Planet in a Program

Subheadline

Joint effort yields open-source artificial intelligence foundation models of the entire planet

When NASA and IBM released their first version of Prithvi, an open-source artificial intelligence-based model of the planet, in late 2023, they weren’t sure what anyone would do with it. A geospatial model capable of learning about and identifying different aspects of Earth’s surface cover, it had potential for tracking land use or identifying areas of flooding or fire damage.

An application they couldn’t have guessed at was predicting locust breeding grounds in several regions of Africa. But that’s what one group did early on. “They sent an e-mail out of the blue saying, ‘We’ve been trying to solve this problem for a long time, and we were unable to do it until you released this model,’” said Rahul Ramachandran, AI for science lead in the Office of the Chief Science Data Officer at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. “So we were very surprised to see that.”

The team working on Prithvi, which means Earth in Sanskrit, has now published the second version of this geospatial model, as well as another model, Prithvi for Weather and Climate. Both have been downloaded by tens of thousands of users.

Inspired by breakthrough developments in artificial intelligence, the agency teamed up with Armonk, New York-headquartered IBM under a Space Act Agreement to apply the principles of large language models to nonverbal Earth-imaging and weather data, creating living digital models of the globe that could be trained for countless applications.

Bringing Massive Datasets to Life

NASA is constantly developing new ways to make its ever-growing library of Earth-observation data useful to researchers, companies, and laypeople. “There’s a tremendous amount of expense involved in launching these missions and collecting the data,” said Ramachandran. “So part of this office’s mandate is to look at how we can fully utilize this archive of data to further scientific knowledge.”

In the early 2020s, advances in artificial intelligence appeared to provide just such an opening.

IBM and NASA have cooperated on projects since the Apollo days, and when advanced large language models like ChatGPT appeared around the end of 2022, researchers at the two organizations saw an opportunity. IBM was interested “because our main driver is to create the technology that advances the state of the art,” said Juan Bernabé-Moreno, director of IBM Research Europe for Ireland and the United Kingdom and the company’s accelerated discovery lead for climate and sustainability.

First, coders at Marshall and IBM developed a language model called Indus, which is similar to models like ChatGPT but trained exclusively on scientific literature for internal NASA use. Then they wondered about applying a similar method to visual data to create a geospatial model of Earth.

“The approach is a slight modification but the same idea,” said Ramachandran.

Large language models learn by trying to guess which words have been removed from sentences. Instead of using words, the team broke images from Earth-observing satellites down into small patches and hid some of them, he explained. “Now the network has to fill in the patch that’s been hidden.”

In both cases, the algorithms must discover relationships between data points to develop an understanding of the system they’re observing. The eventual result is a foundation model.

A multi-layered neural network trained on vast sets of data, a foundation model can perform many different tasks quickly and accurately, as opposed to the traditional approach of building a model for a specific function. “You have pre-learned so much that you can specialize the model to do many, many things,” Bernabé-Moreno said. “It’s like a true Swiss Army knife. And that was revolutionary.”

Artificial Intelligence, Real Benefits

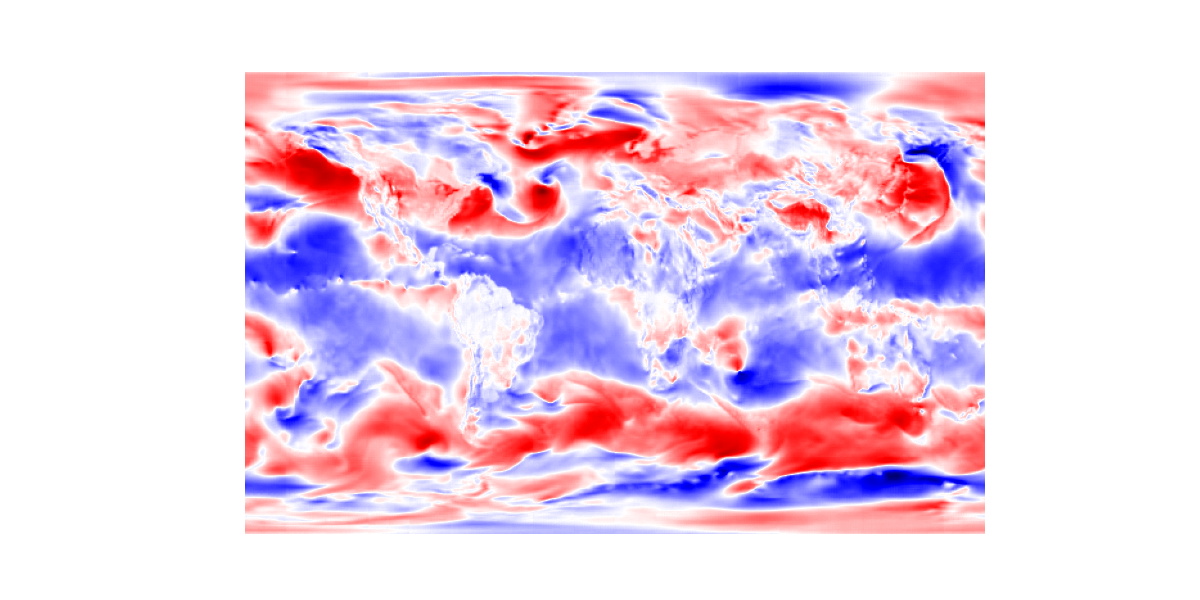

Not only can it be trained for many tasks, but it does them surprisingly well. During the development of the weather and climate model, to demonstrate the system’s power to a skeptical NASA meteorologist, the team removed all but 1% of the pixels from a temperature map of the entire globe. The model was able to accurately recreate the missing 99%.

“And this senior meteorologist said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like that,’” Bernabé-Moreno said. “To be honest, we all were very surprised.”

The second, more comprehensive geospatial model was trained on the last decade of the Harmonized Landsat Sentinel dataset, hosted by NASA, which combines the archives of Landsat and ESA’s (European Space Agency) Sentinel Earth-imaging missions.

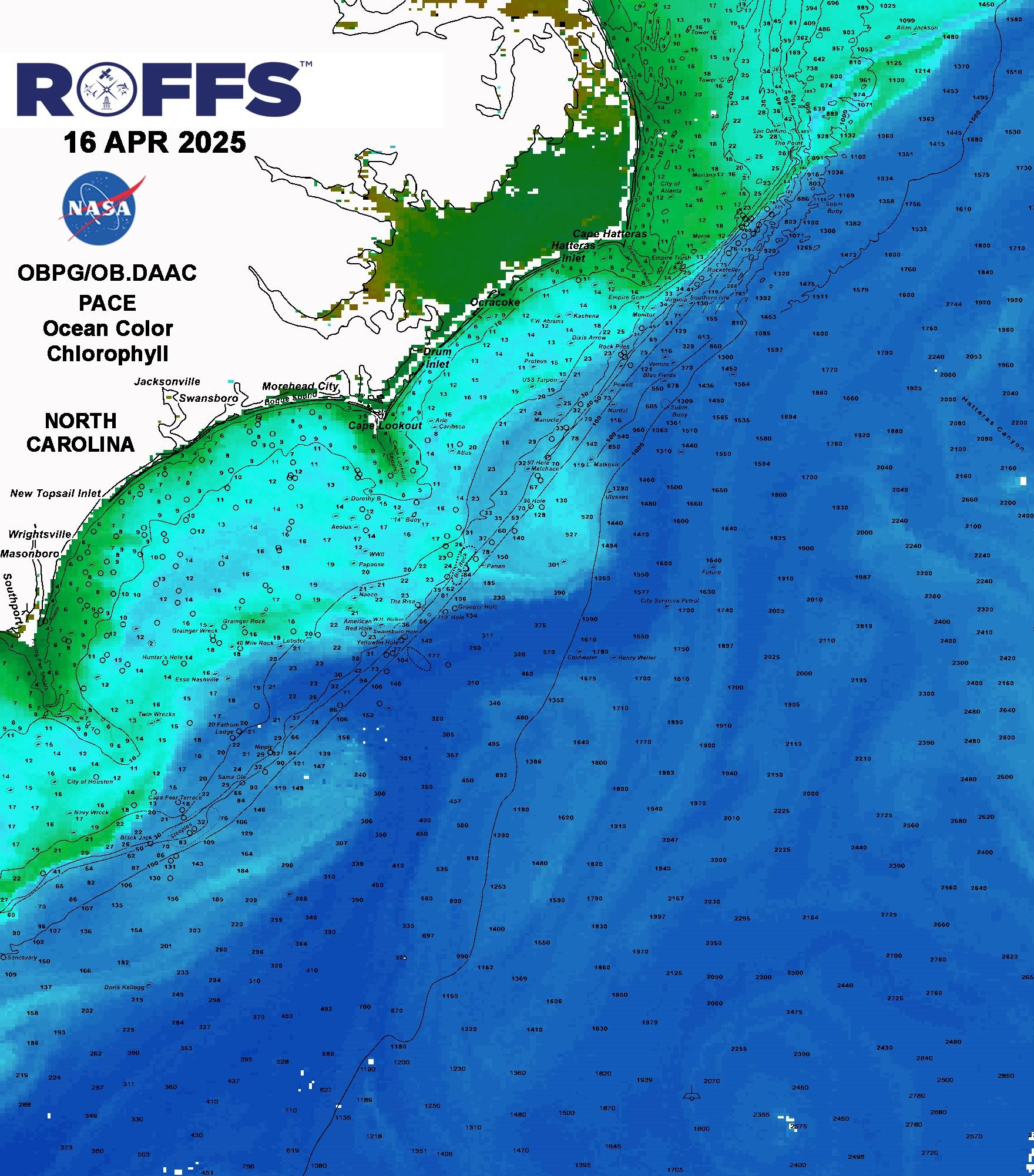

It can tell users about Earth’s surface at the local level or globally. For example, Bernabé-Moreno said, it can be used to detect flooding or the impact of wildfires. Based on as few as 500 examples of flooded or burned land, the system can detect them across the entire planet. It can also classify and identify land cover, for example quantifying worldwide coverage of different crops. And it can assign values to surface areas based on criteria such as their ability to sequester carbon, he said.

In support of reforestation efforts in Kenya, IBM is using the model to quantify forest mass, track forest cover, and identify carbon-capture potential for the carbon credit market. And because Landsat and Sentinel also track surface temperatures, the company was able to detect urban heat islands in Baltimore and Johannesburg.

The weather and climate model, meanwhile, is trained on the Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2) dataset, which is also hosted by NASA and compiles 40 years’ worth of global weather data.

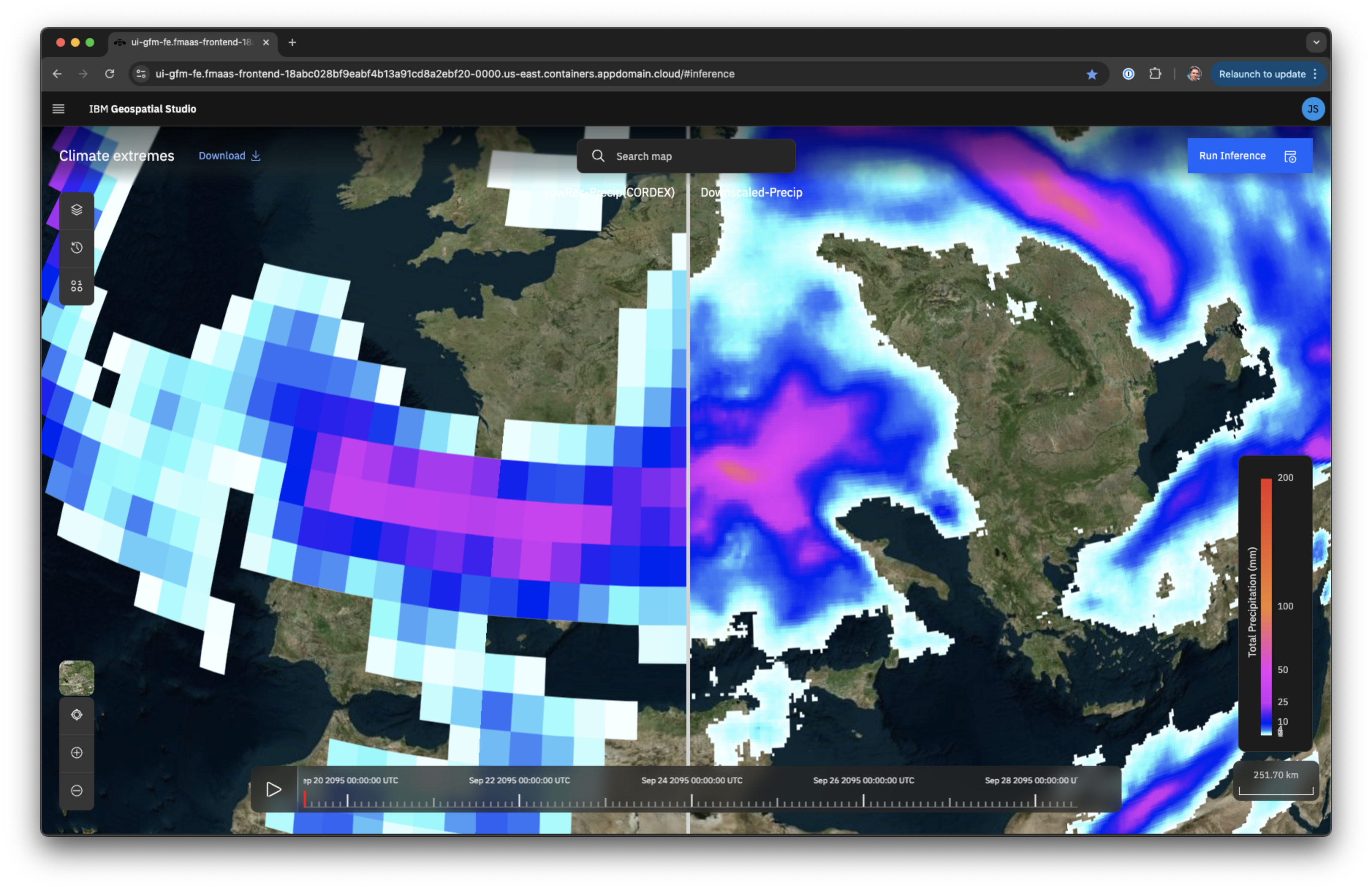

The goal for this model was not just to predict short-term weather — there are plenty of AI models for that already — nor even to predict the climate future. Current models for predicting Earth’s climate decades into the future have very low spatial resolution, and one task the Prithvi weather and climate and model can do well is an operation called downscaling — essentially reducing the pixel size from around 100 miles across to six or seven miles. This shows what averages would be like for a particular area, assuming the climate forecasting model is correct. The team has tested this capability on past data and found it to produce accurate results, Bernabé- Moreno said.

He said the model is also useful for predicting the path of hurricanes, making seasonal forecasts, and combining weather models that have complementary strengths and weaknesses.

Open Development for Widespread Use

The team is already working on the next version of the weather and climate model, and everything is being released publicly on Hugging Face, an open-source machine learning platform.

It’s hard to know who’s using the models for what, but Ramachandran said by May of 2025, the two geospatial models had been downloaded 50,000 to 60,000 times. “So that tells us they’re being used quite extensively.”

Open-source development has been key to rapidly creating models with broad applications, because it allowed the team to gain input and expertise from outside groups, Bernabé-Moreno said.

“We want to build everything transparently — what data went into it, how it was tested,” added Ramachandran. “Our goal is to empower scientists with AI models to accelerate science.”

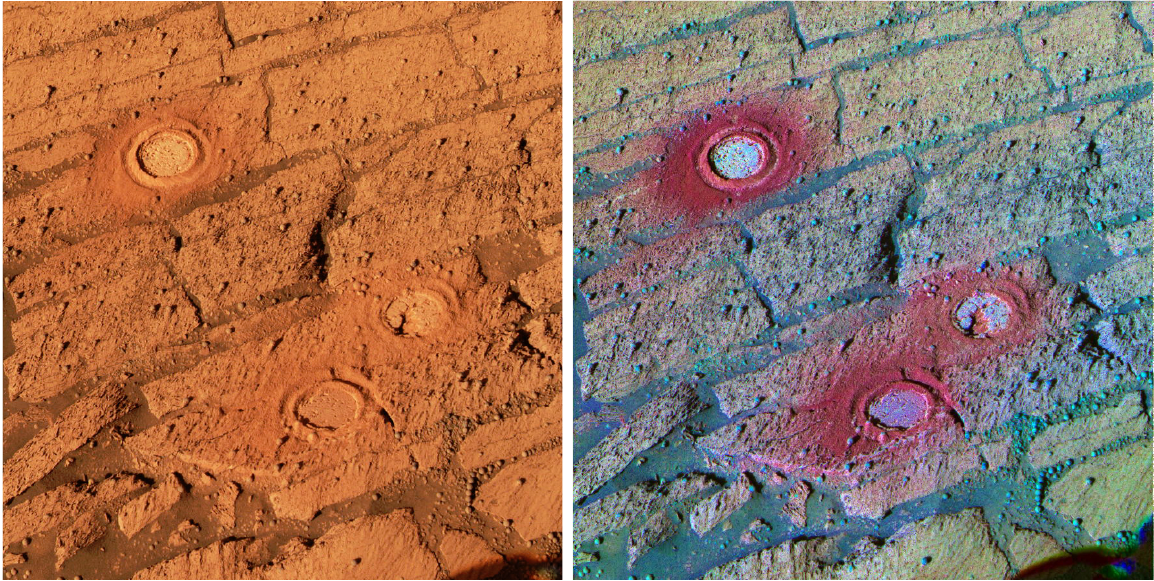

To make AI more widely used throughout the agency, NASA and IBM plan to build a foundation model for each of the five divisions in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, although Earth Sciences has already landed two. A model of the Sun for the Heliophysics Division launched in August of 2025, a Moon model is currently undeway for Planetary Science, and a Mars model is in planning. Models for the divisions of Astrophysics and Biological and Physical Sciences are yet to be planned. A language-based model similar to Indus is in the works for use across the agency, enabling users to more easily interact with all of the NASA-IBM models. This model is intended to accelerate the discovery of insights for the broader scientific community.

IBM, meanwhile, is applying the same idea of foundational AI to the electrical grid, one of the most complex systems ever designed, to prepare it to draw energy from a wider variety of sources, said Bernabé-Moreno. “We really see that these building blocks with NASA can help us massively in our undertaking of creating this great foundation model.”

This example shows how the Prithvi Weather and Climate model can “downscale” climate predictions, which tend to have very low resolution. The downscaled map on the right has 12 times the resolution of the raw data on the left. Credit: IBM Corp.

This six-hour global forecast from the open-source Prithvi Weather and Climate foundation model created by IBM and NASA is an example of a “zero-shot” skill, a skill the model can perform without having been trained on it specifically. Credit: IBM Corp.

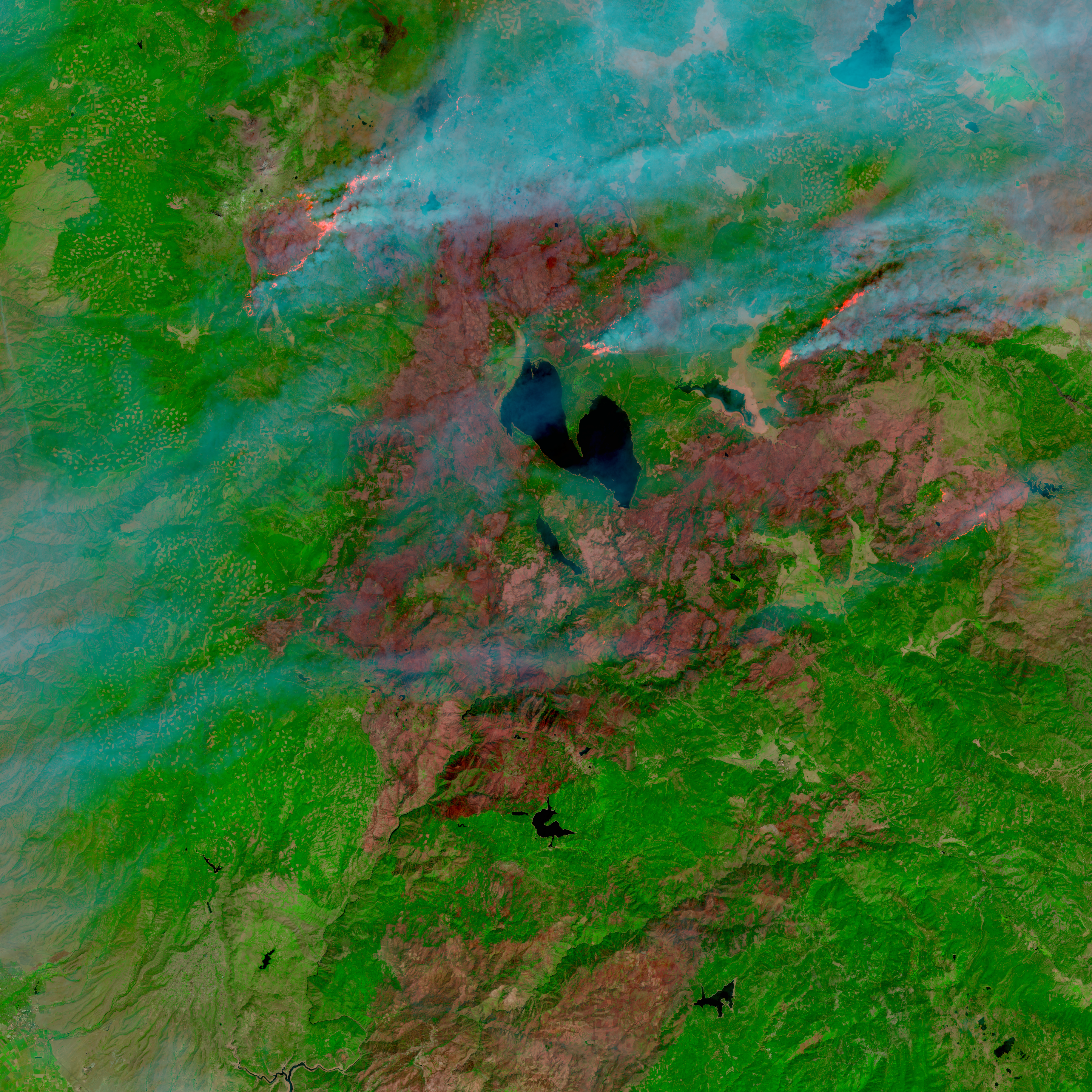

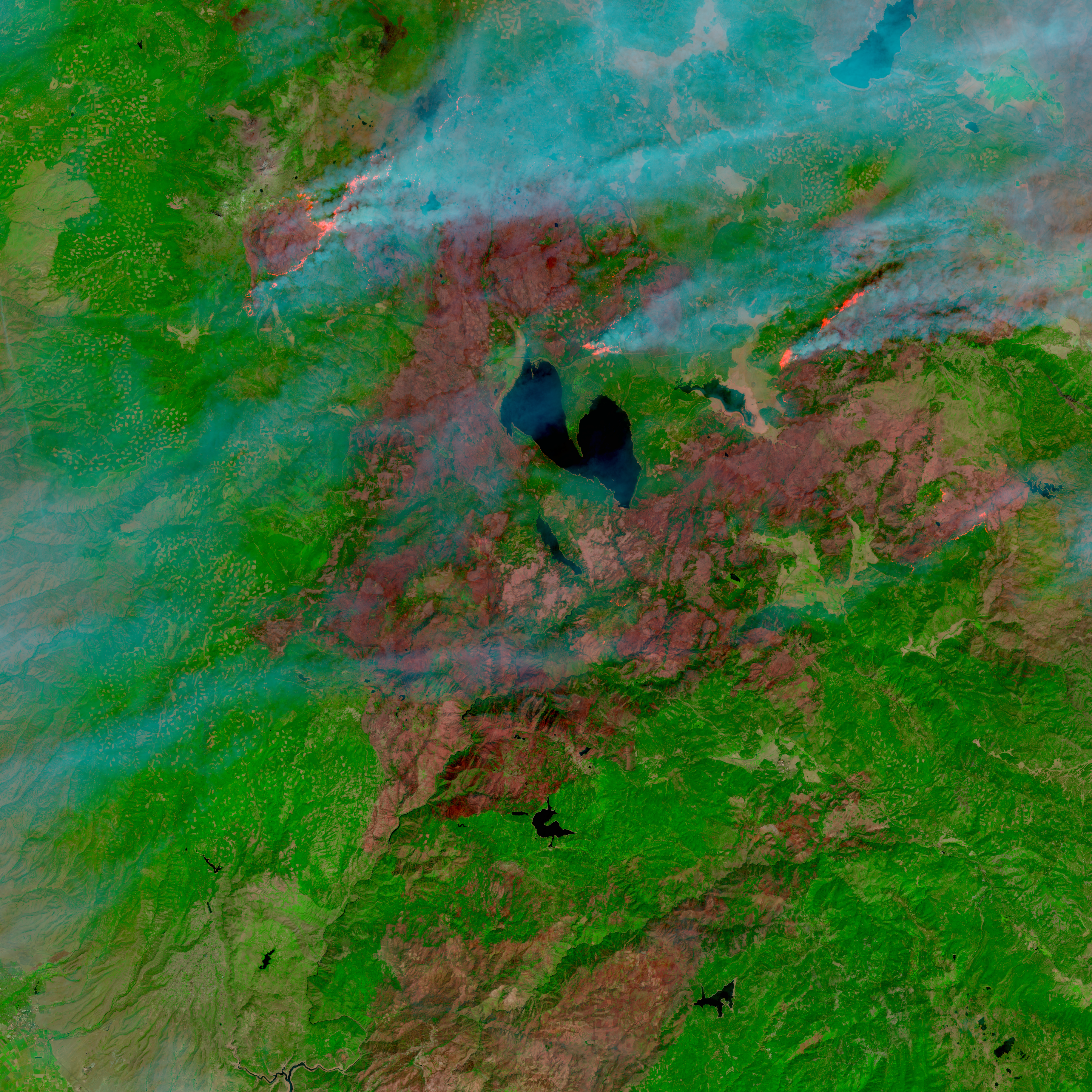

This composite image from the Harmonized Landsat Sentinel (HLS) dataset shows the Dixie fire in Northern California on August 17, 2021, with active fire fronts visible north of Lake Almanor. The open-source Prithvi-EO-2.0 geospatial foundation model created by IBM and NASA was trained on HLS data. One task it’s been trained to do is to spot areas burned by wildfires. Credit: IBM Corp.