Forecasting Fish from Space

Subheadline

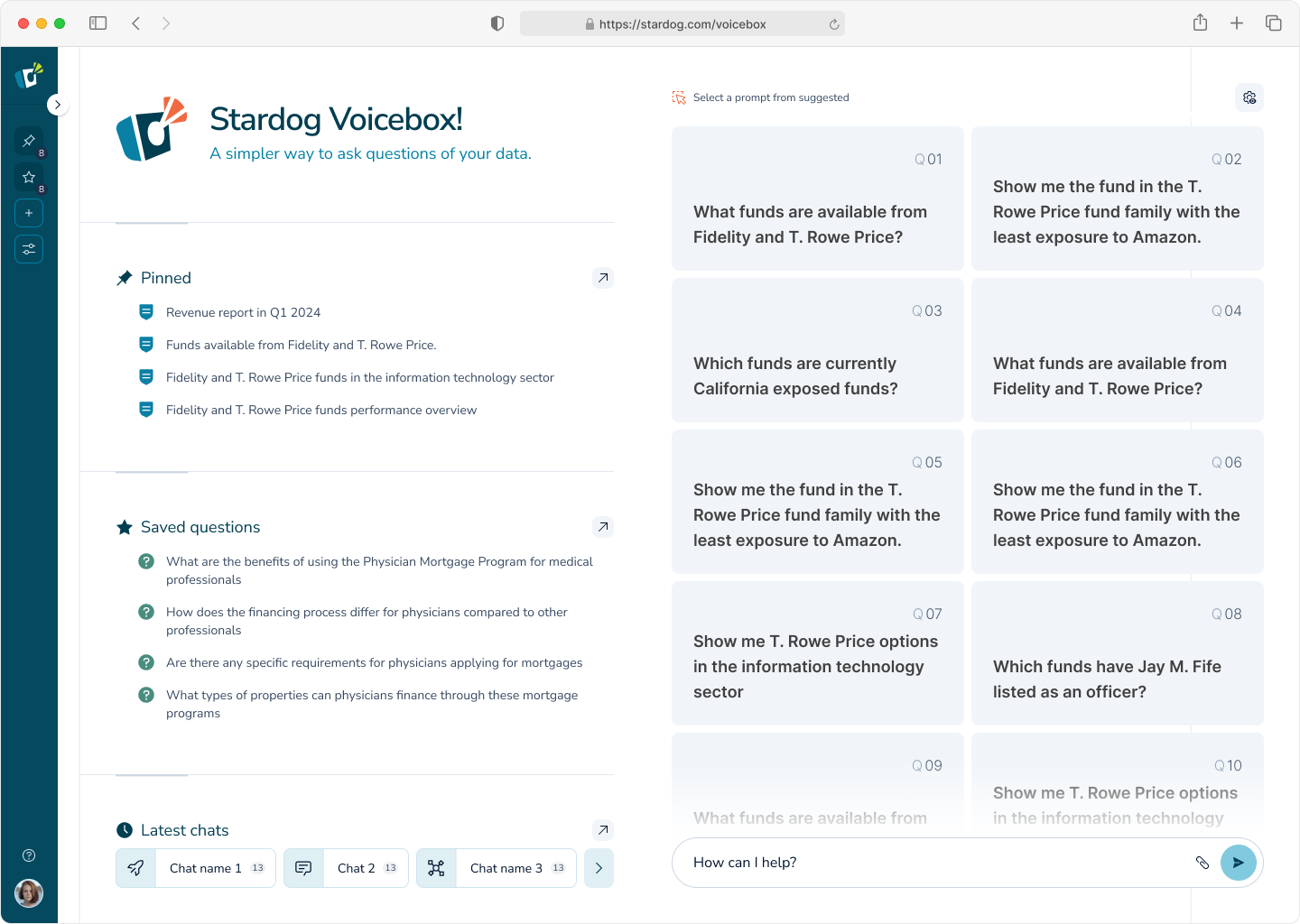

For four decades, company has used satellite data to guide sportfishing

Data from Earth-observing satellites is nothing if not versatile. Among other uses, these eyes in the sky help us look into the future to predict everything from the weather to worldwide crop yields to the behavior of sea ice. And for close to 40 years, satellite data has allowed one company to monitor and predict the movements and concentrations of game fish for sportfishing.

In fact, in the early 1980s, NASA helped pioneer the concept, carrying out the two-year Fisheries Demonstration Program with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other partners. They demonstrated that information on sea surface temperatures, combined with other data, particularly science-grade ocean color data — at the time from NASA’s Nimbus 7 oceanographic and meteorological satellite — could support five-day forecasts that improved anglers’ success rates.

In 1987, oceanographer Mitchell Roffer founded Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service Inc. (ROFFS) (Spinoff 1988), using satellite data to provide real-time estimates of the preferred habitat locations and bait concentrations for marlin, tuna, sailfish, swordfish, and other game species, as well as both short-term and seasonal forecasts of their movements. He also made customized forecasts for boat racers and the shipping industry.

Today ROFFS has grown to a 10-person team led by owner and President Matt Upton, a longtime employee until he bought the company from Roffer in 2018. A lot has changed for the West Melbourne, Florida-based business since it was founded, especially the technology. Whereas Roffer, in the early days, hand-drew his indications on printed maps and distributed them largely by fax machine, the company’s products today are all digital.

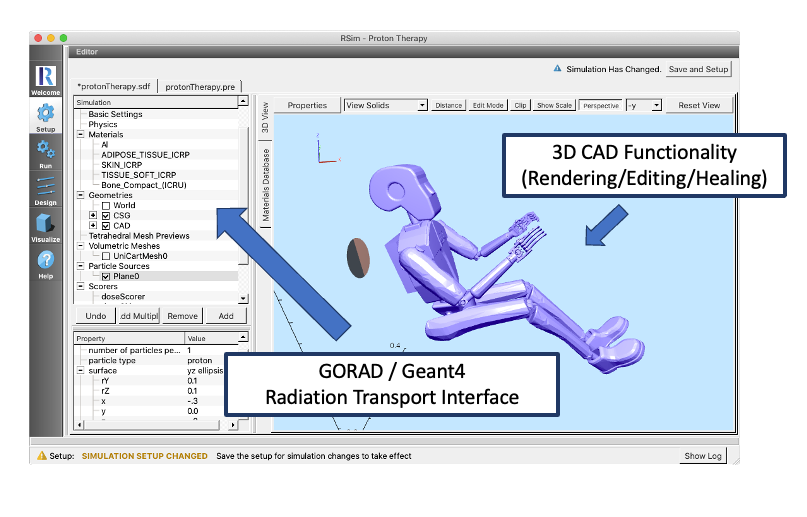

And ROFFS had to rely entirely on sea surface temperature data in its early years. The Coastal Zone Color Scanner on Nimbus-7 died the year before the company was founded, and the next ocean color-observing instrument didn’t launch until 1997. By the early 2000s, there were enough instruments in space to start relying on ocean color data. Today there are a host of sophisticated instruments observing the oceans from orbit.

Both color and temperature data can reveal frontal boundaries where two distinct water masses meet. These fronts “provide convergence zones for life — phytoplankton, zooplankton, then bait fish that feed on them, and then that’s where you find these larger pelagic fish that we help our clients find, like marlin, tuna, wahoo, dolphin fish,” said Upton. “They’re going to be where bait is.”

Water clarity can also affect the presence of some game fish, and knowing the ocean bottom structure and topography is important too, he said. Depending on the currents, large structures like ledges, canyons, reefs, and even shipwrecks can cause upwellings that carry nutrients to the surface, allowing phytoplankton — microscopic plant-like organisms — to flourish.

Collecting Oceans of Data

One of the main sources of data ROFFS relies on now is the Ocean Biology Distributed Active Archive Center (OB.DAAC) at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The archive, which was created in 2004, continually pulls in global ocean color and surface temperature data from several Earth-observing satellites.

“We get all this data, and we make it available to the public for whatever use they want,” said Sean Bailey, the oceanographer who manages OB.DAAC at Goddard. “Primarily, our focus is on scientists, but we do support these commercial communities as well.”

Some of the data comes from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, which launched in 1999 and 2002, respectively. The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instruments aboard the three satellites in the Joint Polar Satellite System, a joint NASA, NOAA, and Air Force program intended as a follow-up to MODIS, are major contributors. And the center incorporates data from the Ocean and Land Color Instruments on two of ESA’s (European Space Agency) Earth-observing Sentinel satellites.

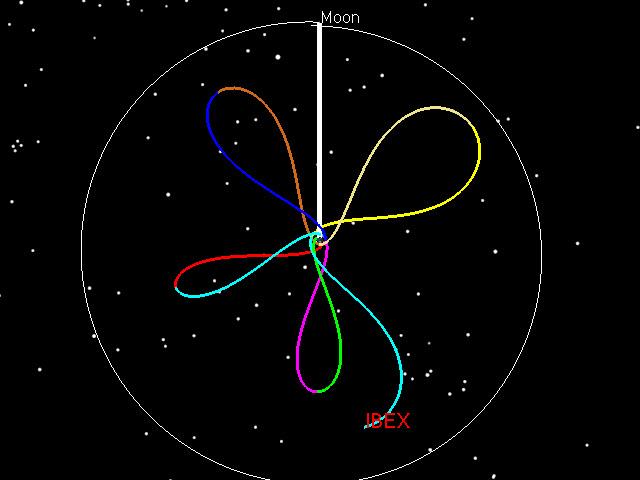

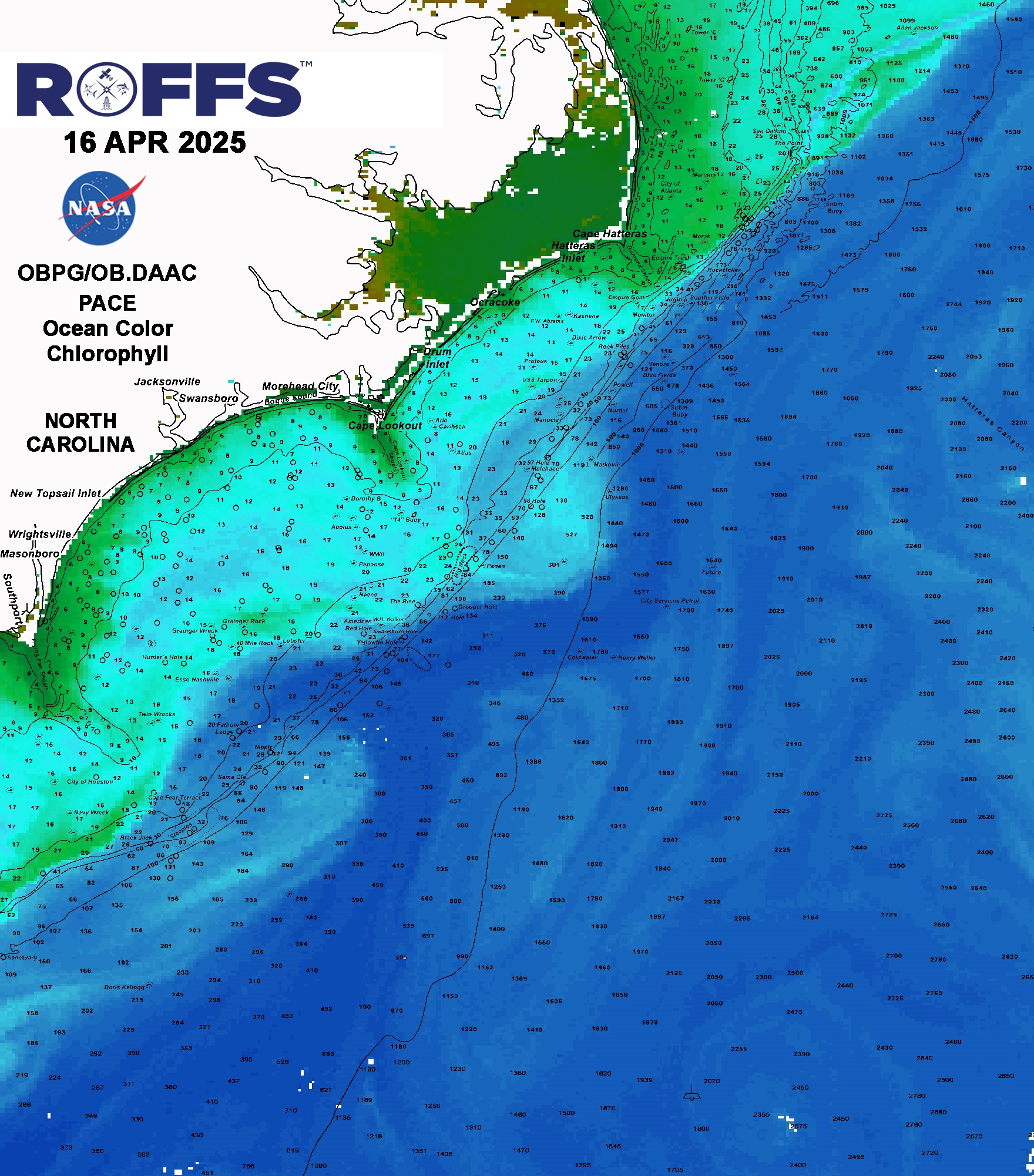

Recently, ocean observers got a more refined tool when data from the new Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem (PACE) mission became public. Whereas the MODIS instruments gather data in 36 spectral bands, and VIIRS in 22, the Ocean Color Instrument on PACE operates in 286 very narrow bands of wavelengths.

Ocean color is important to ROFFS mainly because it helps identify and verify frontal boundaries that tend to concentrate life, and it also can show the presence of chlorophyll, which indicates phytoplankton, the foundation of the marine food chain. PACE has such high spectral resolution that it can both detect the presence and concentration of phytoplankton and also differentiate between classes and species of them, Bailey said.

“It’s nice and crisp and seems to be accurate,” Upton said a few months after the company began working PACE data into its products. He also noted that data from the aging MODIS instruments has become less reliable with time. “So the introduction of PACE has really helped us out in the past few months.”

Free Data Drives Economic Ecosystem

Bailey said ROFFS is one of about 1,500 entities and individuals around the world that use OB.DAAC’s free subscription service. “Any user can say, ‘I’m interested in this part of the ocean, so I would like you to save a copy of the data for that region and send it to me,’” he said. “So every time a satellite goes over the region of interest, the data are extracted and staged for the user to grab from us.”

ROFFS then applies its own knowledge and in-house processing to the data to create its customized products.

Upton said predicting game fish locations for sports and recreational fishing makes up about 80 percent of the company’s business. Most of that activity is on the East Coast from Massachusetts to the Bahamas and from Florida to Mexico. The company also supports fishing tournaments around Bermuda and Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. Upton estimated ROFFS has about 2,500 regular users in the United States.

“It’ll blow your mind how much of the economy, especially on the East Coast, in the Gulf, and really anywhere, how many resources and jobs fishing brings,” he said. “Even big fishing tournaments draw crowds and boost the local economy, everyone from boat builders to restaurants.”

But predicting fish involves monitoring and predicting currents, and there’s a market for that information too. Oil and gas companies need to monitor and foresee ocean conditions around their offshore rigs to manage underwater operations, and ROFFS also occasionally helps them find favorable currents for ship routing when they move a platform to a new location.

The company has also helped the government and universities identify bluefin tuna spawning waters, track contaminated runoff plumes after hurricanes, and monitor oil spills.

Upton noted that ROFFS is one of many entities that depend on Earth-observation data from satellites. “It’s important to researchers, it’s important to industry, probably more than people know,” he said. “There are other companies like mine, and they rely on these satellites also. It’s free data, and we want to keep it free and keep the data flowing and improving, and NASA does a great job at that. That’s important.”

Bailey said the advent of PACE and its ability to identify types of algae will allow new products. Already the high-resolution Sentinel instruments have enabled a system warning of toxic cyanobacteria in inland waters. “The spacecraft wasn’t put up there to do that, but because we are measuring a variable that can be turned into a product, that can be used to support human health,” he said. “These are the kind of things that come out of the science that we do. So it’s important to look at Earth. We live here. We want to know what’s going on and how best to plan for the future.”

Ocean color data from NASA’s new Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem (PACE) satellite, shown here for an area along the shores of North and South Carolina, now helps Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service (ROFFS) predict where algae will draw the small fish that bring in the big fish anglers like to pursue. Credit: Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service Inc.

The PACE Observatory rests inside the Space Environment Simulator thermal vacuuum chamber at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center before undergoing thermal environmental testing in June of 2023. Following its launch in early 2024, PACE became a valuable source of data for fishing predictions from ROFFS. Credit: NASA

Big game fishing is more fun where the big fish are. ROFFS combines data from Earth-observation satellites with its own proprietary methods to predict where anglers will most likely find fish like marlin, tuna, swordfish, wahoo, and the mahi-mahi seen here. Credit: Getty Images

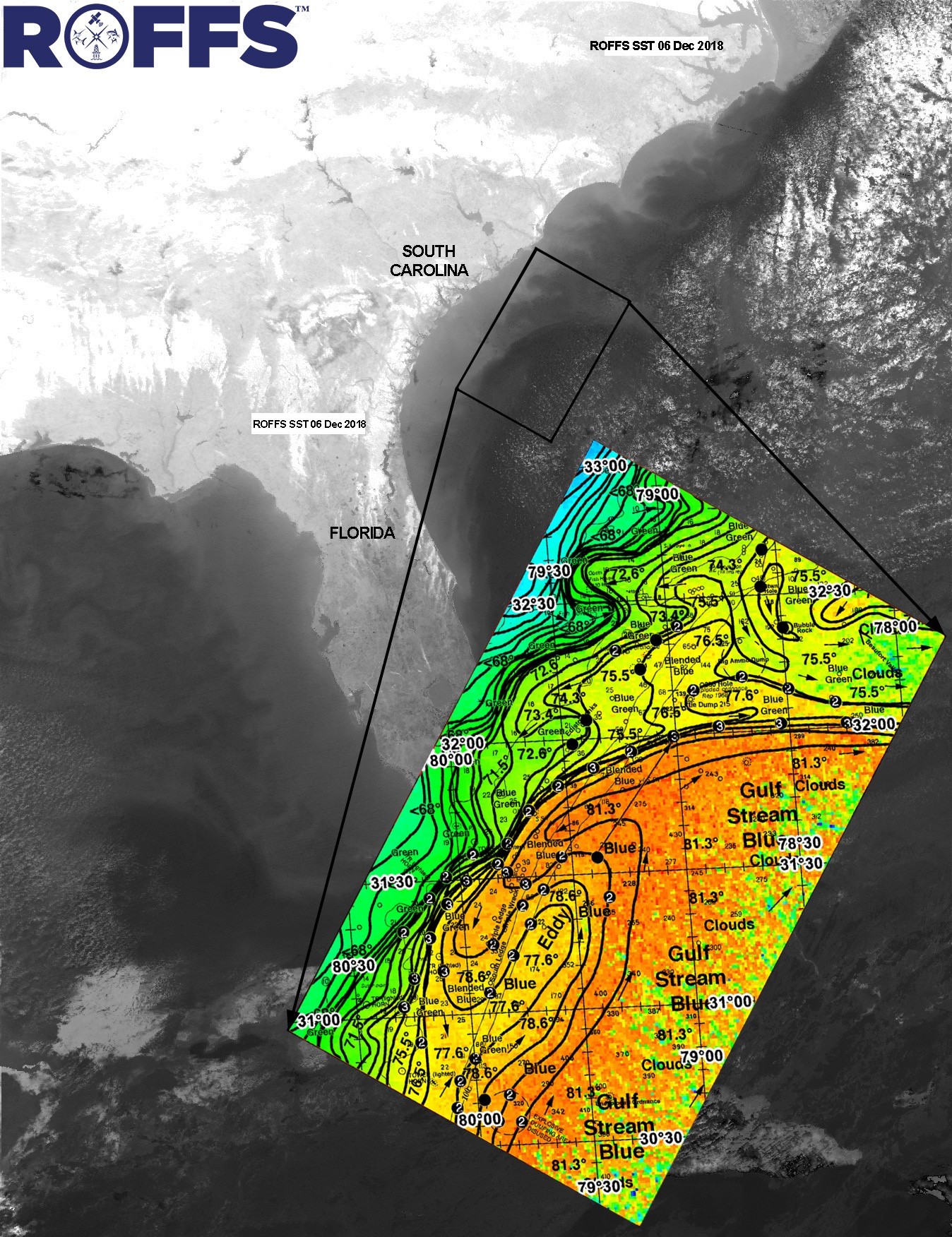

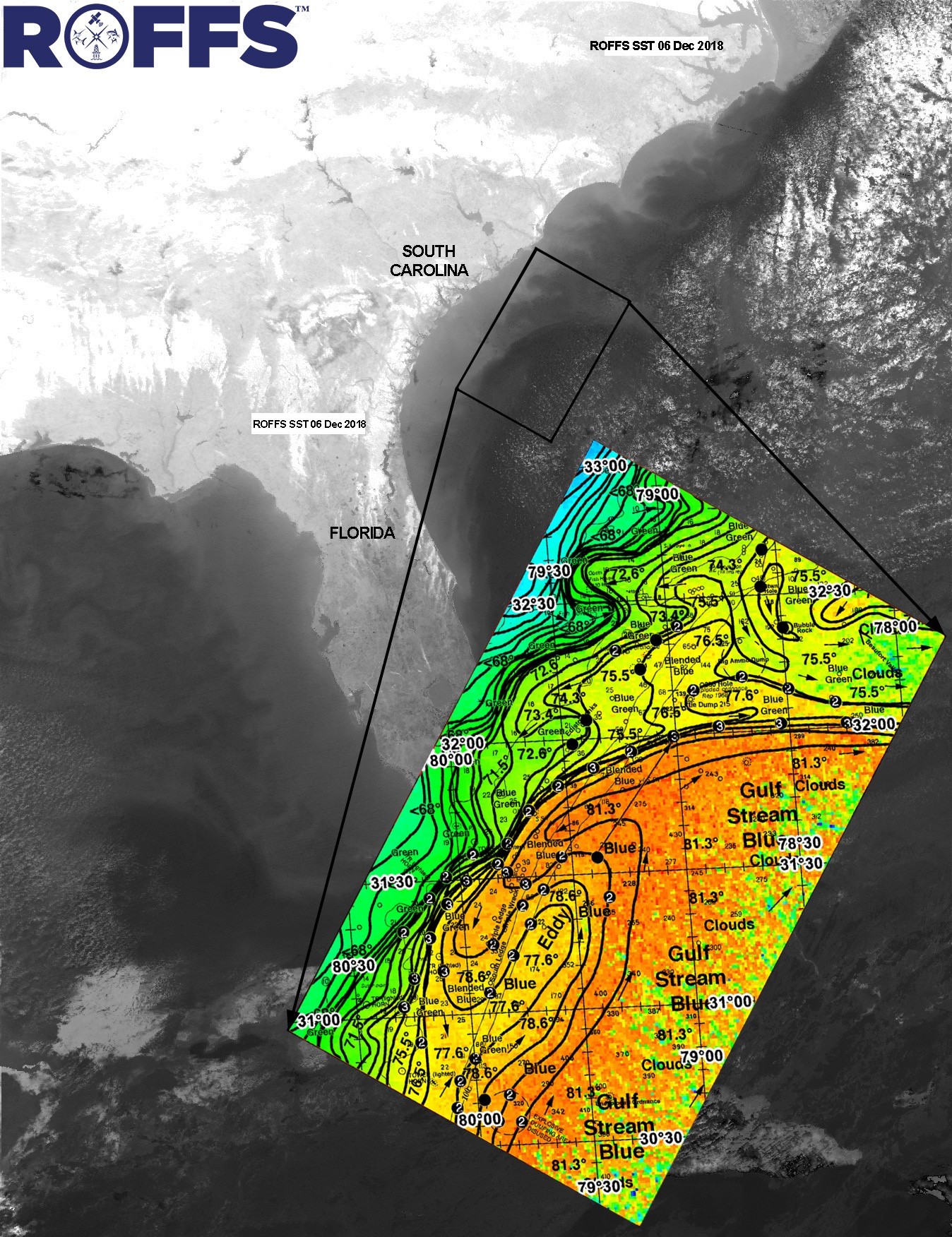

This example shows a forecast from ROFFS for the presence of big game fish in an area off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia. Credit: Roffer’s Ocean Fishing Forecasting Service Inc.