NASA Invention Goes Straight to the Heart

Subheadline

Pulmonary artery pressure sensor helps avert heart failure, keep patients out of hospital

It’s a good thing NASA technology is made for long journeys.

A new medical device that’s helping heart failure patients live healthier lives began its daunting trek to market almost 25 years ago at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, when two longtime lab partners observed the clumsy, wired sensors that monitored astronauts’ vital signs while they exercised in space.

“We thought this scheme limits the mobility of the astronauts,” said Rainee Simons. “If you could transmit the data wirelessly from sensors attached to the body to a console, that would be a major benefit to the astronauts.”

By then, he and Félix Miranda had worked together on several communication technologies, including various antennas for space and aeronautics. They knew that a wireless sensor capable of monitoring vital signs, if they could build it, would be useful well beyond space exploration. So they applied for some seed money from Glenn’s Commercial Technology Office — now known as the Office of Technology, Integration and Partnerships — and got to work.

“We are, by training and by experience, always responding to a particular need of the agency but at the same time thinking, what else can we do with this? What kind of needs can be addressed?” said Miranda.

They came up with an all-new radio-frequency device that would enable an unprecedentedly tiny, passive sensor to take measurements and communicate data with no embedded power source.

This little telemetry system, and the handheld device Simons and Miranda designed and demonstrated to get readings from the sensor, led to the development of the implantable Cordella Pulmonary Artery Sensor and Heart Failure System. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for use in heart failure patients in June of 2024.

Rising pressure in the pulmonary artery, which carries blood from the heart to the lungs, is an early indicator of worsening heart failure, often beginning days or weeks before hospitalization becomes necessary, said Harry Rowland. He and heart surgeon Anthony Nunez cofounded Endotronix in 2007 to develop a product inspired by Miranda and Simons’ invention.

“If you can measure that pressure, you can know what’s going wrong early, enabling a clinician to intervene with things as simple as medication changes, which may prevent catastrophic events,” Rowland said. “So this whole idea is all about proactive medical management.”

Following FDA approval, Edwards Lifesciences Corp., a leader in technologies for patients with heart disease, acquired the Naperville, Illinois-based company to bring the Cordella system to more patients around the world.

But arrival at this point was anything but a sure bet.

Double Duty: Channeling Power, Transmitting Data

What Simons and Miranda first patented in 2003 wasn’t itself a sensor but a tiny apparatus that could wirelessly power a little sensor or other microelectromechanical device and transmit information from it. Its secret lay in a multi-turn miniature spiral on a chip only about 1 millimeter square and capable of switching duties between inductor — channeling power from an outside radio-frequency ping and using it to get a sensor reading — and antenna, to send back a signal.

Though the invention was conceived for sensors on the skin, when the two engineers talked to potential users, they discovered the medical community was more interested in it for implantable devices. With a tiny profile, no wires, and no batteries, it was an ideal medical implant.

“There was a lot of interest from the medical community, for bone density measurements, for spinal cord injury patients, for monitoring the healing process,” said Simons. So they tested it to prove it could receive and send signals through simulated body tissue.

Meanwhile, they developed a handheld device that could remotely couple with the little implant to momentarily power a sensor and then receive a reading from it. To keep the implant as small as possible, they put all the burden of signal amplification on the handheld reader.

After the reader was patented in 2007, they published papers describing their invention. One of those caught Nunez’s attention.

A heart surgeon in Peoria, Illinois, Nunez had recently been introduced to the concept of wireless pressure-sensing implants and was exploring the idea for various applications. This interest had led to his introduction to Rowland, who had just completed his Ph.D. in micromechanical engineering and nanotechnology manufacturing and was meeting with physicians around Illinois to discuss potential healthcare applications.

They began working together and went to meet Miranda and Simons to learn about their technology. Shortly after, they founded Endotronix, and the team began work under a Space Act Agreement to exclusively license the NASA technology for cardiovascular applications.

Measuring Where It Matters

They first set about bringing it up to the standards for a commercial medical device. “As we went to address the problem of heart failure management, we brought other technologies into play to make the solution actionable and practical in the real world,” said Rowland, now senior vice president of implantable heart failure management innovation at Edwards.

They ended up with more than 30 patents, covering everything from the core technology to apps for the patient and physician to access the health data. “You needed many types of expertise to help bring this technology to life,” said Rowland.

They settled on the pulmonary artery for early detection of heart failure, as heart failure hospitalizations occur when pressure builds until fluid seeps into the lungs. Any heart failure patients regularly measure their blood pressure, but pressure in the arm doesn’t necessarily reflect what’s going on around the heart, Rowland said. “You have to measure it where it matters to be able to manage heart failure effectively.”

Beginning in 2017, the device underwent multiple clinical trials, ultimately treating more than 600 people. One trial showed a 73% reduction in heart failure hospitalizations at one year after the devices were implanted.

While the early warning of rising pulmonary artery pressure is key to prevention, Rowland said, the system also provides patients with easy, real-time access to accurate information about their heart health. This helps them see the impact of their lifestyle, helping them make healthier choices.

Less than a year after Cordella’s FDA approval, Endotronix, now the Implantable Heart Failure Management unit of Edwards, is commercially launching the Cordella system and has nearly doubled to over 250 employees.

And more than two decades after their first patent on the technology, Simons and Miranda said their work is finally paying off. “This is where the real reward comes, to see that the technology is helping a lot of people,” Miranda said.

But their invention has also spurred advances in other fields. Simons noted that more than 60 patents cite their original patents as prior art and apply the technology to monitoring anything from other aspects of human health to bridges and buildings. “We were the pioneers in demonstrating that a printed spiral on a chip can have dual function, both as an inductor as well as an antenna,” he said.

As for monitoring astronauts’ vital signs in space? “The farther they go from Earth, the higher the likelihood they will need medical attention,” Miranda said. “This could be a tool in their toolbox.”

Two NASA engineers had the idea that allowed the Cordella Pulmonary Artery Sensor to be tiny enough to implant in the pulmonary artery. The sensor has malleable anchors that conform to the artery walls to ensure stable positioning. Credit: Edwards Lifesciences Corp.

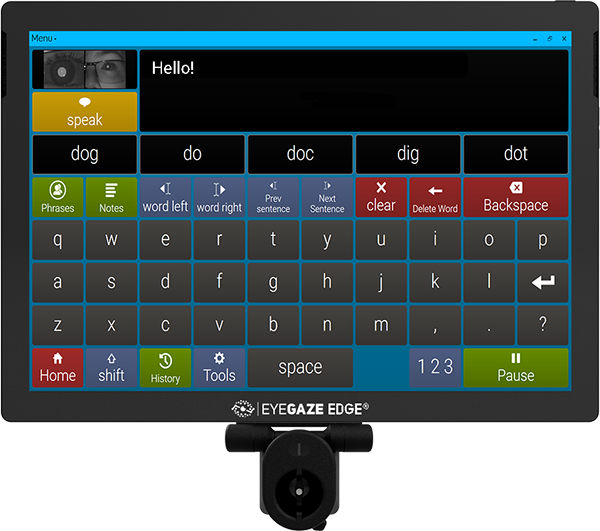

This handheld reader pings the implanted Cordella sensor with a radio frequency and receives a response that indicates the pressure in the pulmonary artery. Credit: Edwards Lifesciences Corp.

A patient using the implantable Cordella Pulmonary Artery Sensor and Heart Failure System holds the reader to the chest and then gets the results through an app. Credit: Edwards Lifesciences Corp.

The Cordella sensor is shown strung onto the delivery device that’s used to implant it in the pulmonary artery. Credit: Edwards Lifesciences Corp.

Astronaut Michael Lopez-Alegria carries out a pre-breathe exercise in preparation for a spacewalk. Astronauts’ vital signs are closely monitored during pre-breathing, as they exercise while breathing pure oxygen to avoid decompression sickness. Two Glenn Research Center engineers thought wireless sensors would be less cumbersome, so they invented the system that eventually led to the Cordella Pulmonary Artery Sensor and Heart Failure System. Credit: NASA