Technique for Manipulating Satellite Photos Now Reveals Ancient Images

Subheadline

Algorithm NASA first applied to satellite imagery is now used to peer into antiquity

On the walls of a chamber near the top of the central tower in the ancient Cambodian temple Angkor Wat, paintings depict horseback riders and a traditional musical ensemble. Every day, thousands of visitors pass these images without noticing, because they’re faded to the point of invisibility.

They were discovered, along with about 200 other paintings throughout the sprawling complex, between 2010 and 2012 by a Singaporean archaeologist using a method conceived at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

The technique, known as decorrelation stretch, heightens contrasts in digital imagery, making subtle differences clearer and features easier to spot. Originally used by NASA to extract more information from satellite imagery, it has proven useful in many fields but has come to be especially widely used for studying ancient rock art. This is partly because these images are commonly faded beyond recognition. But it’s also due to the chance intersection of one man’s hobby with his unrelated professional and educational background.

In the 1980s, one of Jon Harman’s friends brought him along on a few field trips with a local rock art group, and the mystery surrounding these ancient images intrigued him. “No one really knows why people made the rock art they made, at least in many cases,” he said. “And the symbols are quite strange.”

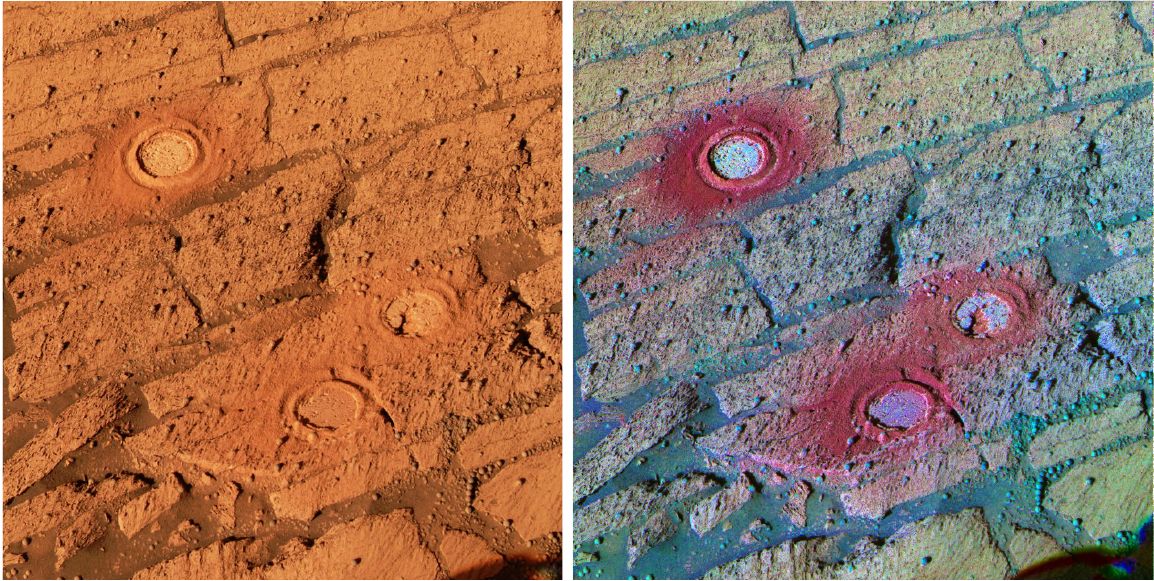

At a rock art conference around 2005, someone showed him images from NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover webpage, depicting the Martian surface with and without the application of decorrelation stretch. Seeing how much detail the technique revealed, he understood the implication for studying ancient, faded images.

He also happened to work in medical imaging. “I Googled it and found a NASA paper that explained how to do the algorithm,” he said. “I knew from my medical imaging experience that I could do it, so I did.”

Thus was born the Dstretch plug-in and, later, Dstretch apps for Android and iOS.

Rather than simply raising the contrast between colors, decorrelation stretch maps the original colors to a different, expanded range of colors. It’s a complicated process that includes steps like diagonalizing color matrices. “Diagonalizing is algebra, and I have a PhD in math from Berkeley, where I studied algebra,” said Harman, now retired in Pacifica, California.

The technique is based on the Karhunen–Loève Transform, a theorem used in statistical analysis and coinvented by Michel Loève, one of Harman’s former math professors.

The Dstretch plug-in is for use with ImageJ, an open-source image processing and analysis program originally developed by the National Institutes of Health.

From Statistics to Geology

The paper Harman found detailing the process was written in 1996 by Ronald Alley, a JPL employee who at the time was part of an international team developing scientific requirements for the upcoming Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER). That imager, built by Japan, was launched in 1999 on the Terra satellite, where it still operates today alongside its more famous counterpart, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, or MODIS.

In the 1990s, Alley was working with a group of geologists at JPL, finding applications for satellite data. But he had previously worked in a digital image-processing group, and his supervisor there, Jim Soha, had cowritten a 1978 paper along with another JPL employee that proposed applying the Karhunen–Loève Transform to digital imagery for color enhancement. It was this technique that came to be called decorrelation stretch, and Soha’s group is where Alley learned to use it.

By the time scientists were making plans for ASTER, Alley and his geologist colleagues had been using decorrelation stretch to map lava flows on the big island of Hawaii for some time.

The original technique involved creating multiple intermediate images, each of which introduced slight inaccuracies through rounding. By replacing that process with one called matrix multiplication, Alley made decorrelation stretch both faster and more accurate.

He knew it would be useful for a multispectral imager like ASTER, which collects data in the visible spectrum and different infrared ranges, so he wrote the paper. “Someone had to write up a description of this thing so users would know what we were talking about,” he said.

Michael Abrams, the current ASTER science team leader, said his group still uses decorrelation stretch on infrared imagery to track plumes from volcanic eruptions, whose sulfur dioxide, ash, and water vapor have distinct infrared absorption bands.

Dstretch User Base Expands

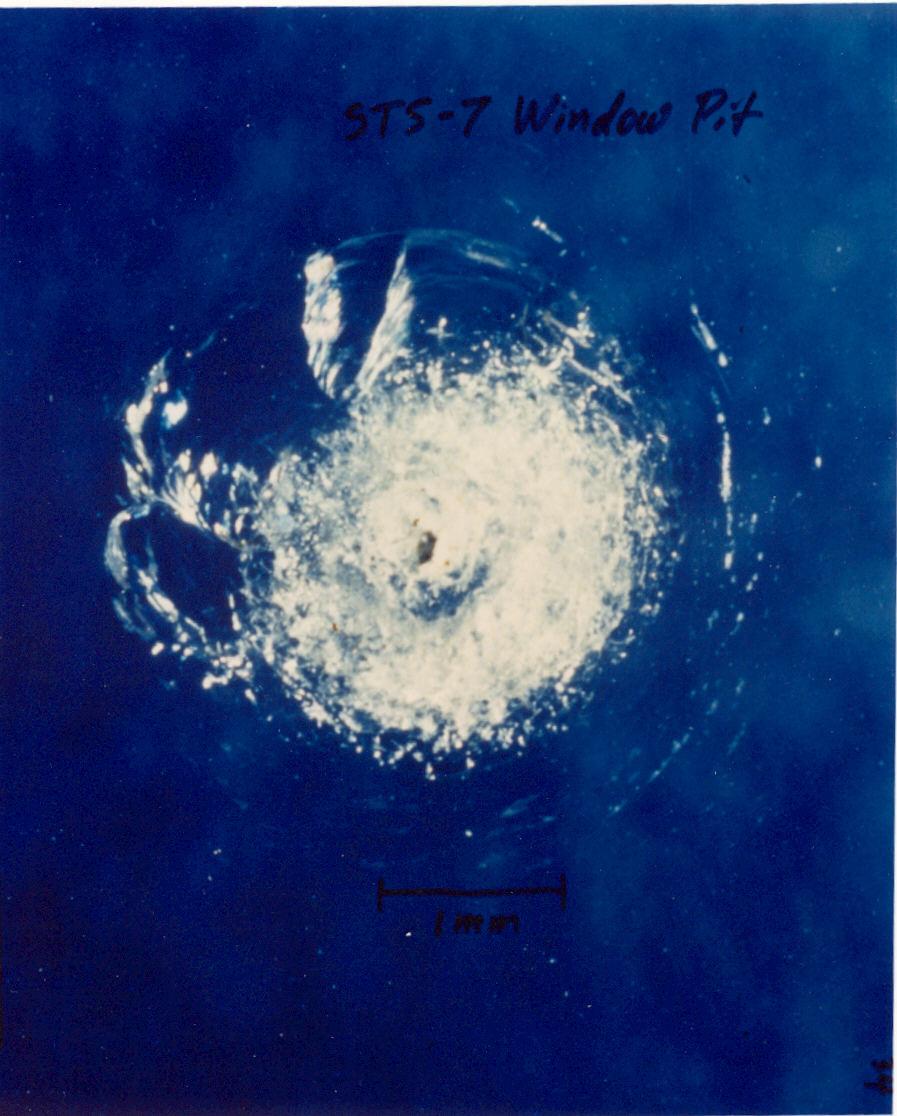

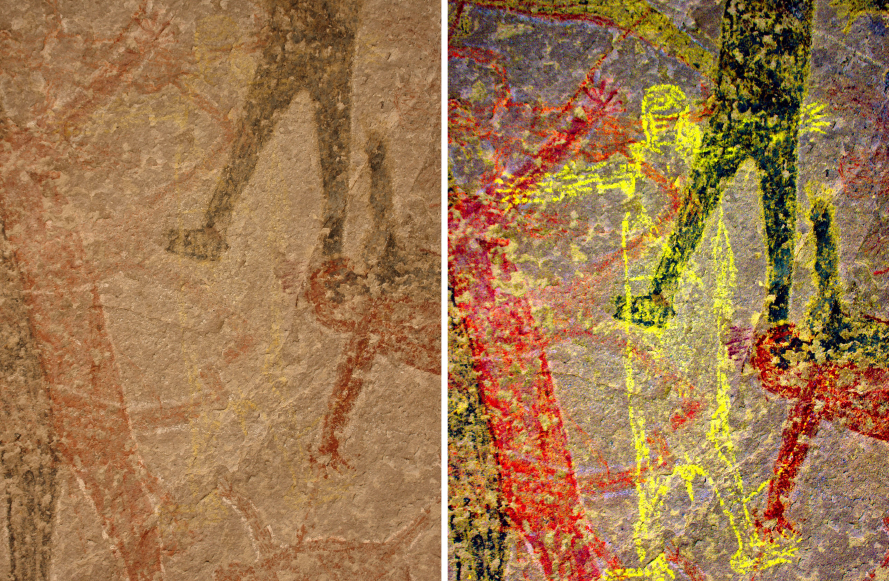

Harman first applied his Dstretch plug-in to photos he had taken of rock art in Baja California, Mexico. In one image featuring several human figures, a new yellow figure seemed to materialize from nowhere when the algorithm was applied. “That convinced me of the usefulness,” he said. “Then I started playing around and found that by changing the color space I was working in, I could get good results in different images.”

A color space is a range of numerically represented colors, such as the red-green-blue, or RGB, color space common among screen devices. Dstretch includes custom color spaces that have proven useful with Harman’s extensive image collection. In this way, Dstretch is tailored to rock art, but it can be and is used in many other contexts.

Harman said he gets about 200 requests per year from all over the world, which he fulfills for $50 apiece. Around 2010, he created smartphone apps that use a shortcut to mimic decorrelation stretch. “To do the actual Dstretch on a phone would be difficult and take forever,” he said. The apps cost $20 and have been downloaded thousands of times. Papers have been published describing Dstretch’s usefulness in archaeology.

Space Technology Down to Earth, Then Underground

Pictographs at the Årsand 1 site in western Norway, including a sun, stylized human figures, and various shapes and patterns, were first documented in 1940. The use of Dstretch in 2008 and 2012 uncovered about 15 previously undocumented figures and revealed new details in 28 others.

In the ancient Egyptian cemetery of Beni Hassan, archaeologists used Dstretch to discover images of bats and pigs, animals rarely depicted in ancient Egyptian art.

In Alberta, Canada’s Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, famous for its indigenous rock carvings and paintings, Dstretch revealed what could be considered an early form of graffiti “tagging.” A pictograph of a horse and rider is believed to serve as a “calling card” from a Crow warrior, taunting his Blackfoot enemies.

But the plug-in has also found use beyond rock art. The site of Vlochos in Thessaly, Greece, contains the remains of urban settlements built between 500 B.C.E. and 800 C.E. There, Dstretch applied to aerial imagery revealed areas of potential archaeological interest that had been missed by other methods, such as elevation models, ground-penetrating radar, electrical resistance surveys, and others. It also uncovered the remains of structures and buried building foundations in areas where factors such as metallic contamination made other techniques difficult.

In 2023, members of the University of Tübingen in Tübingen, Germany, and the Tennessee Division of Archaeology in Nashville, Tennessee, published a protocol for using Dstretch to enhance imagery of tattoos preserved on mummified human remains.

Given how well it worked on his own extensive collection of rock art imagery, Harman said he was not surprised that Dstretch found wide use in the rock art community. “But I’ve been surprised by a lot of the different applications people have found. So that’s been cool.”

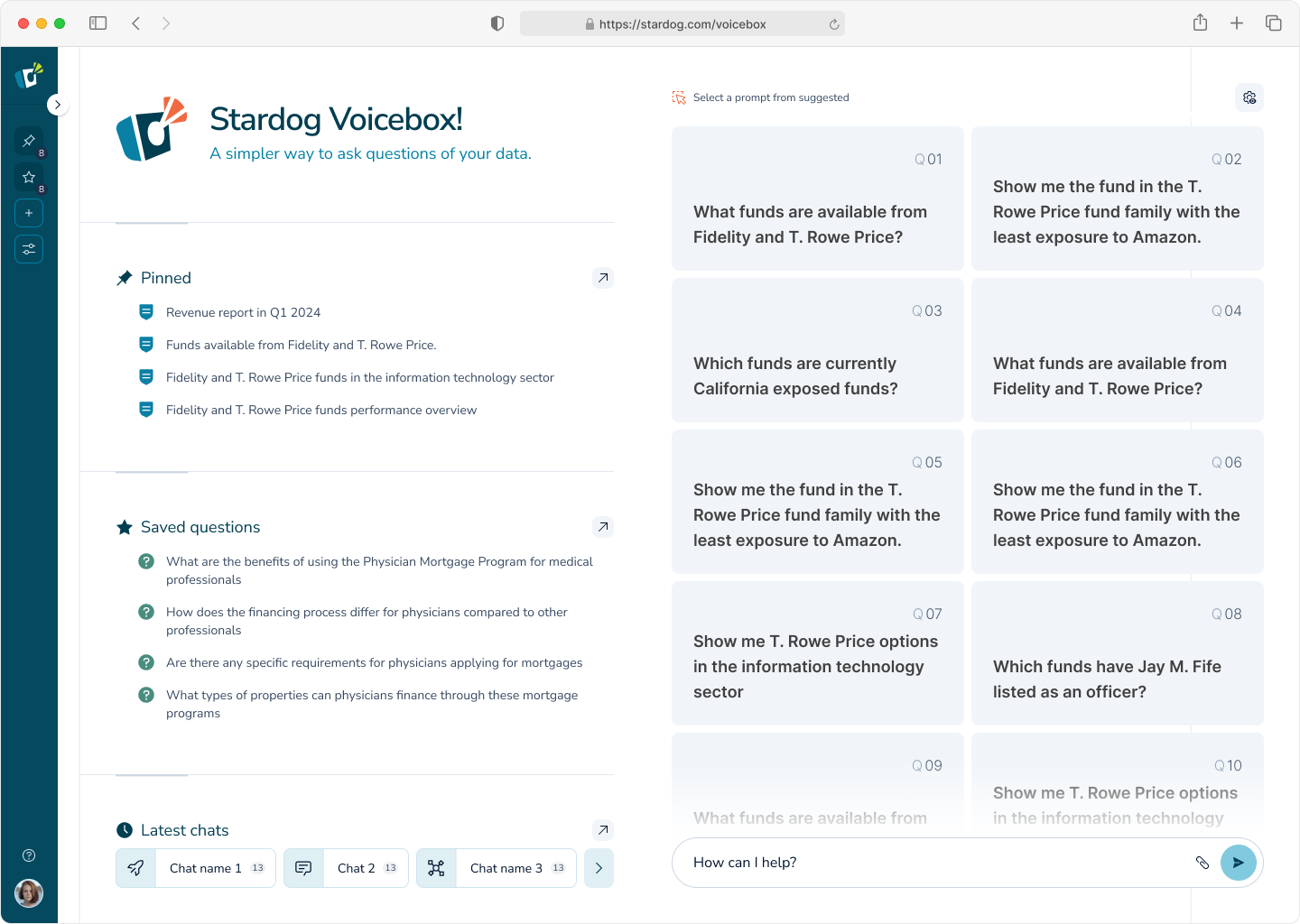

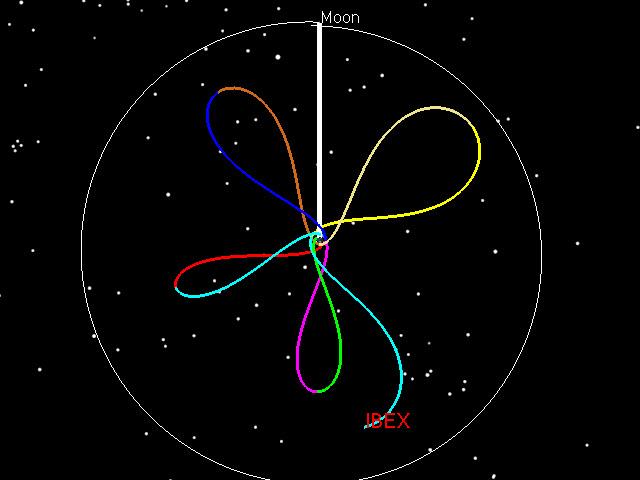

In 2005, someone at a rock art conference showed Jon Harman this image of the Martian surface, with and without the decorrelation stretch technique applied. Recognizing the potential value for discovering ancient rock art, Harman found a NASA paper detailing the method and created the Dstretch plug-in for use with an open-source image processing program. Credit: NASA

As he was developing the Dstretch plug-in, Harman applied it to this image from the Cave of San Borjitas in Baja California, Mexico. When the yellow figure appeared in the middle of the picture, he knew he had something useful. Credit: Jon Harman

Harman poses in front of an example of the Rancho Bernardo style of Native American artwork that’s barely visible until Dstretch is applied. Credit: Jon Harman

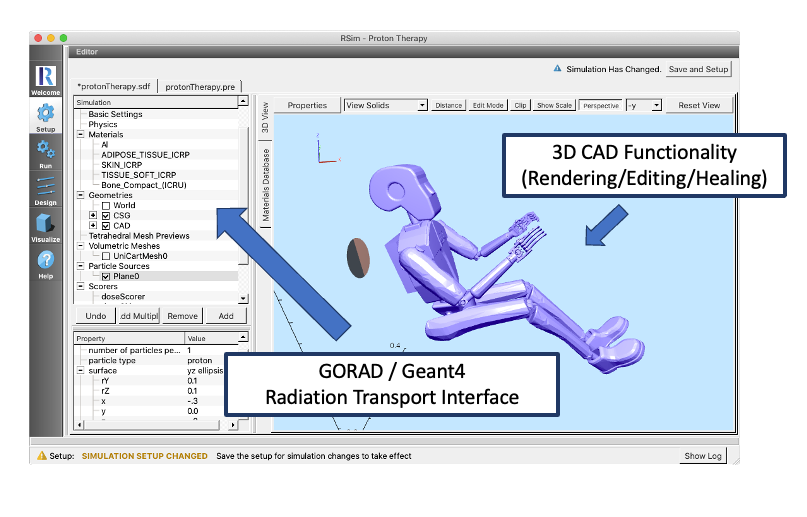

Between 2010 and 2012, Singaporean archaeologist Noel Hidalgo Tan used the Dstretch plug-in to discover more than 200 faded paintings around the Angkor Wat temple complex in Cambodia. Almost invisible to the naked eye (left), this image in a chamber near the top of the temple’s central tower depicts a traditional Cambodian musical ensemble known as a pinpeat. Credit: Noel Hidalgo Tan