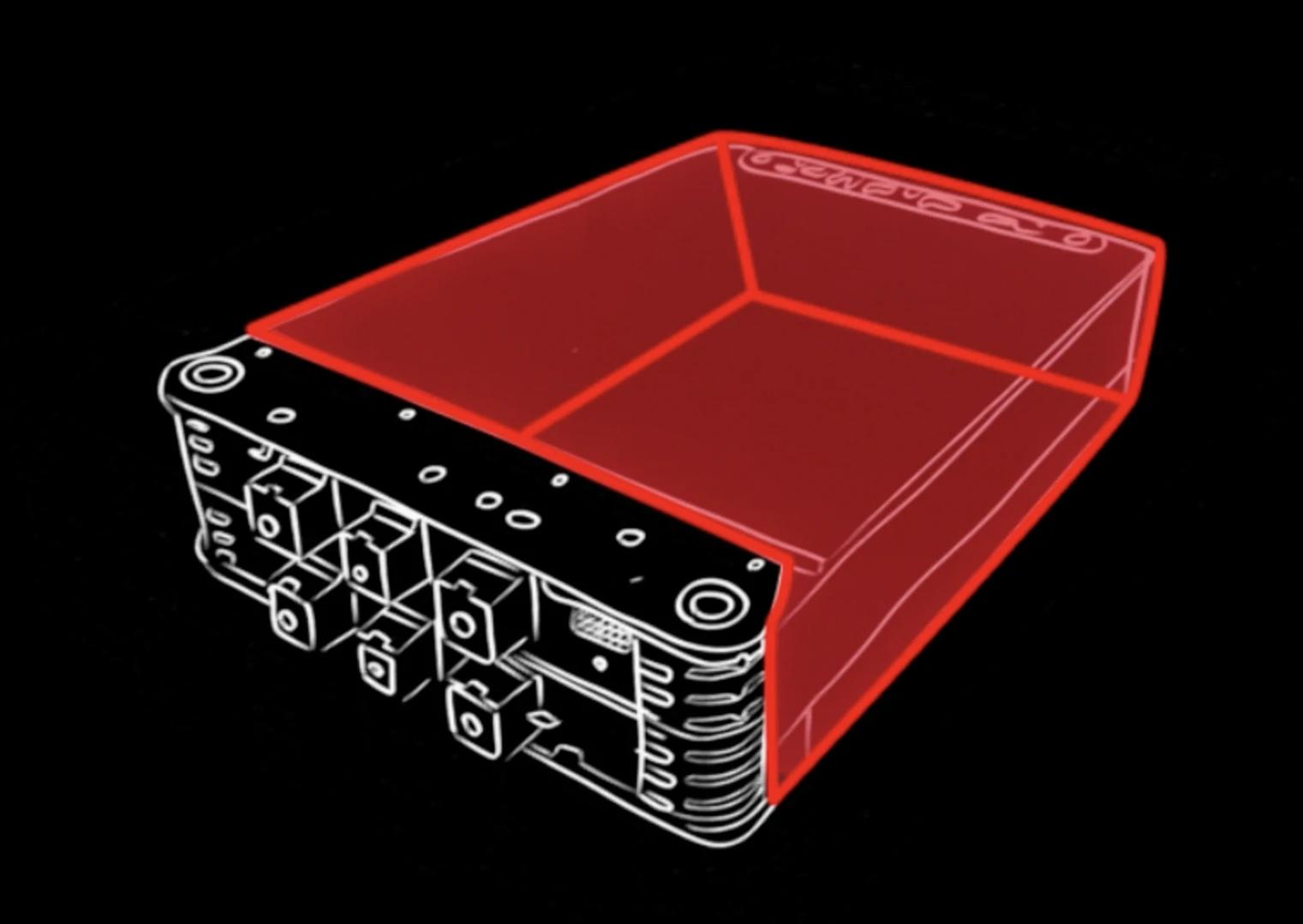

The National Aero-Space Plane (NASP) project was a NASA effort to develop a fully reusable space vehicle. Research into thermal protection systems for the NASP were some of the first Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contracts that Steve Miller had with NASA, which led to the formation of the company Heetshield. Credit: NASA

Assisting NASA’s research into inflatable heat shields for spacecraft is one of the more recent collaborations for Heetshield, which has had several SBIR contracts with Langley Research Center. Credit: NASA