Spotting Invisible Gas Leaks

Subheadline

Processed satellite imagery helps companies identify and contain methane losses

About 3% of the natural gas that’s captured by producers is lost through leaks before it can be used, according to Momentick Ltd. of Tel Aviv, Israel. That represents an industry-wide loss of about $60 billion per year. Now that company is using satellite imagery to spot those methane plumes and help companies stem their losses.

Momentick relies on several different Earth-imaging satellites, especially the joint NASA-U.S. Geological Survey Landsat satellites, as well as ESA’s (European Space Agency) Sentinel constellation, because both programs’ imagery is frequently updated and free of charge. Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, oversees NASA's portion of the Landsat program.

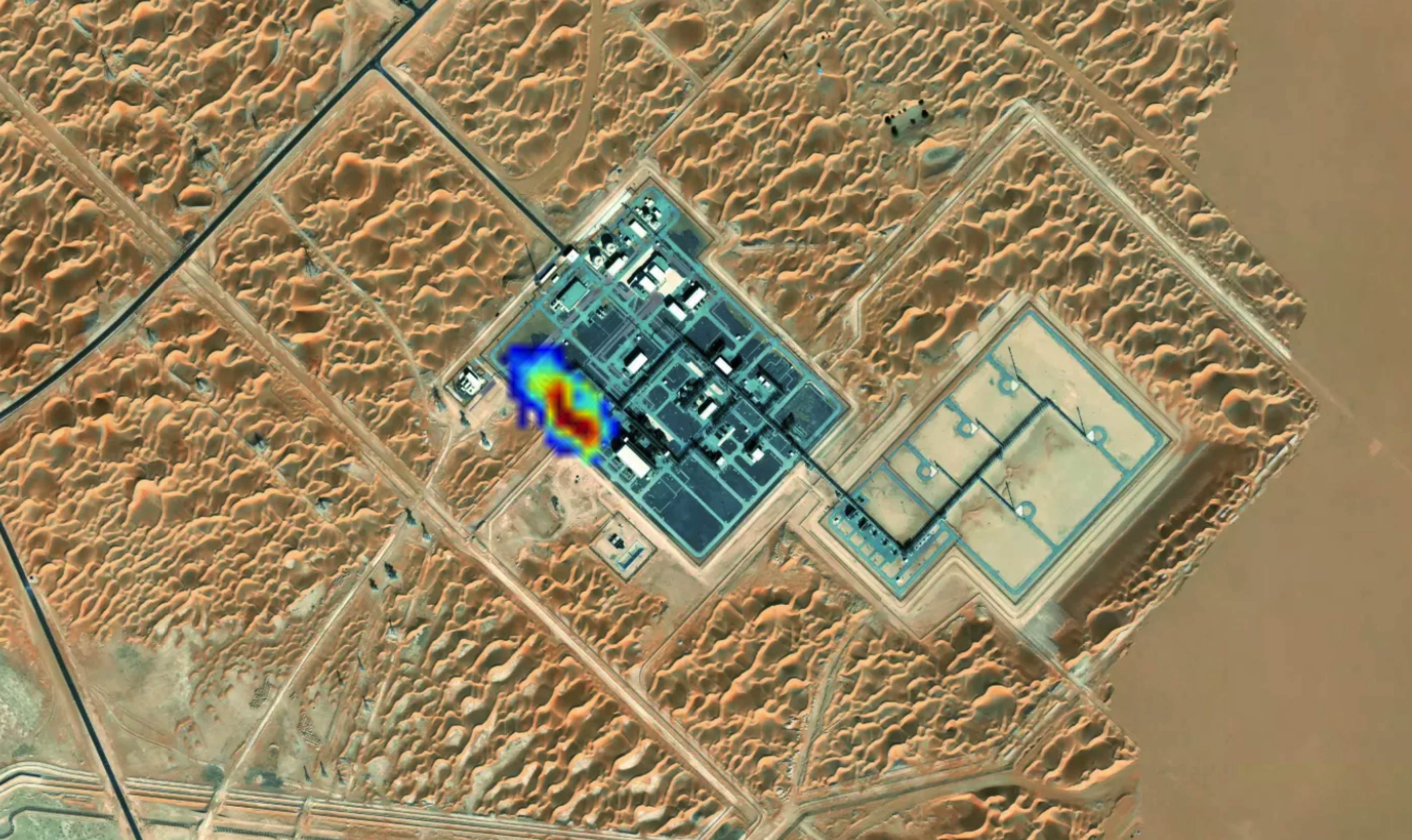

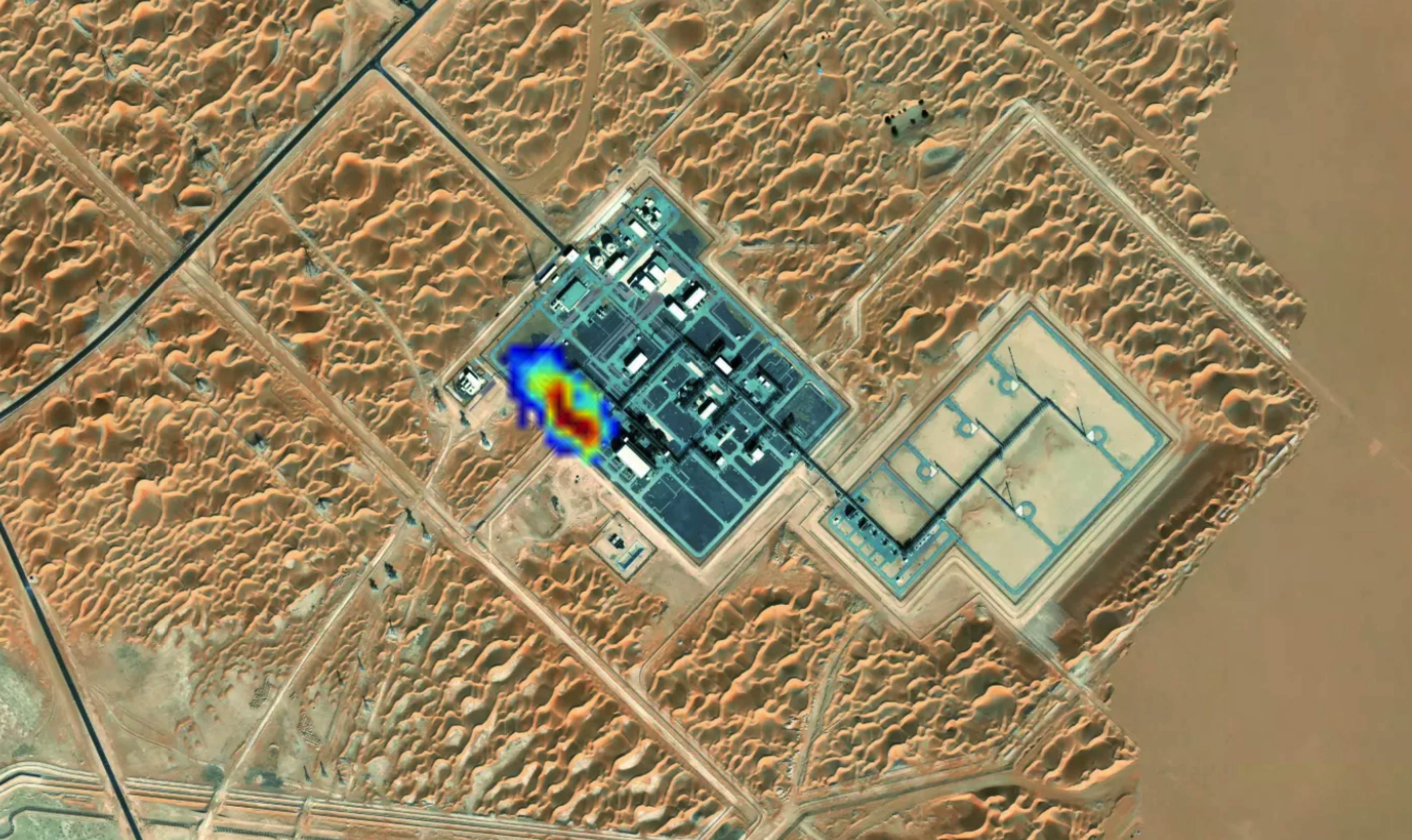

Methane, the main component of natural gas, is not visible to the naked eye. The company uses proprietary image-processing algorithms that utilize the short-wave infrared wavelengths, which are affected by methane, along with other wavelengths that are not. It takes a few hours of processing to reveal the methane signature, which shows not only the presence of the gas but also its concentration and emission rate, CEO and cofounder Daniel Kashmir explained.

The technique can accurately measure plumes as slow as about 2,400 pounds per hour, but Momentick’s system is tailored to detect the presence of plumes below that level and report them along with a level of confidence. A plume of that size might be normal for a gas field or oil pad — oil drilling often releases natural gases — but these are dwarfed by the sort of leaks that can pour out of offshore rigs, said Omer Shenhar, the company’s vice president of product.

This is where the Landsat satellites present a particular advantage. Though offshore rigs might emit plumes of hundreds of thousands of pounds per hour, they’re difficult to detect. Readings rely on reflected light, and deep water absorbs most of the Sun’s light. While the Sentinel constellation has better spatial resolution than Landsat, the latter has its advantages when it comes to light exposure and bandwidths, explained Dr. Adam Eshel, Momentick’s chief technology officer.

The company’s services should pay for themselves by eliminating product losses, said company spokesperson Mira Marcus. She noted that they also help companies avoid fines as regulations on emissions become stricter around the world. For example, the European Union is now putting emissions limits on oil and gas importers. Because the biggest players by now have their own methane trackers, it’s the small and mid-size companies that are turning to Momentick, Marcus said. And pipeline operators especially stand to benefit, she added, as it’s difficult and expensive to monitor hundreds of miles of pipeline manually or with drones.

Other customers include insurers that serve the oil and gas industry and need to assess their risks, as well as governments looking to enforce regulations and base policies on current data, she said. In the future, the company plans to serve the waste management industry, measuring emissions from landfills and dumpsites. Agriculture is another possible market.

Momentick employs about 20 people. Landsat has been important to the company’s business model, Marcus said. “Thanks to using Landsat and it being free, we’re able to lower our pricing to make it more appealing and cost-effective to companies.”

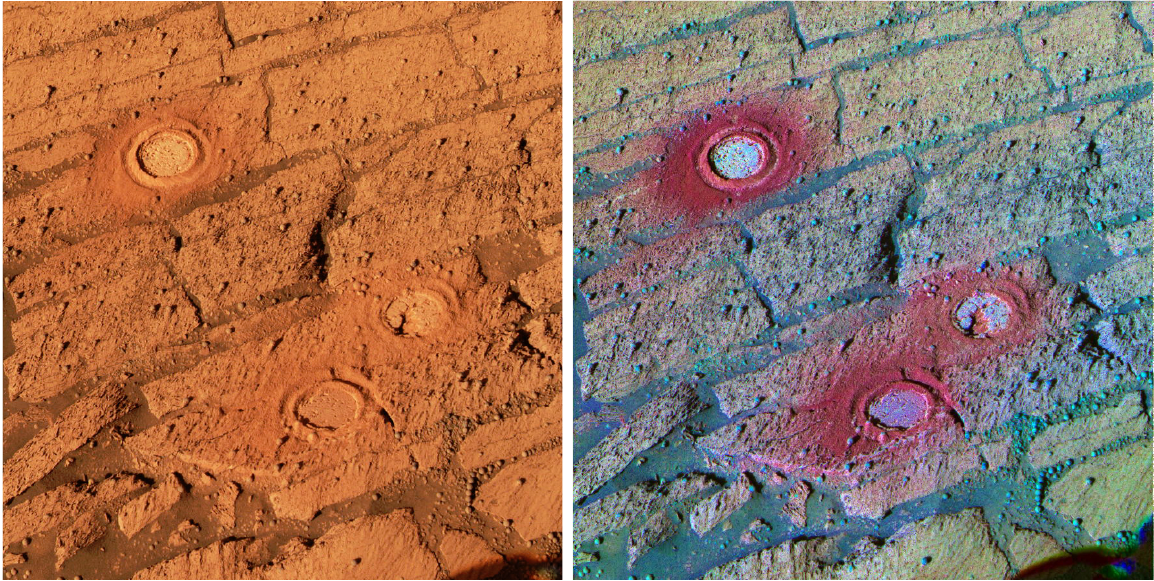

Offshore oil and gas operations are often among the biggest emitters of methane, yet their plumes are the hardest to spot. This is because techniques for identifying escaped methane rely on reflected sunlight, and oceans absorb most light. Landsat, however, offers certain advantages in light exposure and bandwidths. Credit: Getty Images

In this satellite image of an oil field in the United Arab Emirates, Momentick’s technology was able to detect a methane plume of more than 4,250 pounds per hour. Credit: Momentick Ltd.