Teaching an Old Metal New Tricks

Subheadline

NASA data enables industry’s continued use of shape-changing memory alloy

A memory alloy invented more than 60 years ago isn’t gracefully sliding into old age — it’s just getting started. With new formulations and manufacturing techniques, nitinol is proving its staying power. An alloy of nickel and titanium, nitinol’s name takes letters from the two metals and the Naval Ordnance Laboratory that discovered its properties in 1959. Decades of innovation by the space agency and commercial companies have resulted in new formulations and manufacturing processes that are finding new uses on Earth and in space.

Extensive testing of the alloy sponsored by NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, in the late 1960s generated a wealth of data. The center’s Technology Utilization Office, recognizing the commercial potential, published a paper about it in 1972. That paper became the basis for the nitinol products developed by Metalwerks Inc., located in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania.

NASA continues to work with the alloy to improve applications in the aeronautics and automotive industries.

“These materials have the ability to convert heat into motion,” said Othmane Benafan, a materials research engineer at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. It exhibits “shape memory.” After a part is manufactured in a specific shape, it will change or deform into another shape when heat is applied. That same part will return to the original form when cooled. This superelastic property means the part can also be twisted or extended.

Because nitinol functions in both hot and cold environments, it’s particularly beneficial in space, where temperature swings are extreme. “One space application is using nitinol as part of a thermal system. It can absorb heat to support cooling and then eject that same heat when warming is needed,” said Benafan. “It can be used to cool habitats or to maintain a fuel tank temperature and doesn’t require a motor to accomplish either.” It’s also strong and corrosion-resistant.

All of these characteristics make it a valuable resource on Earth. Nitinol is used in dentistry as orthodontic wires (Spinoff 1979) and in medicine for heart valves and stents. Metalwerks produces medical-grade nitinol for a number of customers, and its nitinol formulations started with the published NASA data.

“The industry is still developing applications for nitinol 66 years later as a result of research in the space program,” said George Kramer, president of Metalwerks. In addition to manufacturing nitinol, the company established an induction melting process that produces the alloy “in its cleanest form,” according to Benafan.

Because the substance is difficult to manufacture, and therefore expensive, aerospace companies were the only customers for a while. But Metalwerks now supports customers in commercial space and has expanded its reach in the medical and dental-device manufacturing industry, said Kramer. In addition to supplying NASA with batches of nitinol using new formulas for its ongoing research, the company supports high-tech manufacturing customers.

In one example of NASA’s continued work with the alloy, in the 2000s, the agency worked with Abbott Ball to develop a manufacturing process for corrosion-resistant ball bearings (Spinoff 2015).

As NASA continues to research nitinol’s capabilities, new applications will benefit from the durability, light weight, flexibility, and shape-changing characteristics of the alloy, said Benafan. Some of those include automotive, commercial aviation, air conditioning, and mining.

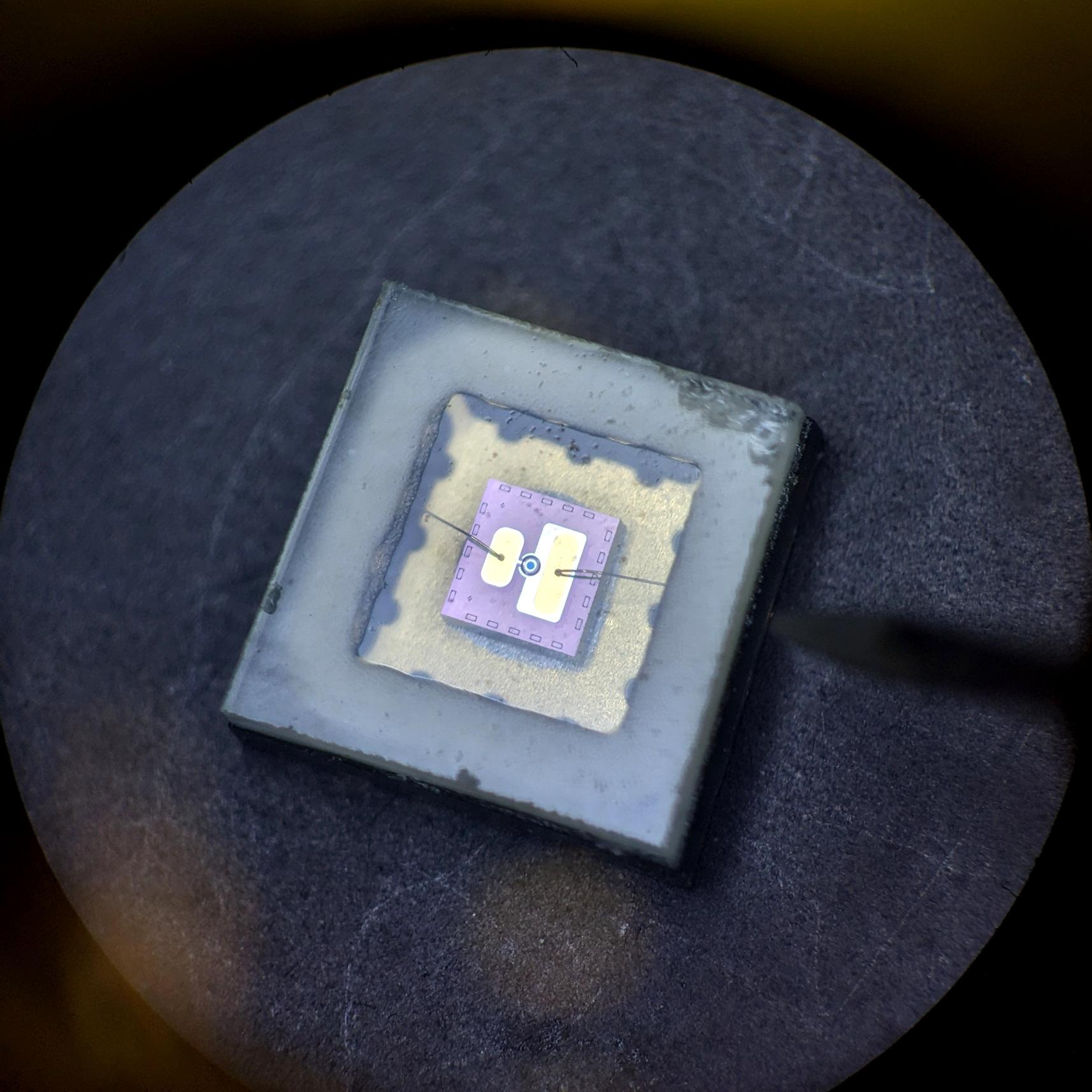

After it deforms, a part made of the alloy nitinol will return to its original shape under a set temperature. This twisted paperclip made of nitinol wire demonstrates how warm water activates the metal memory. Credit: Petermaerki CC BY-SA 3.0